By Patrick Jardine, new science communicator

Northern field work

The wolf carcass Blaine and Jamie brought back to show Jen and me after we had completed our field work for the day.

2:00 p.m. on March 9th, 2021: I was finishing sampling snow density along a mine access roadside in the central Yukon with my co-worker, Jen, when I heard branches breaking deep within the forest beside me. It was a balmy –15 °C out — a significant improvement from –54 °C the month before — and work was going smoothly.

But the noises were putting me on edge. They were getting closer, and similar sounds during last month’s trip had been followed by wolf calls from just beyond the treeline. As I was beginning to estimate how long it would take to run to my car if a pack of wolves came charging through the trees, I heard the hum of a snowmobile.

Moments later, my friends Blaine and Jamie from the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun First Nation raced out of the forest, hauling a dead wolf with them. They had found the carcass lying next to some moose remains frozen in a nearby river. This winter was my first time up north, and they knew I would love the chance to see a wild animal like that up close.

After checking it out and poking at its claws, I posed for a picture to send back home to Ottawa.

The problem

But I hadn’t come all this way to be distracted by wolf carcasses. I had work to do.

As members of the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun, the “Big River People” of Central Yukon, Blaine and Jamie’s home village of Mayo is one of many remote northern communities threatened by warming permafrost.

Permafrost is ground that has remained at or below 0°C for two or more years. As it warms up, it begins to lose its structural integrity, and if the ground contains ice, then thawing can cause it to subside — or sink — unpredictably.

Permafrost subsidence is a big problem for northern roads. It can reduce their stability, cause cracks to appear, and if left unchecked may even render the roads inoperable.

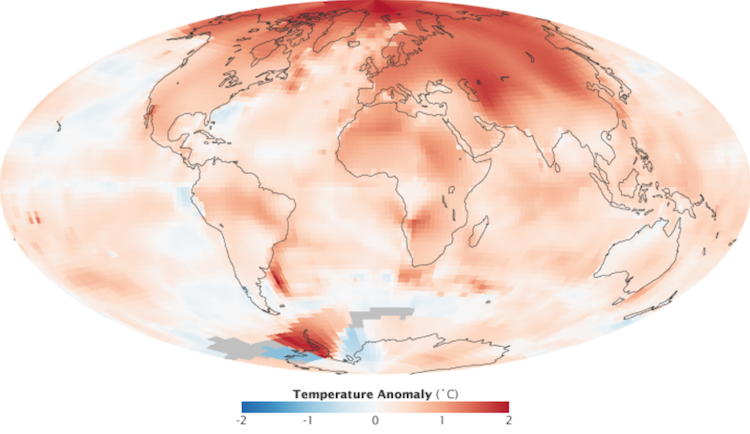

Accounting for this risk is made all the more difficult due to Yukon and the rest of the Western Canadian Arctic experiencing some of the most dramatic and rapid warming on Earth in recent years, as climate change tends to disproportionately impact polar regions.

An image of global temperature trends from 2000 to 2009 showing rapid warming in the Arctic, provided by NASA and uploaded to Wikipedia by Robert Simmon.

As a result, conditions in the north are quickly changing to a state beyond what the region’s roads were designed to handle, and maintenance costs are rising steadily. The roads must remain open to keep remote communities connected and ensure essential goods can still get in.

Some sort of remediation is needed.

That’s where my research comes in.

Crushing snow: A possible solution

I’m a Master’s student in physical geography at Carleton University. I’m studying whether compacting snow could serve as a new maintenance technique for keeping the ground cold and protecting permafrost.

Northern roads typically are designed on large gravel embankments which elevate them off the ground. This provides a buffer under the road surface, where thawing can take place without reaching the sensitive soil below.

This is generally effective, but the embankments can be several metres high, causing snow to pile up alongside them as it either gets blown there by the wind or cleared off the road surface by maintenance crews.

Previous research has shown that the greatest warming takes place underneath these snow piles.

Snow is an excellent insulator. Like a thick down jacket, it traps air in the pockets between the accumulated snowflakes, protecting the ground from cold air temperatures. When snow becomes compacted — by piling it up beside a road, for example — the air is squeezed out and the properties of the snow change to allow heat through more easily, like a thin windbreaker.

That’s the theory, anyway.

The research

Map of my field sites, where regular compaction and field measurements took place from November 2020 to June 2021.

To test that theory, Jen and I set up eighteen 50 × 5 m plots at several forested locations around Mayo and in a mountain valley 160 km to the northwest along the Dempster Highway, which links the Western Arctic to the rest of Canada’s highway network.

Temperatures under the snowpack were monitored by loggers at all plots. Half were compacted by Na-Cho Nyak Dun workers using snowmobiles each month, while the remainder were left undisturbed to establish baseline conditions. For several days after each compaction, Jen and I would measure properties of the snow, including density, hardness and grain shape, to see how they compared.

I’ve since returned to Ottawa and put together the results. Data from two of the dataloggers stationed near Mayo were unrecoverable, but for the remaining sites, temperatures were, as we had expected they would be, lower at each of the compacted plots, with an average temperature difference of up to 3°C over the winter.

The compacted plots also warmed up much faster during the spring. This suggests the lower average logger temperatures were actually due to a reduction in insulation, rather than just random variance. It appears much of the change in thermal properties may result from crushing depth hoar, the low-density, crystalline snow that typically forms at the bottom of the snowpack.

More experiments are needed to determine the technique’s effectiveness under different conditions and to better understand the physics behind it, but it shows promise as a tool for northern maintenance crews to treat high-risk sections of road and adapt to a rapidly warming climate.

Feature image: Tombstone Mountain near the Dempster Highway field site.

Patrick Jardine is completing his M.Sc. at Carleton University. He wrote this article as part of Science Borealis’s Winter 2022 Pitch & Polish, a mentorship program that pairs students and researchers with one of our experienced editors to produce a polished piece of science writing.

Read more about Pitch and Polish

This post is interesting and helpful for me. Thanks.