Jenna Finley, Biology and Life Sciences co-editor

Since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve all been aware that exhibiting symptoms is not an equal opportunity game. Some people don’t even know they have the COVID-19 virus, while others are fighting for their lives in intensive care units.

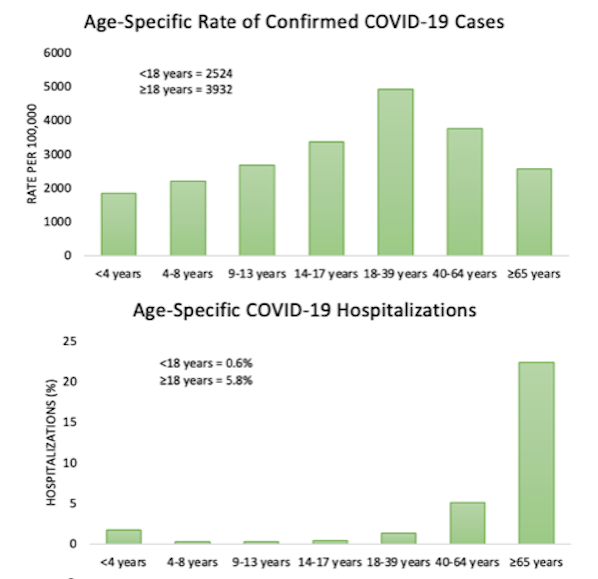

One group that is more likely to be asymptomatic is children. A University of Alberta study found that over one-third of children with COVID-19 show no symptoms, while other estimates put the number as high as 79 per cent. Compare that with an Ontario study finding that 6.8–15.2 per cent of adults between 20 and 80 years old are asymptomatic, and you might start wondering why there is such a disparity. The surprising answer could be those pesky childhood illnesses, some of which are seasonal coronaviruses.

These graphs show the rate of infection with COVID-19 per 100,000 (top) and the percent of cases that resulted in hospitalizations (bottom) by age group in Ontario between January 15, 2020, and June 30, 2021. Graphs by the author based on Public Health Ontario’s Epidemiological Study data, CC0

Seasonal coronaviruses

Before the pandemic, most of us probably hadn’t heard much, if anything, about coronaviruses. As it turns out, there are hundreds of types of coronavirus, with four being especially common in humans: 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1.

Usually, a coronavirus infection isn’t a big deal. The symptoms for the most common human coronaviruses are so mild that they don’t warrant a trip to the doctor, are nearly indistinguishable from the common cold and tend to stick to the upper respiratory tract. In fact, they account for about one-quarter of suspected colds.

The coronaviruses we have to worry about are the novel ones. These coronaviruses made the jump from animals to people. You’ve probably already heard of them: SARS, MERS, and COVID-19. The first two are much more likely to infect the lungs than the upper respiratory tract, while COVID-19 can get a foothold in both, making it more transmissible and deadly.

So, that pesky cold that ran rampant through your child’s school recently? That could have been a coronavirus, and those kids might have it to thank for their apparent asymptomatic COVID-19 experience.

Memory immunity

How do previous coronavirus infections help us fight off new coronaviruses? It all comes back to something called memory immunity. Memory immunity develops after an infection and is a significant part of our adaptive immune response. The adaptive immune response is more specialized than the initial non-specific innate immune response in how it targets and destroys an invading pathogen.

The major players in our adaptive immune response are T-cells and B-cells. There are several different types of T-cells, including helper T-cells and cytotoxic T-cells. Helper T-cells activate the adaptive immune response, and cytotoxic T-cells destroy any infected cells. B-cells produce antibodies, which inactivate the pathogen or mark it so that other cells can recognize and destroy it.

After an infection is taken care of, most immune cells undergo programmed cell death, a process called apoptosis. They die because they have outlasted their usefulness. However, when these cells first divide, memory cells of each type are created alongside them – memory T-cells and memory B-cells.

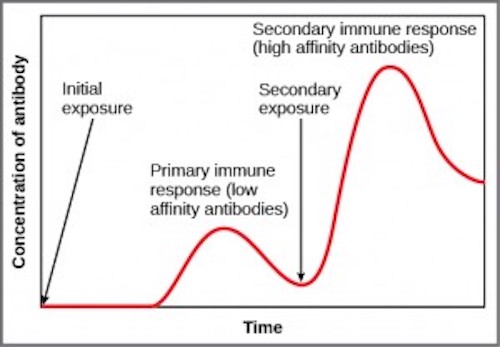

When memory immunity is activated by a re-occurring infection, B-cells produce a higher volume of antibodies with a very high affinity for the pathogen more quickly. Image from Concepts of Biology by Charles Molnar and Jane Gair, CC 4.0

These memory cells stick around long after the infection is over to protect you from reinfection. Because the adaptive immune system has learned how to fight this infection, it can mount a quicker and more effective response. The rapid response shortens the infection time and can even stop the pathogen before it becomes established, so you may never even know you were infected. This response explains why you don’t contract chickenpox twice and is the basis of vaccines.

This animated video by the Amoeba Sisters gives a deeper (and funnier) overview of some of these terms and concepts. (8:55 minutes).

Cross-reactive immunity

Why would our immune response to other coronaviruses help us with COVID-19? It turns out other human coronaviruses and COVID-19 might appear very similar to our immune system. When infected with COVID-19, our immune system can mount a response called cross-reactive immunity using memory cells produced after other human coronavirus infections. This response is more common in children, as they tend to get sick with coronaviruses more often. It may also play a significant role in adults who appear asymptomatic.

We all went through school and suffered those terrible colds, so why don’t adults show this memory response as frequently? Unfortunately, this immunity isn’t long-lasting. Memory immunity doesn’t always last your entire lifetime, and its persistence varies depending on the disease that triggers it. So, people who have been out of school for a while and get sick with coronaviruses less often may not have those immune responses anymore.

The official logo for Stop the Spread game. Image from Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0

School-aged children are more likely to have coronavirus memory cells circulating in their blood and lymph. However, parents and teachers cannot rely on this immunity because kids aren’t guaranteed to have it and can still spread the virus if they do.

With children now back in school, it is important to understand that an asymptomatic child does not mean an uninfected one. Make sure you and your kids wear a mask, wash your hands regularly, social distance, and stay safe!

~

Banner image: Our immune system has many components and protects us from a broad range of diseases. Image by EpicTop10.com, CC BY 2.0