Raymond Nakamura and Katrina Vera Wong, Multimedia co-editors

This fall, Curiosity Collider (CC), a Vancouver-based nonprofit that brings together art and science, launched their first Collisions Festival, a sci-art festival that ran from November 8 to 10 at Vancouver’s VIVO Media Arts Centre.

“There is no dedicated sci-art gallery space or any exhibition events in Vancouver that specifically showcase sci-art,” CC Creative Director and festival curator Char Hoyt says. “So we designed our Collisions Festival to fill that gap and give those artists an outlet for their work.”

In this inaugural festival, a line-up of individual artists and collaborations between artists and scientists explored the theme of “Invasive Systems” and the impacts of disrupting established patterns of living. Through works of art, an interactive workshop, curator tours, and guided discussions, “Invasive Systems” showcased a spectrum of invaders that ranged from plants and fungi to humans and technology. Here is our take on the pieces, presented as they were laid out in the gallery.

At Chris Dunnett’s “Viewpoints,” visitors sat and watched two screens, each showing a radio perched either on a beach in Newman Sound or in the woods of Southwest Brook. These scenes seemed idyllic, but putting on the accompanying headphones brought on a deluge of radio voices and signal noise that overwhelmed the sounds of nature.

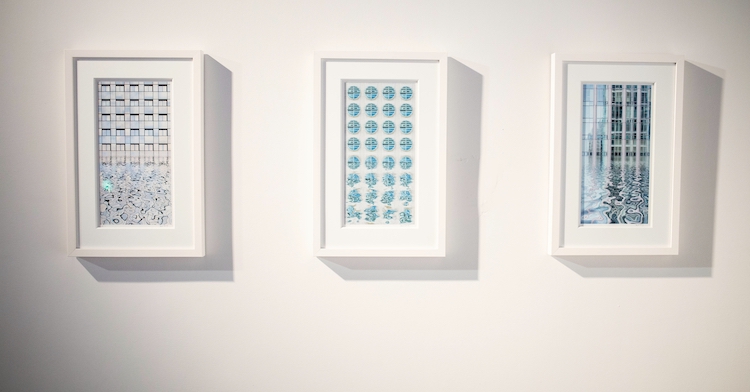

“Seawash, Research Centre, Double Reflector” by Christian Dahlberg; photo: Curiosity Collider / Sarah Race, used with permission

Three images of architectural forms by Christian Dahlberg hung along one wall. Among them was the BC Cancer Research Centre with its petri dish–like windows. In each, the repeating pattern established at the top of the image became digitally deconstructed toward the bottom, disrupting our sense of order.

A flimsy office chair invited visitors to take a seat at the workstation that formed Twyla Exner’s “Invasion”, where an unnerving infestation of multi-coloured wires, woven into organic forms, had overtaken a dated desktop computer and printer. Flowers and vines burst from the mouse and keyboard; mushroom-like blobs carpeted the inside of a CRT monitor; and tangled wires crept across the desk.

“Flora’s Song No. 1 in C Major” by Laara Cerman and Scott Pownall; photo: Curiosity Collider / Sarah Race, used with permission

The sweet tings of wooden mallets on a copper pipe glockenspiel played “Flora’s Song No. 1 in C Major” by artist Laara Cerman and molecular biologist Scott Pownall, who is a co-founder and the President of the Open Science Network. They transposed the music from a short DNA sequence of two invasive plants. Visitors turned a crank on the wooden music box that Cerman lovingly handcrafted. This set in motion an internal cylinder with pegs corresponding to notes, like in a player piano. Behind it hung Cerman’s signature works: botanical scans of the plants used in the song – creeping buttercup and brown knapweed.

Scott Pownall helps co-author Raymond look scientific; photo: Curiosity Collider / Theresa Liao, used with permission

Cerman and Pownall developed these ideas with 10 participants in their three-hour “DNA Sonification” workshop. Pownall demonstrated the process for sequencing DNA and Cerman had the participants perform as a human music box, playing an instrument as an assigned DNA base appeared on a screen. Like the music itself, the workshop was a bit random, but intriguing.

