by Raechel Bonomo, guest contributor

As I spend most of my free time outdoors, I’ve been fortunate enough to see many great examples of Canadian nature. I have watched a family of deer feeding by a stream in Alberta, seen tracks of several elusive mammal species, such as porcupine and white-tailed deer, hiding in the depths of Ontario forests and witnessed glorious herons flying across a Nova Scotia skyline at sunset.

While there is beauty in nature, sometimes we see the less picturesque side of it. From the visible impacts of climate change and degradation on landscapes, to the hardships endured by the species that live there, nature’s struggles often present themselves in ways that can be hard to swallow.

The first time I saw a fish with whirling disease was while fishing at a friend’s cottage on vacation in Alberta. I didn’t fully understand what I was looking at. Peering down into the water from the boat’s edge, I saw what looked like a young salmon swimming in a lopsided circle. Its tail appeared to be a bit darker than salmon I had seen before. In the name of science, I plunged the large-handled net lying on the bottom of the boat into the water. My first thought was the fish was caught in some old fishing line or had a hook embedded in it.

Also unlike most salmon, which are very quick swimmers especially when they’re alerted to a potential predator, this fish was fairly easy to scoop up. While my friend leaned over the side of the boat to fill up a large bucket with lake water, I slowly lifted the fish out of the water. Once safely in the bucket, I had a better look at it. No line and no hook, but I had to find the sinker in question.

I pulled out my phone and searched our new passenger’s symptoms, WebMD-style. It didn’t take long to diagnose the fish, and with a disease as aggressive as this one, the prognosis didn’t look good.

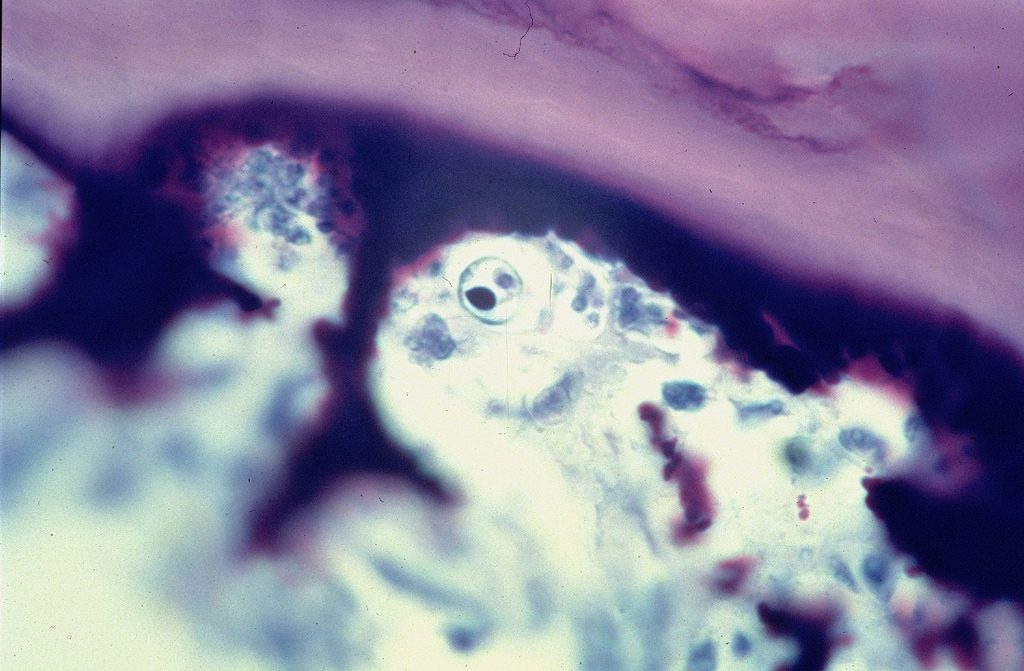

Whirling disease is caused by Myxobolus cerebralis, an invasive parasite from Eurasia. The parasite is known to inhabit the head and spine of fish from the salmonid family. This includes trout, whitefish and, in this case, salmon. Once in the fish, the parasite quickly multiplies, creating pressure and throwing off the infected fish’s equilibrium. This impacts the fish’s ability to swim normally, causing it to swim in a “whirling” pattern. Infected fish also have difficulty feeding and avoiding predators due to their inability to swim effectively.

In addition to erratic swimming, infected fish may have a darkened tail and/or a deformed spine and head. In many cases, whirling disease can lead to death – especially in younger fish, as their softer cartilage makes it easier for the parasite to penetrate.

Whirling disease is caused by Myxobolus cerebralis, an invasive parasite from Eurasia. The parasite is known to inhabit the head and spine of fish from the salmonid family. This includes trout, whitefish and, in this case, salmon. Once in the fish, the parasite quickly multiplies, creating pressure and throwing off the infected fish’s equilibrium. This impacts the fish’s ability to swim normally, causing it to swim in a “whirling” pattern. Infected fish also have difficulty feeding and avoiding predators due to their inability to swim effectively.

In addition to erratic swimming, infected fish may have a darkened tail and/or a deformed spine and head. In many cases, whirling disease can lead to death – especially in younger fish, as their softer cartilage makes it easier for the parasite to penetrate.

But how did this disease get into our waters?

In Canada, whirling disease has impacted fish in several bodies of water in Alberta. To date, the infected areas include the Bow River, Oldman River, Red Deer River and, most recently, North Saskatchewan River. First found in Canada in 2016, this is considered a fairly new invasive disease here – and one we have the opportunity to stop.

Whirling disease is spread through tiny spores that occupy river bottoms. These spores are then consumed by aquatic tubifex worms. While inside the worm, the spores develop into a tubular aggregate myopathy (TAM) that is released into the water. These TAMs attach themselves to fish and work their way into the host’s body, moving toward its head. While near the host’s head, the TAM develops once more, into the parasite. After a few weeks, the infected fish will develop whirling disease symptoms. When the fish dies or is eaten by a predator, the spores are released (either by decay or through the predator’s waste), and the cycle continues.

Scary stuff, right?

While whirling disease isn’t harmful to humans, it’s detrimental to fish populations living in infected waters. Currently there is no cure for whirling disease. But, in the meantime, we can all do our part to stop its spread. This includes:

- not moving any infected live or dead fish;

- cleaning equipment (such as watercraft and fishing gear); or

- avoiding transferring contaminated water to another waterbody.

Any observations of whirling disease in fish should be reported to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. By spreading information about this disease, you can help protect Canadian fish.

~30~

This article originally appeared August 28, 2018, on Land Lines, the Nature Conservancy of Canada blog.

Raechel Bonomo, a member of the Nature Conservancy of Canada team since 2015, she can be found either running on or hiking through trails with her pug and partner-in-crime, Molly or cooking up something good in the kitchen (or over her preferred oven: a campfire).