Michael Ralph Limmena, Health, Medicine and Veterinary Sciences editor

In the wake of the Canadian government’s approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines in December 2020, many Canadians are eager to get vaccinated. However, some people remain hesitant.

According to an IPSOS survey of 1,001 Canadians in November 2020, 28 per cent would wait six months to see whether the new COVID-19 vaccines are effective before getting vaccinated. Similarly, a January 2021 Angus Reid survey of 1,580 Canadians found that 56 per cent of respondents between the ages of 18 and 54, and 17 per cent of those over 55, would wait to get the new COVID-19 vaccines.

Reasons for vaccine hesitancy are complex and include fears about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines due to their rapid development, skewed risk perception, and mistrust of medical institutions.

Fears about safety

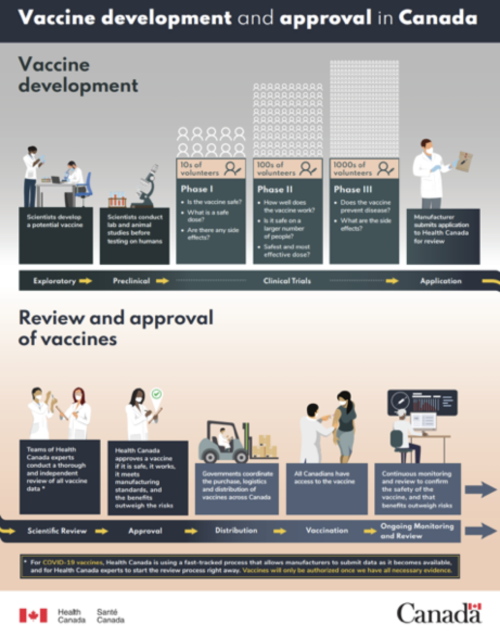

The development of the COVID-19 vaccines in about 11 months has led to some fears about whether they are safe. However, these vaccines have undergone the same rigorous clinical trials, overseen by Health Canada, as any other drug. These clinical trials occur in three phases and can take as long as 10 years.

Check out this poster by Health Canada about the vaccine development and approval process in Canada.

In the first phase, a small group of volunteers receives the vaccine to test its safety and determine optimal dosage. In the second phase, at least 100 individuals receive the vaccine to determine its effectiveness and the appropriate immunization schedule, identify side effects, and monitor its safety. In the third phase, at least 1,000 individuals receive the vaccine to compare its effectiveness with existing vaccines, monitor its safety, and identify any adverse reactions, which are more likely to be detected in a larger, more diverse sample of recipients. Health Canada reviews the results of each phase and determines whether the vaccine should advance to the next phase, and, eventually, the market.

Clinical trials are the part of vaccine development that takes the longest, usually lasting between six and nine years. All vaccines must undergo this strict process before Health Canada approves them. Even after approval, vaccinated individuals are monitored for additional side effects as long as the vaccine remains in use. Lack of funding and trial failures (most vaccines don’t pass clinical trials) can extend the time required to develop new vaccines, which explains why the entire process of developing a vaccine typically takes 10 to 15 years.

Researchers developed the COVID-19 vaccines faster than any other vaccine in history. Unlike previous vaccines, they were built on knowledge gleaned from studies of similar viruses. Moreover, significant public and private fundingsupported their development, and, to save time, regulators allowed all three clinical trial phases and regulatory evaluation to run concurrently. These time-saving measures enabled the development of effective and safe vaccines in less than a year.

Despite this, some Canadians are still concerned about possible adverse reactions to the vaccines. But adverse reactions to vaccines are rare, typically occurring within weeks of vaccination, and the most common adverse reactions are usually identified in the third phase of clinical trials. Although we may not yet be aware of all possible adverse reactions to the approved COVID-19 vaccines, vaccinated Canadians will be monitored to detect these effects. Given the possible repercussions of contracting COVID-19 (extreme illness or death), most experts agree that the benefits of being vaccinated outweigh the unlikely possibility of adverse reactions.

Skewed risk perception

In addition to misunderstandings about vaccine development, cognitive biases may also contribute to vaccine hesitancy. Cognitive biases are patterns of thinking that help us process information quickly but often lead to errors in judgment. When some Canadians think about the COVID-19 vaccines, they may recall the cases of vaccinated people developing Bell’s Palsy or Guillain-Barre Syndrome, even though research shows no association between the vaccines and either condition. Focusing on these notable but rare cases is an example of the availability heuristic, which is a mental shortcut. People evaluate the risk of an event occurring based on the examples that come immediately to mind. In this case, more memorable but improbable events (e.g., developing Bell’s Palsy) are perceived as more probable than less memorable events (e.g., muscle soreness) even though the actual odds suggest otherwise.

Researchers have also found that anticipated regret associated with getting vaccinated plays a role in predicting behaviour. Studies show that people experience more regret when their actions lead to a negative outcome (e.g., choosing to vaccinate and experiencing side effects) because actively intervening and experiencing a negative outcome leaves individuals vulnerable to self-blame. They experience less regret when their inaction leads to a negative outcome (e.g., choosing not to vaccinate and contracting the disease) because people are less likely to blame themselves when their actions did not cause the negative outcome.

Mistrust of medical institutions

Lastly, mistrust of medical institutions is likely contributing to vaccine hesitancy, especially among Indigenous communities. Canada’s history is fraught with tragic experiments involving Indigenous peoples. These include depriving children of food and nutrients to determine whether nutritional supplements can treat malnutrition, and testing the safety of a tuberculosis vaccine in infants. Although there are almost no statistics on vaccine hesitancy in Indigenous communities, it is unsurprising, given this history, that many Indigenous individuals mistrust the medical system. Delving into the complex issue of Indigenous mistrust of medical institutions is beyond the scope of this article, but further information can be found at the First Nations Information Governance Centre, Reconciliation Centre, and many others.

As of February 11, provincial and territorial governments across Canada have administered approximately 1.15 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, prioritizing healthcare workers, the elderly, and Indigenous adults residing in Indigenous communities. However, production delays of the vaccines have slowed the rollout. Nevertheless, between the two vaccines, the government expects six million doses to be delivered by June.

Vaccination against COVID-19 is essential to protect ourselves and others, especially children and seniors, from the disease. If vaccination rates remain low, we extend the pandemic lockdown and make it more difficult to visit friends, family, and loved ones. With high vaccination rates, we can protect everyone and make COVID-19 a distant memory.

~30~

Banner image by Whitesession, CC0