Amanda Maxwell, Science Borealis editorial coordinator

What image pops into your head when you hear the word ‘expert’ in news stories? It’s probably the stereotypic male authority. ‘Probably’ because globally women’s voices are missing from the news – we’re much more likely to hear and see men quoted as experts.

Recognizing media bias is one thing, but measuring the gender gap to inspire change is another. The Gender Gap Tracker could solve this problem and give women the voice they’ve been missing in the news.

Why measure missing voices?

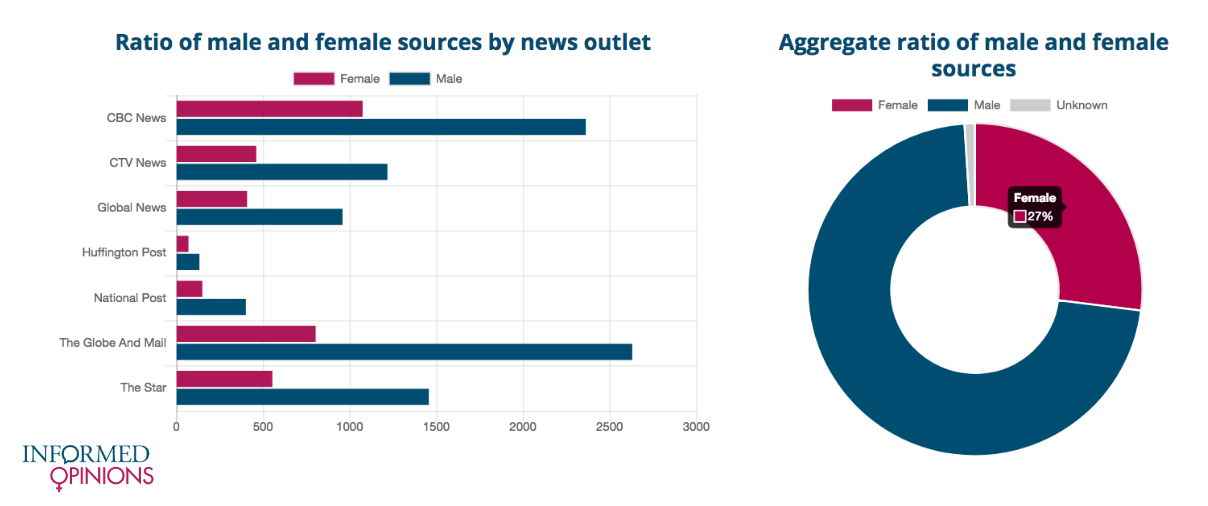

Despite population parity between the sexes, there’s a global gender imbalance in terms of media representation. Who Makes The News, an organization that manually tracks media representation, shows that women’s voices are missing: for every four people interviewed, seen, or mentioned in the news, only one is a woman.

According to a research paper for Informed Opinions, an ongoing Media Watch project promoting women’s voices in the news, only 29 per cent of Canadian news stories quoted women as a source. And this has consequences: “When significantly more men are represented than women, whether as experts, in “streeters”, or in audience feedback, the likelihood is that the perspectives of the entire population are being misrepresented, calling into question the quality of the journalism.”

This is worrying for many reasons. Apart from issues such as the lack of role models stifling career choices, missing voices impact diversity; when a group isn’t at the table, it’s easy to ignore or misrepresent an entire demographic.

“We can’t solve the complex challenges we face if we’re only drawing on the perspectives of half the population,” states Shari Graydon, founder and catalyst of Informed Opinions, and president of Media Watch. To correct this, the missing voices need to be recognized. According to Graydon, “What get’s measured, gets done.”

A gender gap tracking tool that searches the news

The Gender Gap Tracker (GGT) automates linguistic analysis of media content. Released in February, it’s the result of collaboration between Simon Fraser University’s Discourse Lab, the University of Alberta’s Digital Humanities Lab, and Informed Opinions. Dr. Maite Taboada, a professor in Linguistics who heads the Discourse Lab, gave a peek into the science ‘under the hood’ during a recent presentation.

