Lisa Willemse and Catherine Anderson, Communication, Education & Outreach co-editors

In our last editorial, we discussed a report by the Council of Canadian Academies that labeled science culture as “underdeveloped” in English Canada. This gap appears to be rich in opportunity for Canadian science bloggers and other creators of science communications. But those of us who do this sort of work know that it’s not quite as simple as penning a few words or taking a few photos and posting them, so we created a survey to better understand how science content is being produced in this country.

Our survey asked several questions, including how respondents produce content, how they share it, and whether they do this a part of a paid job or on a volunteer basis. We also wanted to know what forms of content production they’d like to try and what might be holding them back. We had 54 responses: clearly not representative of the number we know are engaged in this work, but enough for us to get a sense of the community and to identify some trends. Forty-three of our respondents were from Canada, seven from the US, and four from Europe or the UK.

While we can’t unpack all the data in this single blog post, we want to highlight some of the results we found most interesting. We hope to include other results in future posts.

Where we consume science content

Our first question was intended to get a sense of where our community receives or consumes science content, with multiple answers possible. A total of 201 answers indicate that, on average, people seek information from three to four different sources, with only 13 respondents using one or two different sources. Not surprisingly, the responses were heavily skewed towards online content, a bias that reflects the fact that the survey was primarily circulated online and thus would likely only attract responses from those who visit the blogs and feeds where it was posted. Nevertheless, nearly 60% said they do consume content via traditional media, such as newspapers, magazines, radio, and television. Oral communications was also popular, with 50% citing public talks and 54% using the academic setting (lectures, literature) as information sources. Overall, half of peoples’ science content is obtained online, perhaps more if one considers that most traditional media (newspapers and magazines, for example) are available online.

How we identify ourselves as producers of science content

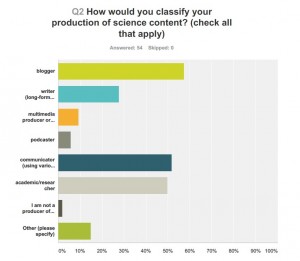

We wanted to get a sense of the kind of work or activities people were involved in that contributes to the production of science content. Our respondents self-identified the categories that best represented them, with 118 selections made. Fifteen respondents only identified a single method of production, and one respondent indicated he/she was not a producer at all. Interestingly, of those who identified only one method of production, nine identified as academic/researcher. The rest of us (38) wear many hats, and on average identify 2.68 different methods of content production as part of their contribution. The breakdown can be seen below.

We want to do more production, but…

We want to do more production, but…

Our survey respondents showed a great deal of enthusiasm for content production; hardly surprising, given that this is the community we were targeting and that all but one indicated that they currently produce content of some form. All but nine said they had an interest in trying new forms of content production, and the list of areas of interest ranged greatly, from creating online story maps to video production to writing a novel. Blogging and long-form writing predominated the comment list. Of the nine who did not wish to do more production, six were already engaged in three to four activities, while the other three were academics, presumably with no time to pursue content production.

We also identified a noteworthy trend in respondents’ areas of interest. Those that aren’t blogging listed blogs as something they’d like to try, but those that are blogging are still looking for new ways to produce science content. It may be that blogging is the gateway drug that introduces you to the many other wonderful opportunities to get involved in science communication. Writing is still an interest, but podcasts, art, and video were also identified as intriguing to our content producers.

In terms of why we might not be trying these new forms of science content production, the survey responses show clearly that the number one reason is the lack of time. The second reason is not having resources – either the training and/or the confidence, or the money to support the endeavour.

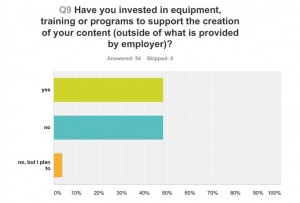

More than half the respondents had or plan to make a financial investment in science communications of their own volition, which further supports the interpretation that there is a great deal of enthusiasm in this community.

As for the kinds of investments made, they ranged from relatively small (i.e., podcasting microphone or books) to large (training courses, camera equipment and software).

As for the kinds of investments made, they ranged from relatively small (i.e., podcasting microphone or books) to large (training courses, camera equipment and software).

Volunteer vs. paid work

Despite people saying that they don’t have enough time, many hours per week are dedicated to producing science content. For the 44 people who indicated they produce content as part of a paid job, the distribution weighed slightly in favour (24 people) of those doing it as a small part (less than 15 hours per week) of their career. Of this group, 16 identified as academics/researchers, which seems appropriate given the job profile. The balance of respondents who are paid to produce content (20) spend more than 15 hours per week in this capacity.

What really stood out to us was the volunteer work. Even considering the small sample size, if we take the average of the ranges of the volunteer time, we still get a very large number — 230 hours per week! From just the 35 people who indicated they do volunteer work, they spend an astonishing 12,000 hours (approximate) per year in volunteer time producing science content. Simply incredible.

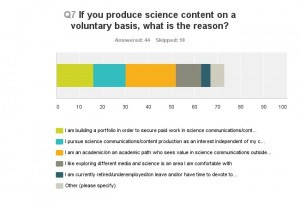

Why would the community engage so heavily in volunteer science content production? The chart below shows a balance between those who desire a career in science communications, a love of the field, and academic interests.

In sum, the data we collected, while limited, highlights a committed and energetic community of Canadian science content producers, one that we suspect is largely overlooked in reports on science and science culture. This community has just begun to organize into the kind of structures that could have greater impact in the sharing of scientific findings and higher profile of science pursuits in Canada.

In sum, the data we collected, while limited, highlights a committed and energetic community of Canadian science content producers, one that we suspect is largely overlooked in reports on science and science culture. This community has just begun to organize into the kind of structures that could have greater impact in the sharing of scientific findings and higher profile of science pursuits in Canada.

One thought on “How we do science communication: survey results”

Comments are closed.