Lené Gary, General Science co-editor

When life is leaping forth in its freshest tender green and shrubs are casting best their wine-rich blooms of color, there comes a humming. Not just from the song of spring rising in the world, but wing beats – fifty-two to sixty-two per second.

From now through May, rufous hummingbirds will be arriving in the Fraser Valley, British Columbia, where they will briefly court, nest, and raise their young before heading back to Mexico. They, like other hummingbirds, are avian pollinators, and they, like other pollinators, are in serious decline.

Between 1966 and 2014, the global population of rufous hummingbirds declined by 62 per cent.This year, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) added rufous hummingbirds to their Red List.

Dr. Christine Bishop, Research Scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), is working with colleagues to find out whether neonicotinoids (“neonics”), the class of insecticides often implicated in harming bees, may be negatively affecting hummingbirds as well, specifically rufous hummingbirds.

Even though insect and animal pollination is needed to produce 75 per cent of the world’s food crops, one of the most important avian pollinators – hummingbirds – has been largely overlooked in studies concerned with pollinator pesticide–exposure risk. In fact, Dr. Bishop’s work is the first to document hummingbird pesticide exposure.

When asked why this is, Dr. Bishop offered a couple of possibilities. She said that the technology needed to detect extremely small amounts of pesticides has only existed for one to two decades. In addition, hummingbirds are nectarivores (primarily consumers of nectar), and pesticide exposure via nectar was not considered a significant route of exposure before the development of neonicotinoids in the 1990s. Neonics are water-soluble and act systemically, meaning they are taken up by the entire plant and are present in all the plant’s tissues, including its pollen and nectar.

While hummingbirds are known to consume nectar, there is reason to believe they may consume some pollen too. A fossil found in Messel, Germany, reveals that the earliest known bird pollinator had two types of pollen in its stomach.

Dr. Bishop first considered the question of whether pesticides might be a factor in the decline of rufous hummingbirds in 2014. She was on a spring walk near a park that borders blueberry fields and saw a large number of the birds performing their courtship display. She knew they would be nesting nearby and began to wonder if they were being exposed to the agrichemicals used in blueberry production.

She shared her thoughts with her collaborator, Alison J. Moran, a seasoned bird bander. Moran mentioned that when hummingbirds are banded, they often urinate. Moran wondered if they could collect hummingbird excretions and measure the birds’ exposure to pesticides through them. That fruitful conversation led to what has become a multi-year study.

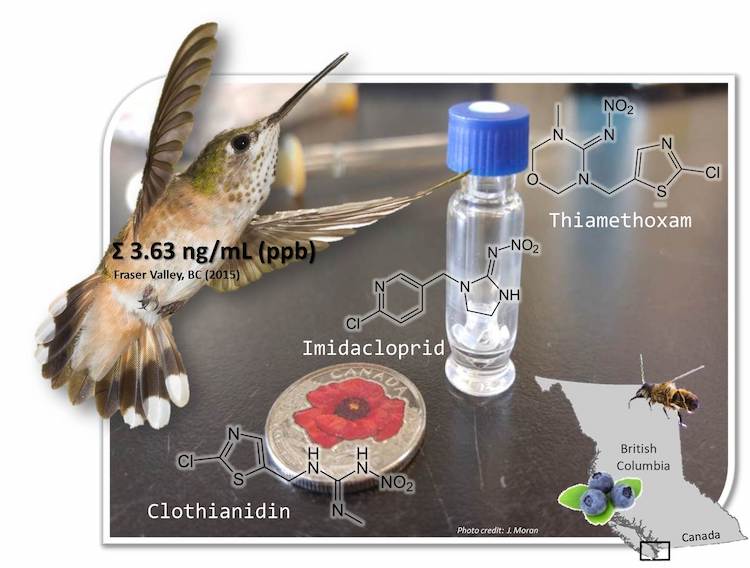

In the first two years of their study, they detected three neonicotinoid insecticides in rufous and Anna’s hummingbird urine – imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin. They also collected bumblebees and their pollen, and blueberry leaves and flowers to test for pesticides.

In one of six blueberry flower samples, they detected imidacloprid even a year after its application. This means that hummingbirds could be exposed to imidacloprid from a flower that was not directly sprayed with pesticides.

Because pesticide exposure in hummingbirds has never been studied before, researchers can only speculate about the potential health effects of these exposures, based on studies of other species.

One recent study showed that songbirds consuming just four imidacloprid-treated canola seeds lost their appetite and weight, had migration delays, and had trouble orienting during migration. These sub-lethal effects increase the risk of mortality and potentially compromise their opportunities for breeding.

Hummingbirds don’t eat seeds like the songbirds, but treated seeds pose secondary problems. A slide from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Corn Dust Research Consortium reads: “The Current Issue is not the Plant but the Planting.” This declaration is followed by a description of one seed-related problem – contaminated dust:

Problems for pollinators are created when this dust settles on nearby plants that they depend on for forage.

In Ontario, nearly 100 per cent of the corn seed and 60 per cent of the soybean seed sold are treated with neonicotinoid insecticides, but they’ve made significant changes in the planting procedure to ameliorate the contaminated dust problem. Since 2014, the government has required that farmers integrate a seed-flow lubricant when planting neonic-treated seeds.

And it’s working. According to Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA), during 2014–2017, the bee incident reports dropped by between 70 and 92 per cent.

Another treated-seed related problem is leaching. Research suggests that neonics applied to seeds leach into the surrounding soil where they are then taken up by wildflowers growing in the margins. The pollen of those wildflowers is as contaminated as the pollen of the crop grown from treated seed – sometimes even more contaminated.

PMRA is working on other ways to reduce neonicotinoid related risks. In the summer of 2018, they proposed a ban on clothianidin and thiamethoxam. If the ban takes effect, it will likely have a 3- to 5-year phase-out. The fate of imidacloprid is still up in the air. The final decision to ban the compound has been postponed from December 2018 to December 2019.

In the meantime, you can help make a safer home for all pollinators by planting native plants purchased from nurseries that don’t use neonics, avoiding pesticide use around your home, and purchasing food grown without pesticides, as migrating birds often follow the valleys where agriculture is prominent.

Whether you’re admiring them from afar or feeding them year-round, hummingbirds are not only a delight for the soul, they’re essential. They are prized pollinators pulsing with life.

When I asked Dr. Bishop what it feels like to hold a hummingbird, she said, “I’ve held a lot of wildlife in my life.” My heart sank, as I’d hoped she would express something as magical as I had imagined, but then she continued, “It feels like vibrating energy in your hand. You have to respect that and be awed by it.”

Dr. Bishop then reminded me that these tiny birds travel thousands of miles, sometimes migrating from Canada to Mexico and back more than once in their lifetime.

Yes, respect and awe, I thought. Absolutely.

~30~