GGT runs a daily scrape of content from numerous media outlets to search for quotes. After saving them to a database alongside metadata on the author, date and full text, the software then parses the text to isolate and identify quotes and their origin. This Named Entity Recognition approach uses open source software, SpaCy, which labels text as people, place or organisation. Software developed by the Discourse Lab extracts and defines the quotes before another open source software program constructs a syntactic tree to parse and search. Each quote is further analyzed to show the number of tokens (for example, word count). Finally, the gender of the person quoted is defined, using either an online service or by comparison with GGT’s growing cache.

Reflecting its reliance on open source software, GGT makes its programs available through GitHub, although data are only available to researchers to protect privacy.

The end result, described by Informed Opinions as “using big data to motivate media and amplify women’s voices”, could automate media monitoring for faster insight into the gender imbalances in Canadian reporting. Results so far show that only around 26 per cent of quotes in the Canadian media come from women.

Future direction for gap tracking

Work is already underway for GGT to analyze Canada’s French media. There’s also potential for looking deeper into quotes for the relationship between topics and gender, differences in space given to quotes, tone, and the status of who is quoted – victim, witness, expert, or policymaker.

According to Taboada, “We are interested in whether women are quoted mostly on certain topics. In other words, do we only hear from women when we discuss work-life balance or reproductive rights? And how are women portrayed in those situations? Are they experts or just general sources?”

Diversity of voices is another potential research topic, looking at gaps in representation from people of colour, racial groups, and so on. For this, Taboada is hopeful. “When working on gender equity, other forms of diversity often follow.”

Furthermore, the analytical underpinnings of the GGT could help mine big data in the future because, as noted by Taboada, most big data is in language form.

Why mind the gender gap?

Fewer fuzzy-haired Einstein lookalikes in science illustrations and comedy skits would be wonderful, but there is a more serious message to consider here. Fewer women experts in the news reduces female visibility. While the GGT did not specifically address women experts in science reporting, we already know that there is a gender gap affecting STEM:

- The Draw A Scientist study in elementary school students between 1966 and 1973, found that only 28 out of almost 5,000 drawings showed women (~0.6 per cent).

- The funding disparity for women scientists, as reported in The Lancet, suggests that women are not seen as expert enough to get the grants.

- Missing voices might also contribute to STEM’s ‘leaky pipeline’ – Not only do women receive less funding, but their numbers decrease progressively with each career stage.

Do we know if missing voices result in fewer role models to inspire girls to choose science, or encourage grant-awarding bodies to pass over women as experts? Although there is no direct evidence linking missing voices to disproportional representation, the Draw A Scientist study mentioned earlier suggests it does: with increasing visibility of women in science since 1973, around 28% of children now draw a female scientist.

How to mind the gender gap as science communicators and writers

Informed Opinions hopes the GGT spreads awareness, inspiring media companies to bridge the gender gap once they see how bad it is.

Men are used as expert resources by the news media far more than women. Source: Informed Opinion – used with permission

However, news reporters and communicators also share responsibility for correcting the gender gap. We need to balance the voices by actively selecting women as experts.

Bloomberg is taking this approach, with journalist Ben Bartenstein taking action to correct his own gender gap stats. He’s boosted the number of women experts quoted in his stories from a dismal 13 per cent in 2017 to around half in 2018.

Science writer Ed Yong is also taking a proactive approach and shows that it works. According to Yong:

“Skeptics might argue that I needn’t bother, as my work was just reflecting the present state of science. But I don’t buy that journalism should act simply as society’s mirror. Yes, it tells us about the world as it is, but it also pushes us toward a world that could be. It is about speaking truth to power, giving voice to the voiceless. And it is a profession that actively benefits from seeking out fresh perspectives and voices, instead of simply asking the same small cadre of well-trod names for their opinions.”

Women may be more reluctant to agree to interview requests, but if we’re not asking them, they’ll continue to be drowned out by male voices. And if that happens, we all lose.

Resources

- The 500 Women Scientists platform holds a multidisciplinary network of women scientists available as experts .

- Informed Opinions also has a database of over 900 diverse, qualified women in all fields (hundreds in science) who are ready to say ‘yes’ when media call.

~30~

Disclosure

Amanda Maxwell works as a communications coordinator in Simon Fraser University’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. She was not involved in the Gender Gap Tracker project.

Banner Image

Making sure women’s voices are heard in the media. Here, the Female Food Heroes competition works closely with the media to try and raise women’s voices. The aim is to make average citizens more aware of the women who produce the food they eat, and the challenges that these women face. Oxfam East Africa CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons