Jamie D’Souza, guest contributor

Since the 1960s, Churchill, Manitoba, the self-proclaimed ‘polar bear capital of the world’, has attracted thousands of tourists who hope to see polar bears lounging in the willows or on the shoreline of the Hudson Bay. But spotting a polar bear in its natural habitat near Churchill may soon become less frequent. Climate change negatively impacts the northern regions. Tourists are becoming increasingly aware that they need to venture north sooner rather than later to see these magnificent animals in the wild, creating a ‘rush’ to the Arctic.

A map showing the VIA Rail line from Winnipeg to Churchill, Manitoba. Source: Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

There is an underlying relationship between tourism and climate change. Tourism industries like the one in Churchill experience the effects of climate change and contribute to them. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has quantified how our dependence on fossil fuel energy, unethical deforestation practices, and excessive carbon-emitting infrastructure projects contribute to the warming of our planet.

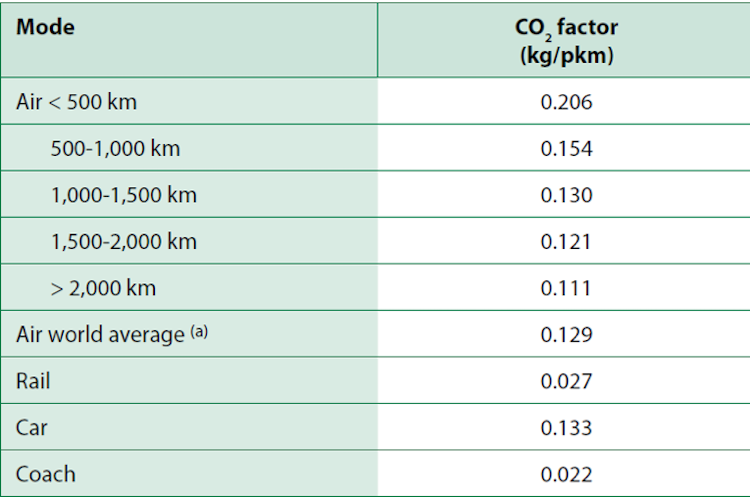

My 2018 study, supported by Dr. Jackie Dawson and Dr. Mark Groulx, measured the emissions from Churchill’s polar bear viewing industry. The calculation included emissions from transportation (air travel to and from Churchill), accommodations, and activities (polar bear viewing tours, scenic helicopter flights, tours of the town and travelling to a dog sledding location). For the 2018 polar bear viewing season, we estimated that the industry produced 23,017 tonnes of CO2. Air transportation accounts for most of these CO2 emissions from tourism (see table below). Churchill is not linked to the rest of the province by road. Cruise ship travel is seasonal and also carbon-intensive. The only viable travel options available to tourists are flying into Churchill from Winnipeg (the hub city) or taking a 46-hour train ride (when operational). Most tourists fly.

An example of emissions factors for tourism transport modes in Europe .A pkm is a passenger-kilometre. This unit of measurement represents the transport of one passenger by a defined mode of transport over one kilometre. Source: World Tourism Organization and United Nations Environment Programme, 2008, page 135

Climate change negatively impacts sea ice and snow. In turn, these environmental changes affect migrating birds and other Arctic wildlife, including the polar bear. Polar bears depend on the sea ice for hunting, using it as a platform to catch their main source of food: ringed seals. The Western Hudson Bay (WHB) polar bears congregate along the western shore of the Hudson Bay in October and November, and wait for the sea ice to form. Once the sea ice cover becomes established, the bears begin their eight-month feeding and breeding periods. Warmer air temperatures mean the ice freezes up later and breaks up earlier. This abbreviated sea ice season shortens the polar bears’ hunting season, which has led to a decline in the health and population size of the WHB polar bears.

The polar bear has become a symbol of global climate change and the last chance tourism trend. This trend means tourists are drawn to locations whose landscapes, natural systems or cultures are vulnerable to changes either due to global warming or other anthropogenic factors such as globalization and modernization. The media has portrayed Churchill as a place to visit ‘before it’s gone’ and has influenced the tourism demand there.

Tourists embarking on a last chance tourism experience don’t intentionally contribute to the effects of climate change. Last chance tourism studies show that these people have a strong understanding of their effects on the environment and they participate in sustainable practices at home. However, the sense of urgency and desire to see the polar bears before they disappear tend to outweigh their environmental values.

Many tourists are unaware of how much air travel contributes to climate change. After all, the effects of air travel are cumulative and take time to trigger climatic changes. A tourist may not be able to recognize the impacts on his single trip even though the CO2 emissions from one trip greatly exceed the per capita emissions of the average world citizen. If climate conditions at Churchill change so much that tourists cannot see polar bears there, they will travel to places further north, creating even more CO2 emissions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has temporarily halted the tourism industry, but it is likely to explode in the future. We need to act now if we want to make tourism more environmentally friendly. For example, we should promote more sustainable modes of travel, such as trains. A train trip is not only less carbon-intensive but allows for a very different tourist experience than flying.

There are many opportunities for tour operators to begin talking about the relationship between climate change and tourism. Educating tourists about the impacts of tourism before, during and after their trips and providing them with alternatives, ideas, and solutions about what they can do to reduce their effects on the climate and environment is an effective mitigation strategy. It is a strategy that allows tourists to reflect on their travel decisions and begin to consider solutions and alternatives that exist and demand changes that reduce emissions.

Education does not have the same impact on reducing CO2 as switching to low-carbon forms of transportation. However, making more informed decisions about our travel options is one way we can protect Churchill’s (and the world’s) wildlife and the tourism industry that depends on it.

~

Follow Jamie on Twitter