Mary Anne Schoenhardt, Science in Society editor

You may know that the iPhone 12 Pro contains a lidar (light detection and ranging) sensor. A remote sensing technique originally developed for space exploration and military defence, lidar is more than just a fancy gadget for your new phone. One of the lesser-known uses of lidar is to uncover the past.

Archaeology is the study of historic and prehistoric humans through material artifacts. It provides us with a tangible connection to the past. One of the challenges of archaeology is that the remains left by ancient peoples are often no more than tiny imprints on the modern landscape. Lidar can be used as a tool to view landscapes in a way that the human eye can’t, helping to identify what our ancestors left behind.

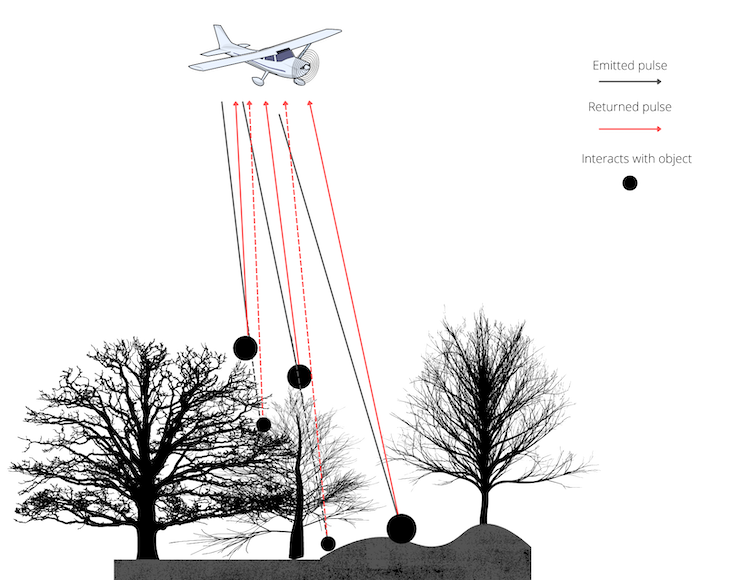

Lidar uses pulses of light to measure distance. These light pulses travel through the air until they hit an object and bounce back to a sensor. Using the speed of light and the time it takes the light pulse to return to the sensor, the distance between sensor and object is calculated.

Lidar sensors emit pulses of light, which bounce off features on the Earth’s surface and return to the sensor. As the light pulse travels from the sensor, it will diverge. This means it may interact with more than one surface and create multiple returns to the sensor (indicated by the dashed lines). When a sensor is carried by plane or satellite, lidar can be used to produce topographic views of a landscape. Image by Mary Anne Schoenhardt

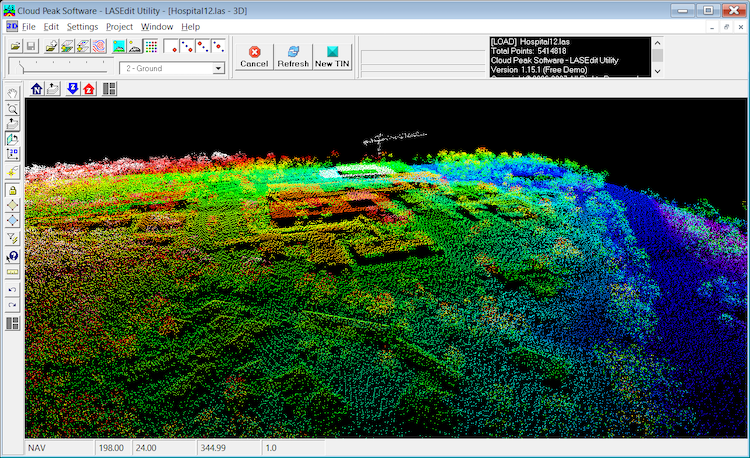

For large-scale data collection, lidar sensors are attached to planes or satellites. The sensor emits between 20 and 100,000 pulses per second and measures distance with subcentimetre accuracy. The data collected can be used to create incredibly detailed three-dimensional depictions of the Earth’s surface, called digital elevation models (DEMs).

Even at a fairly coarse resolution, points collected by a lidar scanner flown on a plane can be used to display the Earth’s surface. These points, showing a hospital campus, are colour-coded to represent change in elevation. There are groups of trees and a crane near the horizon and the hospital building is in the center of the image. The three-dimensional surface created by joining the data points is known as a digital elevation model (DEM). Image by Greg Wilson, LASEdit 3D View – Hospital Campus, CC0

Lidar models are extremely useful for identifying patterns or relationships not visible to the human eye – including archaeological sites, such as an eighteenth-century siege trench near the border of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Fort Beauséjour was built in 1751–1752 by the French to defend Acadia, their territory in North America. In 1755, it was lost to the British and renamed Fort Cumberland. The British used the fort to defend their North American territory during the American Revolution and the War of 1812. In the 1960s, archaeologists attempted to reconstruct it. Records showed that the British built a trench during the siege of 1755, but the rough terrain and dense vegetation of the region made it almost impossible to find.

Fort Beauséjour–Fort Cumberland National Historic Site, as it is today. The siege trench is located about 1 km north of the fort remains. Image by Shawn M. Kent, Fort Beauséjour–Fort Cumberland National Historic Site, Canadian Parks Service, CC-BY-SA 4.0

It was not until 2006, when a group from Parks Canada and Acadia University flew a lidar sensor over the area to identify archaeological features, that the trench was located. Flying the mission before spring leaf-out allowed a large number of lidar pulses to penetrate the forest canopy and reach the ground. Data processing removed the surface vegetation from the dataset and a DEM was created from the remaining information. An artificial illumination technique better defined surface features and revealed the linear pattern of the trench. The archaeologists found the exact location of the trench in the field using GPS. In many places, the trench was no more than a 20-cm ditch and could easily have been overlooked without the precise location provided by the lidar image.

Lidar data can be used to go even further back in time. Many scientists believe that people first arrived in North America on the northwest coast during the late Pleistocene (12,000–13,000 years ago). But changes in sea level, post-glacial activity, and dense vegetation cover in the region make it difficult to identify potential archaeological sites. In Canada, most of the known sites are on the islands of Haida Gwaii off the coast of British Columbia, but archaeologists believe there may be many other sites along the western coast of North America.

A research group from the Hakai Institute, the University of Victoria, and Arizona State University used lidar to identify regions of high archaeological potential on Quadra Island, located south of Haida Gwaii. They used lidar data to create a DEM of the island and search for raised, slightly sloping terraces inland from the current shoreline. These features are indicative of an ancient, or palaeo, shoreline. Although sea level has risen globally since the last glaciation, isostatic rebound resulted in a lower relative sea level on the island. The researchers were looking for areas that were close to a straight palaeo-shoreline and relatively flat. They classified these areas as having high archaeological potential because they are ideal for human habitation.

Identifying sites of high archaeological potential allows targeted digs to be performed. Without the help of lidar-derived images, archaeologist Nicole Smith compares searching for archaeological sites to “looking for a needle in a haystack”. On Quadra Island, 12 dig sites were chosen from the locations identified in the DEM as having high archaeological potential. Archaeological material, primarily ancient stone tools, was found at eight of the sites. The success of the digs provides substantial evidence that Quadra Island, and likely the surrounding archipelago, were inhabited for an extended period of time following the last ice age. It also adds to the growing body of evidence indicating there were people in North America a few thousand years earlier than previously believed.

As Canadians, understanding our history is crucial for understanding how people before us have used the land. Lidar, never intended as an archaeological tool, is being repurposed to help us do this. Who knows what we will discover next, or what tools we will use to make these discoveries?

~30~