Mary Anne Schoenhardt, Science & Society editor

The summer of 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, which is credited to the two Canadian scientists Frederick Banting and Charles Best. Insulin has saved the lives of millions of people who have diabetes. This discovery won the Noble Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1923 and is one of Canada’s best-known contributions to medicine.

The work done by Banting and Best was revolutionary for medical research and life-changing for people living with diabetes. But what were the context and process for this discovery, and is there any value in studying them?

Charles Best (left) and Frederick Banting (right) are best known for the lifesaving discovery of insulin. Original photo from Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, CC 2.0

Historical context

The history of science is a discipline that studies human knowledge production. It can include the study of relatively modern scientific advancements, such as insulin, as well as the knowledge of ancient societies. Science communicator Hank Green describes the history of science as more than just a story of humanity’s collective movement from ignorance to knowledge. Beyond telling the stories of people who have made great scientific discoveries, the history of science provides the context in which these discoveries occurred and can be understood.

To truly understand a historical event, you have to understand the context in which it took place. Science is no different, and the history of science helps to provide this understanding. While we endeavour to make science as objective as possible, funding and personal and societal perspectives will always introduce some bias into scientific work.

According to Dr. Sarah Symons, a science historian and professor at McMaster University, “You can’t really split [the history of science] away from [the] philosophy of science, or science policy, or science and society. I see them all together as perspectives on science.” All of these perspectives are crucial for understanding how information is created and disseminated. Without them, we have no context for understanding the bias that goes into producing science or interpreting the results that we see.

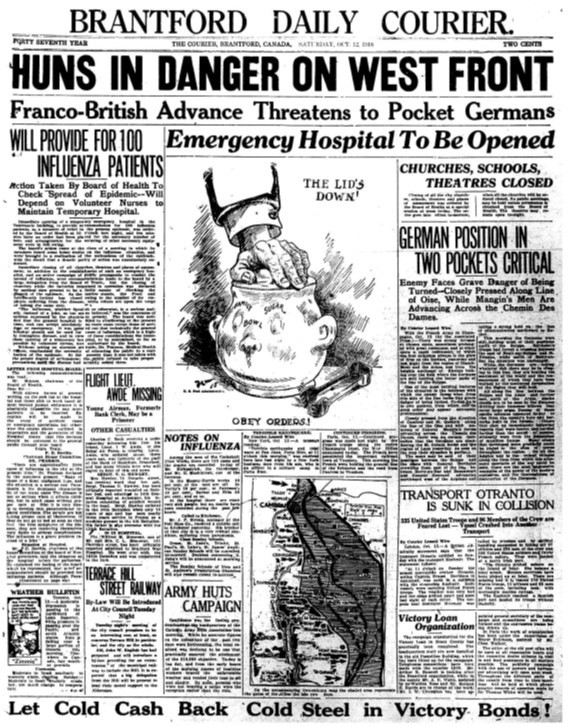

The history of science doesn’t just focus on the scientific advancements made but what influenced these advancements. While some of this information can come from scientific papers, archival documents such as newspapers can provide additional perspectives into these influences. This paper was published in 1918, three years before insulin was discovered. Photo from Ontario Archives, Brantford Daily Courier 1918. Public Domain

Science historians Naomi Oreskes (Harvard University) and Erik Conway (California Institute of Technology) have used a historical approach to science to provide a context for the origin of climate change denial. Through a review of the abstracts of 928 climate change papers and statements provided by all major American scientific groups of relevant disciplines, Oreskes found that none of them presented evidence against anthropogenic climate change. After further research into the origins of climate change denial, Oreskes and Conway found that a group of Cold War scientists equated environmentalism with socialism and saw their attack on climate science as a part of the fight against socialism. Using historical papers and the history of climate science, Oreskes countered ideologic attacks on modern climate science and communicated her findings to the public.

Forgotten research

Beyond the context that the history of science provides, it can help bring to light forgotten research. Science builds on past work. Research that may have been considered a failure in the past can provide crucial insights into current efforts. The history of science provides an account of research emphasizing the perspective of a scientist (rather than a philosopher or historian). This scientific perspective can provide a more specific and actionable guide to current study.

Other world views

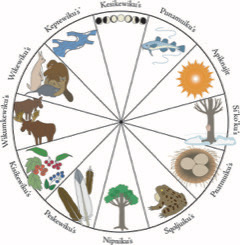

The Mi’kmaw calendar is based on the cycles of the moon, with each full moon (from the new moon before it to the new moon following it) being named after the season. These names describe what is happening in the environment at that time. Image from Mi’kmaw Moons. Used with permission.

The term scientist is less than 200 years old and encompasses only a small timeframe in human knowledge production. Studying the history of science reminds us that science isn’t the only way to understand something. A two-eyed seeing approach equally values two knowledge systems rather than privileging the western scientific view. The Mi’kmaw Moons project uses the two-eyed seeing approach, combining Mi’kmaw tradition and storytelling with western astronomy to teach about moon cycles and stars. By using knowledge systems other than modern science, this project allows a greater breadth of information to be communicated to a wider audience.

The perspective that the history of science provides is crucial for understanding today’s science-laden information. According to Symons, “Science is information handling, and we’ve never been exposed to more information than we are now. When I started doing [the] history of science, it was kind of restful. Now, it actually feels like it’s much more urgent to understand [the history of science]. It’s much more urgent for human beings to get some perspective… I think we need [a perspective on science] more than ever.”

Contribution vs. popularity

And what about the discovery of insulin? What can we learn from studying its history? While the discovery of insulin is commonly attributed to Fredrick Banting and Charles Best, equal credit should be given to John James Rickard Macleod and James Collip. Many medical historians believe that Banting and Best would not have been successful without Macleod and Collip’s contributions. A small group of Banting’s admirers believed that his and Best’s contributions were greater than Collip and Macleod’s efforts and promoted them in the media. Only from historical records do we see the significant contributions made by Collip and Macleod. Ultimately, Banting and Macleod shared the 1923 Noble Prize in Physiology and Medicine. Best and Collip were not named. The discovery of insulin is a reminder of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and the difficulties of attribution in science.

The history of science is the story of our pursuit of knowledge. It provides us with the context needed to understand this knowledge and to add to it. If humanity’s existence is an endless path from ignorance to knowledge, perhaps the history of science is the most important story of all.

~

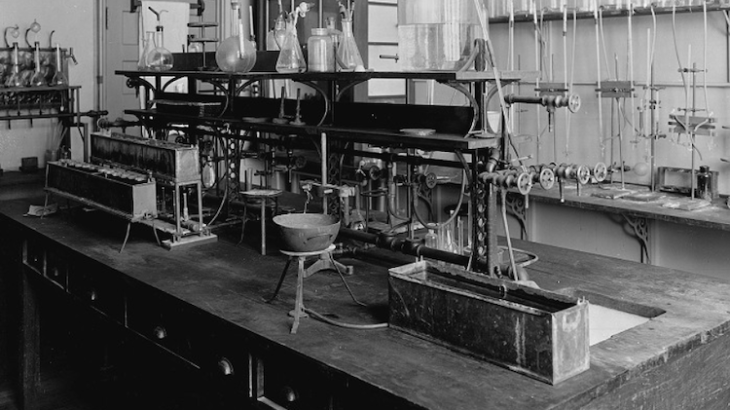

Banner image: Insulin was discovered in this University of Toronto laboratory. Photo from University of Toronto Archives. Public domain.