Robert Gooding-Townsend, Science in Society co-editor

Today, I’m at the airport, heading back from a visit to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston, where I enjoyed a series of scientific talks. Exciting, right? Except, I wasn’t attending a conference, presenting anything or meeting any potential co-authors. In fact, nobody seemed to take me seriously at all. So what do I have to be excited about?

Well, this lecture series was different. It was the Festival of Bad Ad Hoc Hypotheses, commonly known as BAHFest. Entrants were not competing for citations but for chuckles by spinning wild theories from well-established facts. Past topics have included the benefits of halting terrestrial revolution, mammalian sleep as an adaptation for evolutionary dread, and yawning as an adaption to consume insect protein. With tongue planted firmly in cheek, these presentations show the fun side of science – and subtly make some more serious points.

BAHFest is hardly alone in making jokes based on science. The small and intensely nerdy field of science comedy has been around in various forms for decades. Not only are these a lot of fun (for those of a certain mindset, at least) but they can advance science in a surprising number of ways.

You may have encountered science humour, reluctantly, in high school classrooms:

A neutron walks into a bar and asks the barman, “How much for a drink?” The bartender says, “For you, no charge.”

Helium walks into a bar. The bartender says, “Sorry, we don’t serve noble gases.” Helium doesn’t react.

Fuzzy Wuzzy was a chemist.

Fuzzy Wuzzy is no more.

For what Fuzzy thought was H2O

Was H2SO4.

Why aren’t there any good chemistry jokes left? All the good ones argon.

These pithy jokes (and many more like them) have been recycled for years. Or as folklorists would say, “Science has a rich oral tradition.” Technical humour isn’t confined to the hard sciences but can be found across all academic disciplines from linguistics to computer science to music theory. And it’s far from static – people are making up new jokes all the time: among friends; in classrooms; and especially on social media.

A: Your greatest weakness?

B: Interpreting semantics of a question but ignoring the pragmatics

A: Could you give an example?

B: Yes, I could— Gary "鯨ç†" Illyes (@methode) August 24, 2016

A programmer’s visual pun. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature. (source)

Sly jokes can show up in more formal contexts, such as titles, footnotes, and acronyms in published papers. Still, standalone jokes have their limitations. They tend to be one-offs, with little by way of creative context, follow-up or any real point to make. And a lot of them are puns, which can produce more groans than grins.

A woman in liquor production

Has a still of exquisite construction.

The alcohol boils

Through magnetized coils.

She says, “it’s called proof by induction.”

Fortunately, science humour isn’t limited to one-off quips. There are venerable institutions, too, such as parody journals and the 27-year-old Ig Nobel prizes. The Igs, as they are known, are awarded to findings that are ridiculous but true: dung beetles navigating by the Milky Way; rats’ inability to distinguish English from Japanese when played backwards; and the Belarussian president and police force for, respectively, making it illegal to applaud in public, and arresting a one-armed man for doing so. In 2016, a team of Canadian psychologists won the Peace Prize for their study “On the Reception and Detection of Pseudo-Profound Bullshit”.

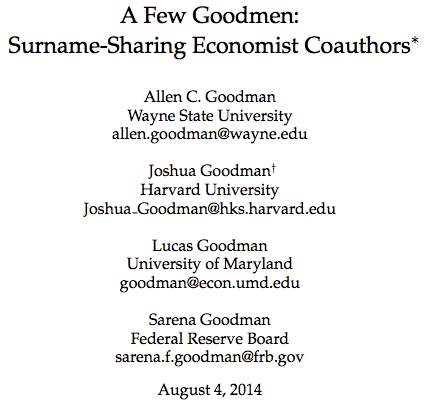

Four economists with the same name collaborated to write a paper about collaborations of economists with the same name. (source)

Special relativity, by Science Borealis’ Raymond Nakamura. Available on various objects!

There are also comics, parody songs, and other outlets. Science-based cartoons can often be found on professors’ office doors, either as newspaper clippings or as webcomics. Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, xkcd, and PhD Comics are some of the best-known, although there are plenty of others, such as informative nature comics at Bird and Moon or Science Borealis’ own Raymond Nakamura. Funny science songs include Tom Lehrer’s classics, Tim Minchin’s statistically literate love song, and Canadian contributions such as A Capella Science’s lyrically dense Bohemian Gravity and last year’s Generator with the ever-popular Chris Hadfield.

Now, what’s the point of all this? Do these shenanigans deserve any attention, or should we get on with the real work of science?

Actually, science humour accomplishes quite a lot. Much of this depends on context. In a classroom, jokes can be good teaching aids since to get the joke you have to understand the underlying content. And if it’s funny, it even serves as a reward! From another angle, jokes can help struggling academics and students feel less alone or make the best of a tough situation. The full title of PhD comics says it all: Piled Higher and Deeper. In addition to providing support, humour can spur creativity through absurdity.

For scientists, [humour] can be a new way to develop presentation skills and reach audiences.

The official purpose of the Ig Nobels is to recognize research that “first makes people laugh, and then makes them think”. The annual Ig Nobel ceremony is not only a social event showing the wacky, wonderful possibilities of science, but occasionally a launching pad for findings that gain broader recognition, such as the Dunning-Kruger effect. BAHFest originated as parody of flimsy narratives in evolutionary psychology, and shows how easy they are to make up – making critical thinking much more fun than it normally is.

All humour, in any context, celebrates creativity, which can be lacking in competitive scientific environments. Science humour can create shared references and a feeling of belonging, especially for people who may not enjoy standard comedy. For scientists, it can be a new way to develop presentation skills and reach audiences. It can also challenge entrenched norms: through comedy, younger and less established researchers, or even non-scientists, can talk about “big questions” in a way that is rarely so accessible elsewhere.

This is not to say that science humour is always positive. Beyond the undeniable fact that many people simply don’t enjoy it, it can sometimes be harmful to science. This is the flip side of increasing accessibility: humour isn’t peer reviewed, and can easily be taken out of context – say, into policy debates. There is a risk of presenting an oversimplified or even fabricated account for the sake of laughs, especially in the context of discrediting a certain point of view. And satire can easily turn mean: for example, the longstanding “Dihydrogen monoxide awareness campaign”, which parodies overhyped fears of chemicals, often ends up smugly mocking ignorance rather than educating, undermining its message and potentially turning people off science.

Science comedy is like basic research: we do it because it’s fun and interesting, and sometimes it happens to produce useful results. As scientists both organize politically and combat online misinformation, it’s worth remembering that humour is part of our toolbox. Like any tool, science humour can be misused, but, like a good Swiss Army knife, it’s amazing how useful it can be.

Robert Gooding-Townsend was the winner of BAHFest East 2015, and a judge of BAHFest East 2017.

*Header Image: Zach Weinersmith, creator of BAHFest, presenting his famous “Infantapulting hypothesis” that started it all. (CC).