“Crossing” by Dzee Louise and Linda Horianopulos; photo: Curiosity Collider / Sarah Race, used with permission

In the centre of the space, visitors could try their gloved hands at arranging a large sliding block puzzle. Inspired by the research of Linda Horianopulos, a University of British Columbia PhD candidate studying the molecular biology of fungal pathogens and how they manage to invade the blood brain barrier, artist Dzee Louise painted “Crossing,” a white-and-grey-on-black acrylic image – resembling an x-ray – of a brain and gut mingled with branching nerves and spreading fungal colonies. Louise also snuck in two faces emerging from the web of nerves and cut the work into blocks for the puzzle, as a metaphor for exploring the mysteries of this system.

“Frankenflora, Lonely Hybrids: F. pruina, F. petra, F. harena” by Katrina Vera Wong; photo: Curiosity Collider / Sarah Race, used with permission

Nearby, visitors examined under a magnifying glass, the meticulous and ethereal Frankenflora created by our own Katrina Vera Wong. Designed to colonize different environments, these hybrid flowers physically recombined elements of native, cultivated, and invasive plants. Monographs described each flower’s imagined ecological adaptations and the traits of its constituent plants that would aid its invasive-ness.

Festival visitors watch a scene from “Polymer Legacy” by Kathryn Wadel and Garth Covernton; photo: Curiosity Collider / Sarah Race, used with permission

Kathryn Wadel created “Polymer Legacy” in response to Garth Covernton’s research on the prevalence and impact of microplastics in the marine environment. The installation used found plastic materials, some obtained from volunteering with the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup, which Wadel shaped into the geographic region around Vancouver. Projected upon it, a video depicted plastic waste infiltrating various habitats, while accompanying audio featured interviews with Covernton.

At the opening reception, mixed race Tahltan and inland Tlingit sound artist Edzi’u took the floor for a performance related to her installation “The Moose are Life,” where moose antlers hung before a projected map of the Tahltan First Nation territory in northern B.C., smeared with bloody red handprints. For her performance, Edzi’u moved the unbound moose antlers gracefully and purposefully to an audio recording of her father reflecting on the impact of the unregulated behaviour of non-resident hunters trespassing and hunting for mere sport, disrespectfully leaving moose carcasses, and decreasing moose populations.

Joanne Hastie discusses “Robot Paintings”; photo: Curiosity Collider / Theresa Liao, used with permission

Finally, anticipation rose as visitors watched the still arm of Joanne Hastie’s painting robot. It was choosing a colour. Hastie taught herself python code to train the robot to paint in her style, with finished paintings flush with abstract patterns and colours. Hastie uses an artificial intelligence classifier, familiar with her preferences, to sort through random ideas and learn what’s “good”/”bad.” She found that people, who observed the painting in progress, supposed that the robot arm should get most of the credit, but programmers appreciated that she rightfully takes credit for what is created.

Following an open discussion in the gallery on Saturday afternoon, visitor (and fellow SciBorg) Katie Compton said, “The ‘Robot Paintings’ installation really speaks to our society’s current fascination with and anxieties about the potential impacts of recent and new technologies, and how we can continue to live and express ourselves in a culture that has been invaded or disrupted.”

“We felt exploring this theme ‘Invasive Systems’ would encourage critical thinking, a better awareness of our world and what an invasive system could be,” event curator Hoyt says, “The theme also spreads itself across a number of different scientific disciplines, which was important for us in order to engage more artists and scientists for participation.”

A promising first, this Collisions Festival demonstrated that when art and science invade each other’s spaces, fascinating ideas can emerge. If you missed it this year, follow Curiosity Collider @CCollider for updates on next year’s festival and check out their year-round art-science events, like the Collider Cafes.

~30~

Its amazing to read the amalgamation of science and art at different levels. I am well acquainted with Science illustration, science infograph, scientific art; but these experiments of converging DNA and music seems out of my mental vision. I had never thought about it. I hope I could experience such scientific handles one day.