Katie Compton, Science Policy and Politics editor

Picture an engineer. Now picture a scientist. What images did you see? What do these people you envisioned look like?

Maybe you imagined a person working in a lab, or someone out in the field. Perhaps you saw a person at a podium giving a talk at a conference or in a classroom. Whatever you saw when you thought “engineer” or “scientist”, there’s a good chance that the person you conjured up in your mind was a man.

This is an example of implicit (or unconscious) bias. Our brains are wired to use mental shortcuts to help us understand and navigate our world. These shortcuts can come from many different sources – our parents and teachers, our own experiences, and the institutions where we learn and work. And these stereotypes have an impact on how we perceive and behave towards people.

Dr. Toni Schmader is the Canada Research Chair in Social Psychology at the University of British Columbia and the Director of the Engendering Success in STEM (ESS) Consortium. She is interested in how implicit gender biases create barriers for women studying and working in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). She is also an author on a recent study that showed that if a scientific evaluation committee has strong implicit gender biases and doesn’t believe implicit gender bias is a problem, it is less likely to select women for elite research positions. However, when committees acknowledged that gender bias is a problem in STEM, they did not show a preference for male candidates – even if the committees had previously scored high for implicit gender biases. This finding suggests that we can overcome our unconscious assumptions about other people.

Tools have emerged to help people learn about, and counteract their implicit biases. For example, the Canadian Research Chairs program has an online training module on unconscious bias to help peer reviewers learn about implicit biases and how these biases impact the reviewers’ assessment of research funding applications.

So, is simply educating people about bias the answer to reducing gender inequality in STEM? According to Dr. Schmader, raising awareness about implicit bias is a crucial first step, but we also need to find ways to motivate people to override their biases.

“The first thing to realize is that implicit associations (for example, the tendency to ‘think science, think male’) do not inevitably lead to biased decisions and behaviour,” says Dr. Schmader. “People can disrupt this link if they are aware of the potential for bias, care to make an effort to be unbiased, and prepare by actively preventing biased associations from shaping their behaviour.”

The ESS, a team of 70 researchers and partners who are looking for ways to break down barriers that hold back women and girls from exceling in STEM fields, is studying how stereotypes and implicit biases can create obstacles at different stages of life, from a girl’s earliest education experiences to a woman’s early career in STEM, and what interventions could help address these problems.

One of the ESS’s efforts is the RISE (Realizing Identity-Safe Environments) Project, which is trying to address the problem of women leaving engineering jobs at higher rates than men. Many women who walk away from the profession say they left, in part, because they didn’t feel welcome in the workplace. The ESS researchers have partnered with organizations that hire engineers, such as TECK Resources, the National Research Council of Canada, and Engineers Canada, to try to build cultures of inclusion where people can thrive, regardless of their identity.

The RISE project aims to build STEM workplaces where women feel welcome and recognized for their contributions. Image by Borko Manigoda from Pixabay (free for commercial use)

The RISE project has gone into these workplaces and hosted workshops designed to address two different issues that can lead to gender disparities in STEM: lack of inclusivity and preconceived notions about who can be a leader. Participating employees were randomized into either the inclusion or the leadership workshop.

“Our inclusion workshop is designed to cultivate more inclusive workplace cultures where everyone’s contributions are respected,” Dr. Schmader says. “The leadership workshop is designed to build everyone’s capacity to become more influential in their teams.”

The ESS team believes both workshops can help build workplaces where women feel they have a path to leadership positions and are respected for the work they do. The researchers plan to follow the participants over time to see whether the workshops have an effect on social dynamics in the partner organizations.

“We are measuring the degree to which people become more influential leaders and act as allies to those who might be marginalized,” says Dr. Schmader. “We’ll also be looking at how these changes in behaviour might lead to changes in women’s interactions and influence their team networks.”

Ultimately, Dr. Schmader and the ESS team want to identify how to translate what we know about implicit gender bias into changes in individuals’ behaviours and workplace cultures.

“I think it’s not enough to sit people in front of a webinar or video designed to educate people about bias and assume they will change their behaviour. People’s biases are supported by, and can be changed by, the surrounding culture of their organization,” says Dr. Schmader. “Interventions need to target not only individual beliefs but also the interactions between people and institutional policies and practices.”

~30~

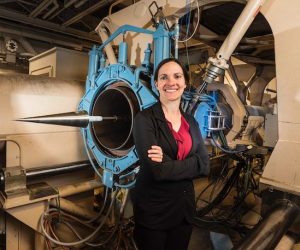

Feature image: Implicit gender biases create barriers for women studying and working in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Source: Pixabay CC0