Sarah Boon, Environment & Earth Sciences co-editor

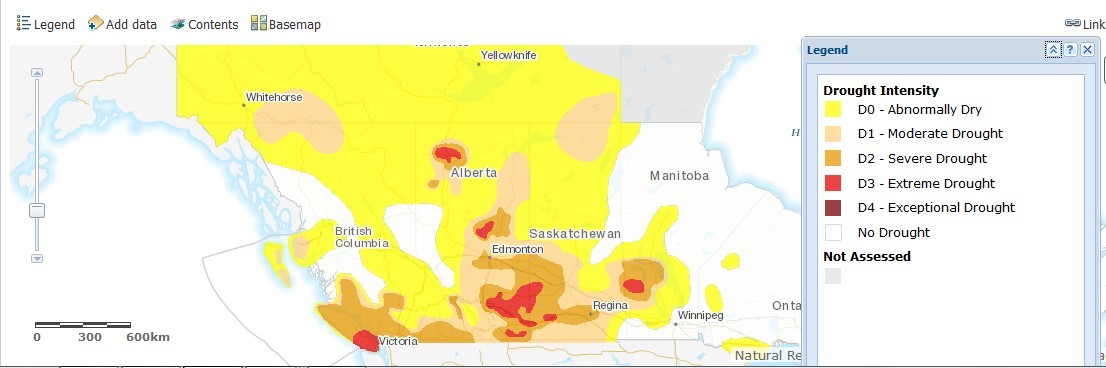

Western Canada has been experiencing unprecedented warm and dry conditions this year, leading to drought conditions across the region.

Map from Agriculture Canada’s Canadian Drought Monitor application.

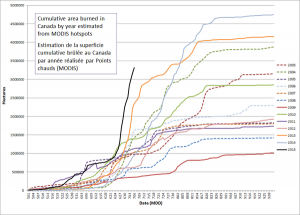

This has resulted in farming woes, increases in both the number of wildfires and the area burned by those fires (see plot below), water restrictions across western municipalities, and negative impacts on fisheries and hydropower generation.

Estimates from @NRCan scientists show more hectares burned in less time this year than any other on record #wildfires – Glenn Mason (@Glenn_A_Mason) July 7, 2015

So it was timely that WWF-Canada released their new Watershed Reports online tool last week. Focused initially on 12 watersheds around the country, with 13 more to be completed by 2017, the application allows users to learn about the state of their local watershed with just a few clicks.

The state of the watershed is defined using a number of indicators of both watershed health and threats. The health indicators (ranked from very good to very poor) include water quality and quantity, and fish and macro-invertebrate populations, while the threats (ranked from no threat to very high) include pollution, climate change, invasive species, overuse of water, habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, and alteration of water flows. The researchers also recorded whether or not there was enough data available to assess each indicator. For more details, see the health indicators technical protocol and the threats technical protocol.

Of the assessed watersheds, only the St. John and St. Lawrence watersheds achieved a score of good health, as most watersheds are significantly impacted by both pollution and habitat fragmentation. By far the biggest problem in accurately assessing watershed health, however, is the lack of key data for locations across the country.

Given our current drought situation – and the prediction of more frequent weather extremes in future, from droughts to floods – a little more data would go a long way. But the lack of water data is a common refrain across the country. We don’t have enough stream gauges to monitor river flows – or stations monitoring water quality – particularly in the North. We have a limited understanding of our groundwater amount and quality. Our data on aquatic ecology is unevenly distributed across the country and outdated around the Great Lakes…the list could go on.

Yes, Canada is a big country – but without this critical information we’re handicapped in our ability to make major water-related decisions; for example, British Columbia’s Site C Dam project and their sale of groundwater to Nestlé.

As Stu Hamilton writes on the Aquatic Informatics blog, increased water monitoring is a win-win for everyone, from policy makers to citizens, and governments to weather forecasters. It’s just who’s prepared to pay for it in advance, rather than having people pay later from the consequences.

2 thoughts on “Water problems in water-rich Canada”

Comments are closed.