By Naeema Bhyat, guest contributor

With Canada’s wide expanses of forest, grasslands and shrublands, wildfires have always been part of our landscape. But as more Canadians experience eerie, smoky skies and a dull orange sun, these fires loom larger in the public’s imagination. Events like the 2016 wildfire that tore through Fort McMurray, Alberta and the 2021 fire that destroyed Lytton, British Columbia filled our news screens for weeks. The Fort McMurray wildfire is among the country’s costliest natural disasters, while the Lytton fire was preceded by Canada’s highest-ever recorded temperature of 49.6C. With climate change and hotter and drier weather, fire season is predicted to get longer and more intense and that has big consequences for people and wildlands.

So far in 2022, most parts of the country have seen fewer fires than usual thanks to a cool, late, and wet spring. However, fires like the ones in 2016 and 2021 illustrate what can happen: forced evacuations, threatened communities and large areas under heavy smoke watches and air quality alerts. Even large urban centres away from forests are susceptible to smoke drifting in over long distances from fires burning hundreds of kilometres away.

The importance of wildfires

Wildfires arise through both natural and human-driven processes including lightning strikes (about half) and sparks from vehicles or industrial processes. They can ignite from deliberate arson or accidentally dropped cigarette butts or campfires that spread to nearby brush, leaf litter or trees. Prescribed burns are fires deliberately set by forest or land management agencies to renew old forests, reduce the impacts of uncontrolled fires, create wildlife habitats or reduce fire risk to human areas. In the natural context, fires are part of the forest life cycle and the seeds of some tree species require fire’s high heat to germinate, while other species thrive in fire’s aftermath.

As beneficial as wildfires can be, longer and more intense fire seasons are a serious concern. Uncontrolled fires and smoke threaten human health, as well as individual lives, property, communities, homes and infrastructure. They present a risk to livelihoods in industries like tourism, energy, agriculture, viticulture, transport and forestry. Fire’s costs range from insurance and economic losses to environmental, health and the deeply personal.

Predicting and managing fire risk

To address fire risk, Canada has a well-established and sophisticated fire prediction system that has been adapted by several countries for the development of their own systems. Prediction systems and risk-management tools like FireSmart are used to understand and manage fire threats. In residential areas, local vegetation might be trimmed or removed to reduce fuel buildup. Homes and communities can be planned on terrain and constructed from materials that are less susceptible to rapid fire spread, although it may be impossible to avoid drifting smoke. Managing risks at industrial sites can include effective emergency preparedness systems, reducing the potential for vehicle heat or sparks to set off fires, and managing local vegetation to reduce fuel buildup.

