Jenna Finley, Biology & Life Science co-editor

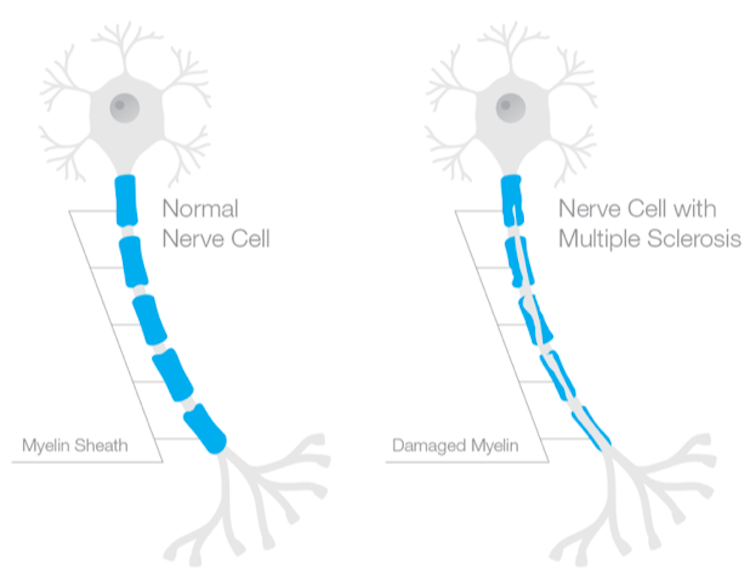

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease most people have heard of, but may not know much about. It’s classified as an autoimmune disease, which affects the central nervous system (CNS) – the brain and the spinal cord. It is the result of the immune cells in your body attacking the protective covering around your nerves, called the myelin sheath. This causes inflammation, and because the myelin helps deliver nerve impulses, damaging it can result in a loss of communication throughout the body.

The damage MS does to the CNS varies widely from person to person – no two patients are exactly the same. Some of the most common symptoms include:

- Limb numbness or weakness;

- Vision problems;

- Fatigue;

- Tingling; and

- Lack of coordination and/or unsteady gait and trembling.

There are many more.

As patients progress through the three identified stages of MS – relapsing-remitting (symptoms come and go), secondary progressive (worsening of symptoms), and primary progressive (worsening of symptoms with no remission) – symptoms can change and worsen.

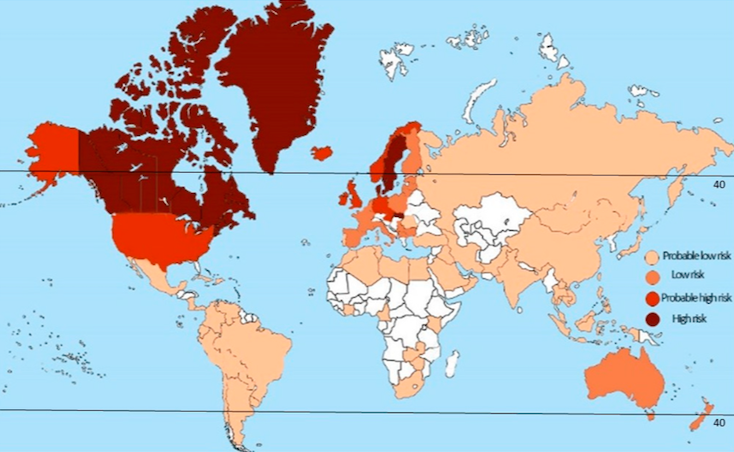

MS goes by another name in the medical community: Canada’s Disease. We have the highest rate of the disease in the world, at 290 cases per 100,000 people.

Why is the MS rate so high here? The answer: we don’t know. There are a lot of theories, the most talked about being the vitamin D hypothesis. It proposes a relationship between the lack of vitamin D that Canadians get – thanks to our long winters limiting our sunlight exposure – and the prevalence of MS in our country. Considering that MS rates tend to decrease the closer you get to the equator, the theory seems promising, but research is still ongoing. Other genetic, hormonal, and environmental theories have also been proposed.

Because the disease is relatively common here, it’s not surprising that we also lead the world in MS-related research. There are 32 clinical trials in Canada currently recruiting subjects and another 186 trials are ongoing. Canadian laboratories and clinical trials have spawned amazing breakthroughs. A recent study at the University of British Columbia found the genes that might be responsible for MS in families with multiple MS sufferers.

The first treatment for MS was made available in Canada in October of 1995. Today there are numerous treatment options for patients with MS, from disease-modifying therapies to symptom management, and more are being investigated every day.

The Ottawa Hospital MS Clinic is currently the only clinic in Canada to offer stem cell transplants to MS patients. The procedure involves destroying the entire immune and hematopoietic systems – leaving the patient without white cells or red cells – and then giving them an infusion of stem cells to regenerate the immune system. However, this treatment is very risky. The amount of chemo given to patients in the absence of a stem cell graft is considered lethal, which is why Dr. Mark Freedman, a professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa and the director of the Ottawa Hospital-General Campus’ Multiple Sclerosis Research Unit, hopes less invasive treatment options will become available soon.

With his team, Freedman is currently working on re-myelination research – repairing damaged myelin that allows patients to recover some lost function – as well as pursuing alternative research. However, he thinks that combination drug therapies – giving multiple complementary MS drugs to a single patient – are the future of MS treatment: “You can’t do it right now… [but] that’s been the past for many diseases. Look at all the other autoimmune diseases – lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease – … the average patient is on several different disease modifying drugs because they work [together].”

But while this may be the future, there are no current trials being done to pursue complementary drug research and that’s because of the high cost of MS drugs – no government agency or insurance company is willing to pay for more than one drug at a time. Because the first MS drugs weren’t available until 1995, drugs are only now reaching the point where they can be produced as generics, which severely slashes the price. However, until that happens, Freedman says “we’re stuck with one agent for one patient at one time.” And he points out that it’s not even clear that using multiple drugs is effective: “I’ve written several grants to try to do the [complementary drug] studies but nobody wants to fund them. Especially industry, they’d much rather sell you one drug for a lot of money.”

Having a variety of treatment options and medications available is critically important in diseases like MS because symptoms impact each patient differently, and medical treatment is never one-size-fits-all. So far, we have one generic MS drug in Canada: Glatect, a generic form of Copaxone, which works to produce immune cells that are less damaging to myelin. And while it’s still not cheap, it’s definitely much cheaper than Copaxone’s $16,241 per year price tag. Freedman hopes more drugs will become generic. That will open the doors to the previously impossible multi-drug trials.

The advent of new technologies means that treatment research now includes reversing the damage done to MS patients. Patients’ brains seem to attempt to repair themselves naturally, but often this process is incomplete or leaves the patient with some lingering deficit. Freedman thinks that since “the mechanisms are there in play” researchers might be able to exploit or strengthen them. This research is ongoing.

Once doctors like Freedman were counselled to not tell patients if they suspected they had MS because the disease was not understood and there was nothing that could be done. Now there are a variety of treatment options available and more being investigated every day. Canada remains at the forefront of MS research around the world, and the momentum continues with new studies.

~30~

Please check out The MS Society to learn more about the current research being done and/or make a donation to support MS research.