Susan Vickers, Communication, Education & Outreach co-editor

As a chemist passionate about outreach, I’ve spent a lot of time and effort trying to combat the public’s fear of chemicals, dubbed by chemists as “chemophobia.” It infuriates me when companies tout products as “chemical-free” (who wants to buy a vacuum?!), and am convinced that this has led to a general mistrust in chemists and chemistry. As a chemistry graduate student I spent far too many hours toiling away in a lab to allow these companies to ruin the image of my precious subject. And so in my spare time I’ve committed myself to the cause: to help rid the public of their fear of chemicals.

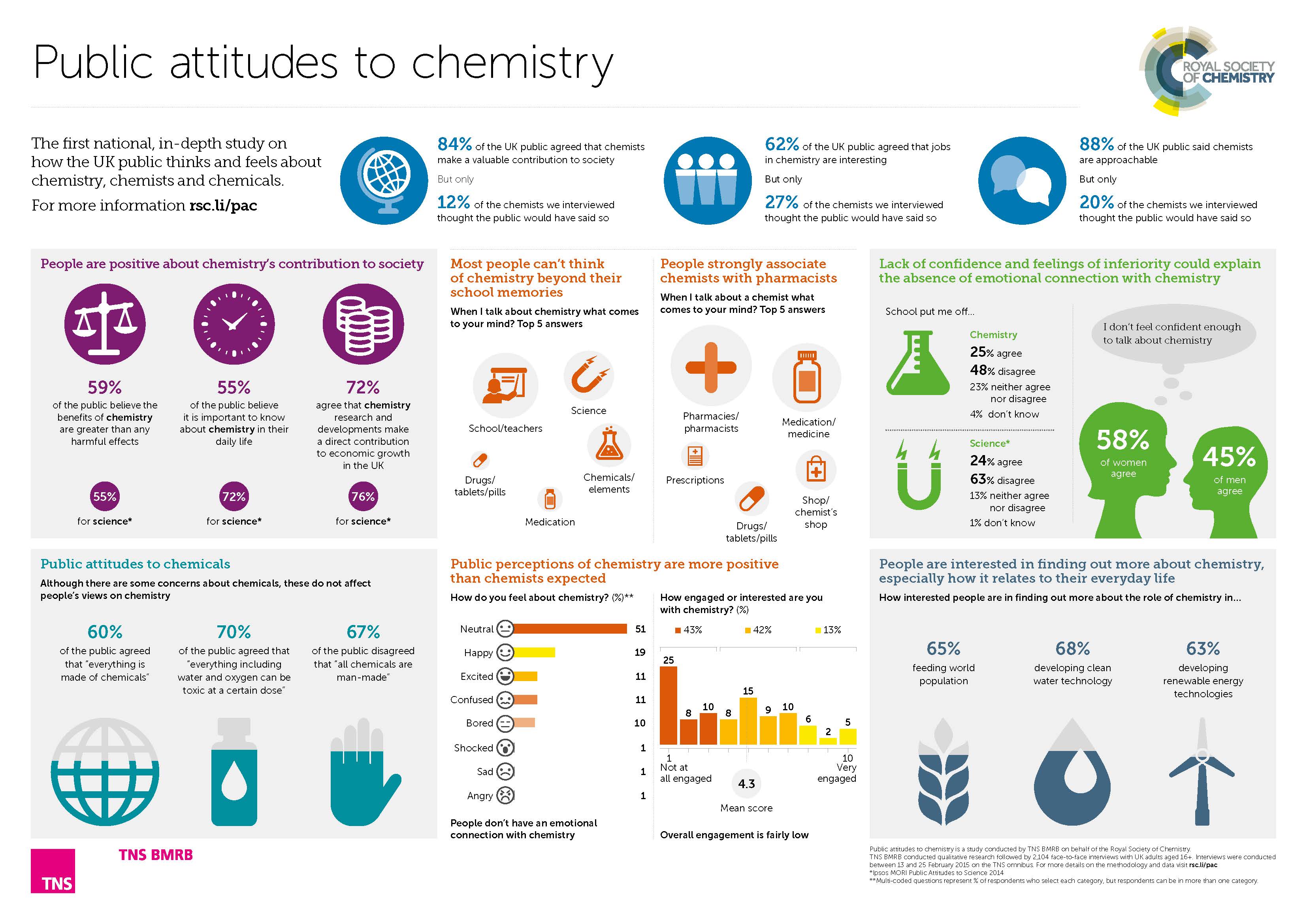

I’ve written blog articles and held events for both adults and children attempting to alleviate chemophobia, and was feeling pretty good about my mission until I read a recent report from the Royal Society of Chemistry. It suggests that the British public actually has a fairly high opinion of chemists and chemistry, and that chemophobia has been exaggerated by scientists.

Infographic from the Royal Society of Chemistry, used with permission. Click to see a larger version.

You don’t have to look very far to find a scientist protesting against the stereotype of the crazy-haired, white, male scientist – and for good reason. Yet are we scientists guilty of similarly stereotyping the public? Perhaps the field of science communication should stop and ask itself: who are “the public?”

The public is you, me, your neighbours, and your friends. Public opinion is the sum of a group of people, and can’t be determined using the opinions of one person, one institute, or one demographic alone. It’s not possible to design science communication programs ideally suited to the public from within the walls of an institution, cut off from the very people we want to engage. And to complicate matters even further, can a program designed for the public meet the needs of individuals?

Knowing your audience is key to the success of any interaction, from playgrounds to governments and everything in between. Many successful science communicators go to great pains to know and understand their audience. However, many passionate scientists do a substantial amount of outreach as a second, unpaid job. It isn’t feasible to ask these people to research their audience in great depth; there just isn’t the time.

Perhaps it’s time for science communication as a field to pause briefly and consider who the public is. Ask the audience questions and share your findings with other communicators so we can combine our findings and really get to know our audience. Help practicing scientists understand their audience and tailor their message accordingly – based on who’s actually listening to them, versus who they think is listening.

Who knows – maybe once we give up our stereotype of the chemophobic, uninformed individual on the street, the public will be encouraged to step away from that stereotype of the wild-haired, white, male scientist…