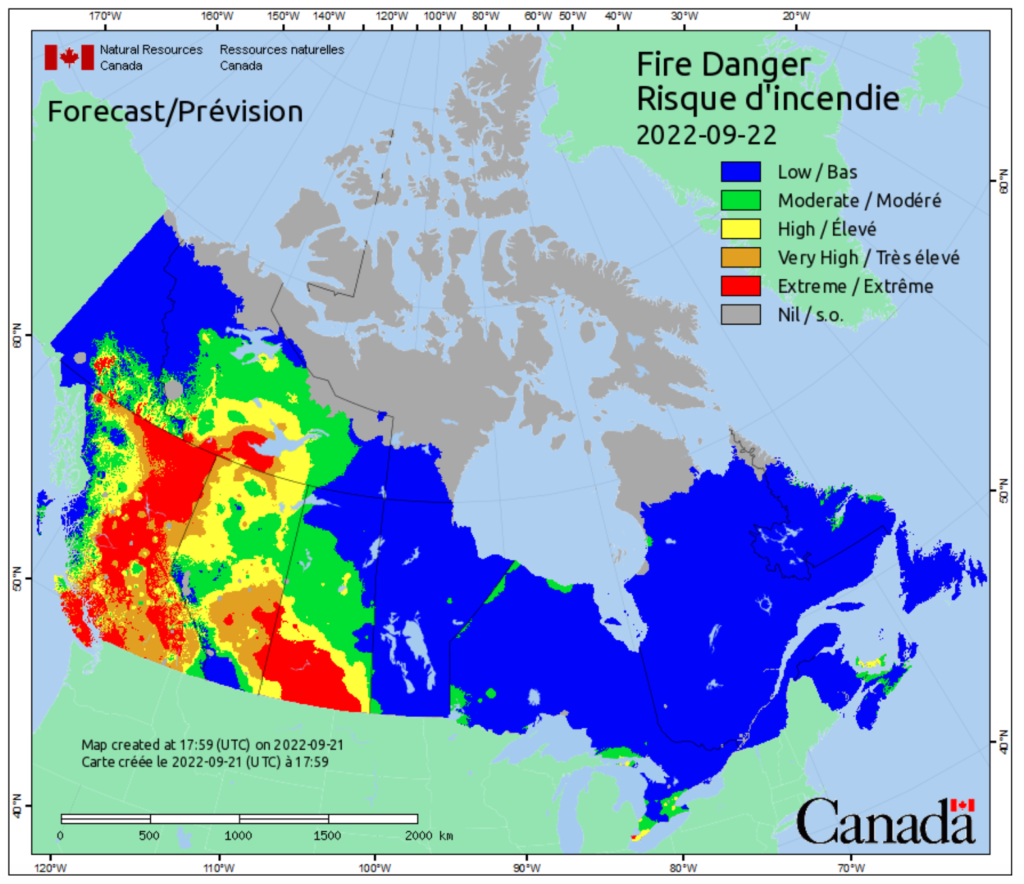

Canada’s Fire Danger Index. Source: NRCan.

On a national and provincial level, Canada employs various fire prediction systems. Natural Resource Canada’s Canadian Wildland Fire Information System (CWFIS) integrates data from long-range weather models with estimates of fuel loads and moisture conditions across the country to generate regional estimates of fire danger. CWFIS takes into account the amount of vegetation litter and organic layers, duff moisture, temperatures, and wind conditions. These factors give an indication of the danger of a fire igniting during hot, dry weather, how a blaze might spread, and its predicted speed and intensity. Provincial systems likewise integrate weather predictions, moisture, and fuel conditions to estimate risk and provide data to monitor active fires at regional levels.

Various governmental agencies use risk estimates and active fire monitoring to provide warnings to communities and recommendations for action including emergency evacuation. Industries use risk estimates to reduce or shut down their activities where fire poses a risk to operations or when their activities risk starting a fire.

Conventional fire prediction systems are, however, limited by the accuracy of the information on conditions and the complexity of predicting the weather and the behaviour of active fires. Currently, weather models offer reliable general long-range predictions such as forecasting a long, dry summer or a late, wet spring. Making more precise predictions far in advance is tricky due to the high variability in many factors that influence local weather: temperatures, wind, local terrain, or rain showers, for example. These variables make both forecasting and managing active fires more challenging.

Traditional knowledge

Fire in the forest Photo: Landon Parenteau, Unsplash.

In British Columbia and other regions, fire and forest management could additionally draw on traditional Indigenous knowledge developed and used over centuries, as recommended in a 2022 study by UBC researchers Hoffman and Christianson. Fire stewardship is especially important in forested regions where many Indigenous communities are located. Hoffman and Christianson’s recommended stewardship practices include controlled cultural burning, supporting resources that disseminate knowledge and training, smoothing jurisdictional barriers to fire and forest management, and building networks of fire keepers.

A more intense fire future

As the fire season lengthens and intensifies, the changing behaviour of forest fires themselves may become more significant in fire prediction. Journalist Ed Struzik writes that a pyrocumulonimbus cloud formed from the 2016 Fort McMurray fires generated a storm cloud and ground lightning strikes that touched off new forest fires distant from the initiating blaze. This made it harder both to predict how the fire would spread and to control the multiple fire sources.

Canadian agencies’ ability to manage wildlands, maintain effective fire prediction and warning systems, and develop resilient infrastructure and strong policies around fire and forest management will be urgently needed in the coming years. Effective planning and coordination between responsible agencies are critical. Canada’s success in these areas remains to be seen in a longer and more intense fire future.

Feature image: John Towner, Unsplash.

One thought on “How we predict and manage fire – and why it matters”

Comments are closed.