Pascal Lapointe and Karine Morin, Science Policy co-editors

In early August, the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development (DFATD) announced that Canada would provide $3.6 million dollars to both the World Health Organization (WHO) and Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) to help the international Ebola effort. This was not the first Canadian contribution; as early as April 18th, three ministers (International Development and La Francophonie, DFATD, and Health) had pledged nearly $1.3 million to address the Ebola outbreak.

However, financial aid alone cannot put an end to the suffering. Indeed, on September 2nd, Médecins Sans Frontières denounced the lack of deployment of resources. “Six months into the worst Ebola epidemic in history, the world is losing the battle to contain it,” said its international president, Dr. Joanne Liu. A few days earlier, Canada had pulled its three-person mobile Ebola laboratory from Sierra Leone after several people in their hotel were diagnosed with Ebola, though it was re-deployed on September 6th.

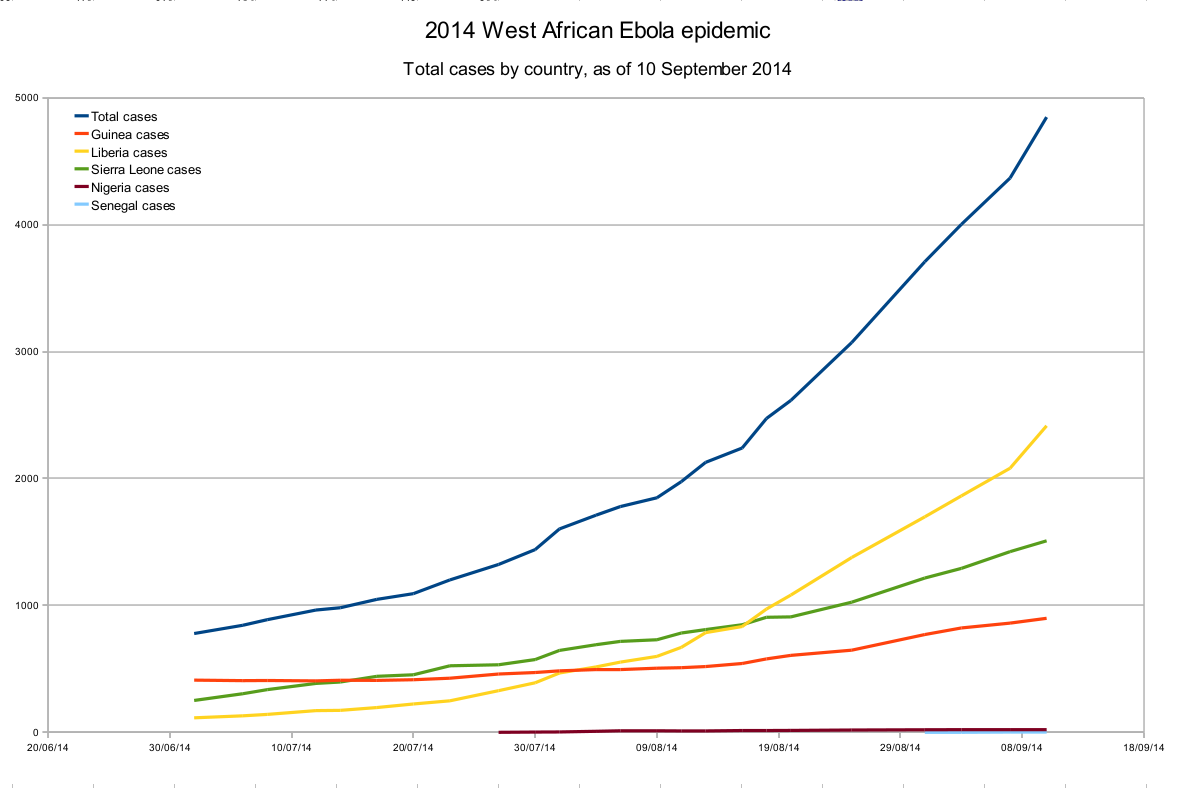

West Africa Ebola 2014 cumulative cases by country as of Sep 10 (by The Anome – Own work. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons).

While questions regarding lack of sufficient international help to fight the Ebola outbreak have been the subject of a news report in the New York Times and an editorial in Nature, there has been little discussion of it on our side of the border.

Canadian science bloggers like Agence-Science Presse have stepped in to fill the mainstream media gap:

“In 2003, an outbreak called SARS provoked an international reaction of a magnitude never before seen in the face of a new virus. In 2014, in contrast, the slow reaction to Ebola is denounced almost daily by the World Health Organization (WHO) and by doctors in the field. The difference? Ebola is in Africa.”

This paragraph opened an Agence Science-Presse blog about Ebola posted last Thursday, September 11th. The post was inspired by two critical opinion pieces, which a few years ago would have been published in the op-ed pages but today provide excellent examples of how powerful blog posts can be in the face of a combined science and policy crisis.

The first opinion piece appeared in the guest blog section of the Washington Post on August 25th, in which two social science researchers attributed this unequal response to SARS versus Ebola to a “long and ugly tradition of treating Africa as a dirty, diseased place.” Building on this was a September 9th post by infectious disease expert Judy Stone on the Scientific American blog network, which drew parallels between the Ebola outbreak and the scandal following Hurricane Katrina in 2005: the slow reaction of American authorities revealed a huge gap between the rich (saved) and the poor (left to their own devices). “In the same way,” wrote Stone, “Ebola… is largely killing the poor, who are people of color, to boot. They are almost voiceless. And their deaths don’t threaten the economies of wealthy countries,” as SARS did in 2003.

While the response to the Ebola crisis is mired in social and political controversy, Canada made a major scientific contribution to the fight against Ebola by donating to the WHO available doses of an experimental vaccine (VSV-EBOV) developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and scientists at the Agency’s National Microbiology Laboratory. Given the genesis of this vaccine, however, the Government of Canada owns the intellectual property associated with it (although the rights to further develop the product for use in humans have been licensed to a US company, BioProtection Systems).

As reported in Maclean’s, researchers at the same lab have also been involved in the development of a therapeutic Ebola intervention (Zmapp), including Dr. Gary Kobinger who has been featured and quoted in a number of news stories, some dating back to 2012 when his work on Ebola was already receiving attention.

While these are accomplishments that Canadians should be proud of, they pose an interesting science policy conundrum. Not only is Canada using the Ebola outbreak to promote research from which it will benefit financially, but the source of funding for this research was actually a program led by Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC), rather than a public health initiative. This program was introduced in response to the events of September 11, 2001, and was intended to help defeat chemical, biological, and radiological-nuclear threats.

Comparing the international and Canadian response to SARS and Ebola are rich cases for policy analysis when examining science and the politics behind it. They raise questions familiar to many, including investment in rare disease research; intellectual property rights, patents and licenses; health care resources in the developing world; international aid in the form of medication, and more. But, more fundamentally, these comparisons may lead us to ask: in whose interests do we fund science? And to what end?

One thought on “The Canadian response to Ebola: a new science diplomacy?”

Comments are closed.