Ainslie Butler and Lindsay Jolivet, Health, Medicine, and Veterinary Science co-editors

This summer, I made friends with a zombie mouse.

One recent evening as I was sitting in my suburban Toronto backyard, a tiny mouse that often visits began behaving strangely. Instead of scurrying across the patio like usual, my mouse buddy started running in circles, seemingly unafraid of me or the noises I made to scare him off. As he kept circling me and stumbling around, something I learned in my undergraduate parasitology course came back to me: toxoplasmosis. This mouse was most likely infected with Toxoplasma gondii and I was probably witnessing parasitic mind-control in action.

Toxoplasma gondii contaminates the environment through cat feces, which are consumed by mice and birds. Cats then eat the infected mice and birds. Photo © Alexas-Fotos, CC0, via Pixabay

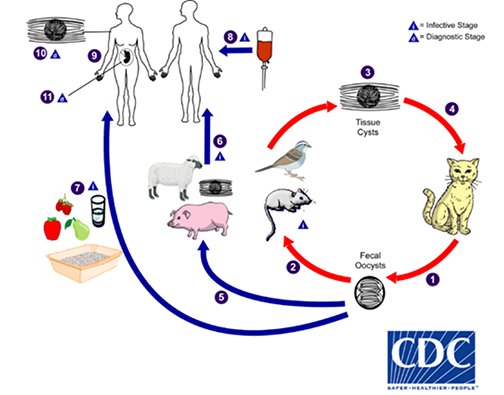

Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread parasite that relies on house cats and their relatives for survival. T. gondii typically contaminates the environment through cat feces, which are consumed by mice and birds. Cats eat the infected mice and birds, and the parasite is spread back into the environment through cat feces. T. gondii in the environment can and does lead to infection in almost any warm-blooded animal, and even marine species, but the pathogen can only complete its life cycle in cats.

What’s amazing about toxoplasmosis (the infection caused by T. gondii) is that it controls the minds of mice to make them easier prey for cats, increasing the odds of the parasite completing its life cycle. Infected mice lose their fear responses to odours associated with cats, and have even been shown to approach things that smell like cats, like cats, or (apparently) my ankles, which my kitty loves to rub against.

Mice infected with T. gondii often lose their fear responses to odours associated with cats, and have even been shown to approach cats. Photo © gere, CC0, via Pixabay

As if this wasn’t creepy enough, T. gondii can infect humans too, through consumption of undercooked or raw foods, contaminated drinking water, and through contact with cat feces (e.g., when I scoop my cat’s litter box – thanks Cleo). Fortunately for cat owners, the parasite needs time in the environment to ripen and become infectious – between one and five days, depending on conditions. This is a great motivation for me to scoop my cat’s litter box every day!

Nonetheless, research in Canada suggests that between 8 and 50 per cent of adults have been infected with Toxoplasma. These infections are generally harmless to humans, although some people may experience flu-like symptoms which often last about seven days. When T. gondii enters the human body, it typically forms benign cysts in muscle tissue and occasionally the brain. These cysts remain in the human body indefinitely, and under normal circumstances do not cause further infection or disease. Once a person has been infected with T. gondii, they develop immunity to that strain; however, because there are multiple strains of T. gondii, people can become infected more than once if they are exposed to different strains.

Despite being benign in most cases, toxoplasmosis can have serious side effects for some at-risk groups. For example, recent international research suggests that as many as 60 per cent of women of reproductive age have been infected with Toxoplasmosis at some point. This is a concern because T. gondii can cross the placenta in pregnant women and infect their growing babies. Congenital toxoplasmosis can disrupt neurological development and lead to blindness and other neurological issues in infancy or later in life, and can even cause miscarriages.

This is why many pregnant women are cautioned not to scoop Sir Fluffington’s litterbox. Generally, congenital toxoplasmosis occurs when women become infected during pregnancy, although there have been cases where women became infected before becoming pregnant or where immune-compromised women experienced a “flare up” from a previous infection.

But what about that loopy little mouse in my backyard? If toxoplasmosis can make a mouse walk right up to a cat, you might be wondering if it can change the behaviour of infected humans as well. Worryingly, some evidence indicates that T. gondii parasites can indeed affect human personality, behaviour and culture. Research has linked toxoplasmosis to traffic accidents, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and general psychoses, although much more research needs to be done before we can conclude that cats can drive you crazy.

The presence of T. gondii in Arctic fox populations may help it spread throughout Canada’s northern food chain. Photo © Pexels, CC0, via Pixabay

The story gets even more interesting when you look at the effect that climate change is having on the geographical range of toxoplasmosis in the environment. Canadian research suggests that up to 50 per cent of toxoplasmosis in Canada may be foodborne, via undercooked meats or contaminated water. Freezing and/or completely cooking meats are the best ways to reduce foodborne toxoplasmosis, and this susceptibility to freezing has acted as a barrier to the spread of T. gondii into Canada’s North.

However, with rising temperatures across the Arctic tundra, researchers are finding toxoplasmosis in new and startling places, including beluga whales and Arctic foxes. Recent research from the University of Saskatchewan suggests that the presence of T. gondii in Arctic fox populations may help it spread throughout Canada’s arctic food chain. It had been assumed that toxoplasmosis rates in remote, Northern Canadian communities would be low, but recent research has shown an exceptionally high proportion of Inuit women in Northern Canada with evidence of previous T. gondii infection.

Changes in the spread of toxoplasmosis highlight that new human populations could be at risk, especially already vulnerable Inuit populations. These populations typically consume significant amounts of undercooked meat – increasing the risk of toxoplasmosis as the Northern climate warms.

From behaviourial change to climate change, these issues highlight the need to take a closer look at the risks that toxoplasmosis might pose to food security and public health. Who knew a zombie mouse would have so much to tell us?

–30–

Another parasite that causes this behavior is raccoon roundworms. They don’t hurt raccoons but invade the brain or other nervous tissue and often do cause circling and stumbling until the animal finally dies.