Katrina Vera Wong, Multimedia co-editor

When I was 14, I was asked to mix some chemicals together for an exam. The result was a beaker full of dazzling, golden glitter. Until then, chemistry had been an interesting but purely academic subject. But once I saw that first sparkle, I appreciated it on a deeper level. It was a revelatory moment for an adolescent contemplating her future.

I ended up majoring in biology instead of chemistry. And I became a writer instead of a scientist. These decisions are matters of personal choice (and passion). But are there factors that could have directed me, and like-minded students, toward a career in science?

Science explains what the world is and how it works. To appreciate what it teaches us takes more than a hasty field trip once every few months, it takes time and active participation. A hands-on approach to teaching is one way to widen the scope of learning, but the term itself doesn’t quite do justice to what’s required.

Creator of Playful Content, Devon Hamilton describes hands-on learning as a subset of “experiential and participatory” learning, which engages all our senses. These sensory and immersive experiences “build powerful memories and observations, that scaffold the learning,” he explains. His work involves the development of informal learning environments as places to “experiment with education and learning models.” These could include an exhibition at a museum, a program at a park or other makerspaces. Textbook-knowledge is limited and organizations like Playful Content and Sea Smart are recognizing the need for fun, supplementary learning that takes place outside the classroom or curriculum.

So what does that mean for learning science? What does it mean to be prepared for a future in science? “We have an opportunity to spark interest and passion for science and learning at a young age by focusing on skills and process – developing [students’] critical thinking, inquiry-focused skills that future learning needs,” Hamilton says. “We know what the 21st-century skills are, and a more concentrated focus on those will help students become the lifelong learners we know they need to be.” To that end, a lot of emphasis has been given to coding skills and schools have begun prioritizing coding in their curriculum. Yet there are some who disagree with teaching methods that simply accumulate more hours in front of a screen.

One of them is Derek Wulff, a Victoria-based teacher and the founder and designer of Pathfinders (wooden science kits), who argues that a virtual learning experience has less engagement quality because of its convenience. “As soon as you have to explain things, you have to remember them … [With a] virtual experience, you don’t have to remember it because you can just look it up again,” he says. Instead, Wulff supports the power of language and the age-old skill of building.

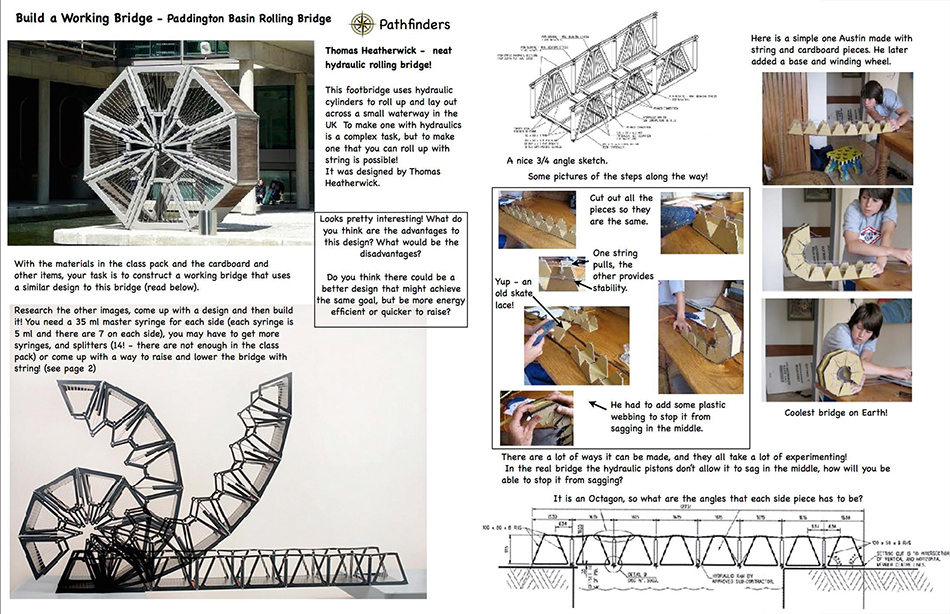

The development of language remains crucial, even if it pushes science down the list of priorities, as the ability to explain something clearly shows how well a subject is understood or remembered. Unlike IKEA, whose diagrams can set the calmest man ablaze, Pathfinders’ kits are accompanied by comprehensively written and illustrated instructions. Wulff asserts that “it’s incumbent upon us to continue to use words and not just turn everything into a drawing.”

Building a working bridge – Paddington Basin Rolling Bridge: A project you can do at home, courtesy of Derek Wulff.

Wulff is also proud that Pathfinders’ various machines are accessible to people of all ages. I used to work at a toy store that sold his kits and can testify to that claim. Customers would come in and buy them for their kids, friends, parents or grandparents. What makes the kits so appealing are the pre-cut materials and approachable building methods, which are key to making them usable. Says Wulff, “it’s the process, not the product.” Though customers see the finished product on the box, what they’re really buying is the ability to build it.

In a field like science where replicability is valued, it is also essential to learn to be consistent. And going through the physical motions of certain skills, whether it’s using your hands to build a machine or using your voice to explain a concept, is just as important as memorizing the facts.

And this approach isn’t just for students. “Some of the most important programs and activities that different science centres and museums [offer] focus on teacher development and training,” says Hamilton. There’s a range of programs, such as The Tech Challenge, designed to leave an impression on both students and teachers. Teaching teachers, and updating them on current research, are important parts of science education but there are other interactions worth bolstering. For example, parental involvement in a child’s education keeps both engaged in the subject, though the method of communicating that subject might differ.

According to Hamilton, when developing an exhibit for young children “the focus of the activities is on their developmental and learning needs – however, [we] target their parents with the communications about what is happening and why it matters.” At home, it might be challenging to play the role of a science teacher but if it’s where children are comfortable, given some one-on-one time, it could even be where they’re comfortable learning about science.

My father used to teach teachers and advised me to work hard and have fun. Learning science is not exempt from this notion of balance. Hamilton understands that “not everyone wants a physical experience, or a hands-on one, or a sophisticated computer visualization – but balancing all of these approaches maximizes your reach with different audiences.”

By focusing attention on the development of skills and approaching it from different angles, students can develop a better understanding of science and learn to appreciate the many ways in which it’s explored.

~30~

Featured image: Derek Wulff at Conference in Chongqing just after Christmas with students at an Educational Base school. Image courtesy of Derek Wulff.