Amanda Maxwell, Science Borealis editorial coordinator

Writing about science is a great way to explore new subject areas and make cool discoveries. Often, you follow what interests you and get to tell everybody else what’s so fascinating about it. But sometimes, you find out things that aren’t so great. For example, who wants to learn that the infective dose for norovirus is a mere 20 virus particles? Compare this to the billion units sprayed out per gram of diarrhoea or aerosolized in vomit to bump up the ick factor. Although writing about food science is a little stomach-churning at times, it’s also a great opportunity to learn more about what ends up on your plate and in your mouth.

Meat glue was one such opportunity. Not only did I find out that this is how the food industry glues together bits of meat into hot dogs, ‘steaks’ and shrimp noodles, I also learned about food safety, federal legislation, and food fraud. So not quite frankenfoods, but – spoiler alert – you might run into it at your summer barbecue.

What is meat glue?

Meat glue does exactly what it sounds like it does: it sticks meat together. But instead of acting as an adhesive, meat glue, aka transglutaminase (TG or TGP on food labelling), creates bonds between proteins to fuse adjacent meat surfaces together.

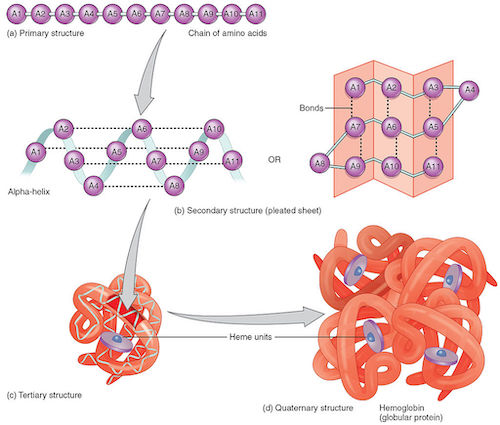

How peptide bonding forms protein structure. Image from OpenStax College CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Meat is mostly made up of proteins, which are chains of amino acids held together by peptide bonds to form polypeptides. Individual amino acids have side chains sticking off them that interact with each other.

Transglutaminase is an enzyme that acts as a catalyst to create bonds between individual amino acids. It binds the glutamine on one chain to the lysine on another. Simply sprinkle the TGA onto the surfaces of two meat samples, press them together and refrigerate. The resulting seam is almost undetectable and won’t tear apart.

Adam Melonas’s signature preparation is an edible floral center piece named the “Octopop”: a very low temperature cooked octopus fused using transglutaminase, dipped into an orange and saffron carrageenan gel and suspended on dill flower stalks. Image by Mikeanegus – Own work, Public Domain, Wikipedia

Why meat glue?

Molecular gastronomy – the art of applying scientific techniques to cooking – has embraced meat glue, with chefs using it in all sorts of weird and wonderful concoctions. How about octopop flowers as an edible centrepiece? It’s great for making meats stick together to make unexpected products such as shrimp noodles or a turkey-turkey-turkey sandwich. By extension, a streamlined turducken for Thanksgiving seems possible where slivers of the individual meats could be glued together into a neat loaf.

It’s also used for much more mundane reasons, such as sticking scraps of meat together to form larger portions, for improving texture in restructured poultry meat products, and to make sure certain emulsified meat products don’t fall apart. There’s a good overview of all meat glue’s uses here.

Who controls meat glue?

Federal oversight of what we put on our plates usually focuses on health, safety and awareness. So regulations usually ensure that producers stick to safe ingredients and use labelling to inform the consumer.

Designated as GRAS, or generally regarded as safe, TG used in food preparation usually comes from bacterial preparations rather than an animal origin. It’s very similar to the TG we produce in our own bodies during the blood-clotting cascade. Regardless of the source, federal food agencies often control its use in food. This applies regardless of how often a product is used, and for meat glue it’s not very often. For example, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) requires labelling to show that meat glue is present in products formed using meat binders. Likewise, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) does not consider meat glue as a processing aid that would be exempt from labelling requirements.

The European Commission Food and Safety Authority (EFSA) is developing a framework for formulating future regulations. A food enzyme would only appear on an approved list if:

- It does not pose a health concern to the consumer.

- There is a technological need.

- Its use does not mislead the consumer.

Note: The EU has banned a different type of meat glue, namely bovine or porcine thrombin and fibrinogen. These two proteins, which are present in the blood-clotting cascade, are no longer allowed in foods.

Meat glue – what’s the beef?

Distasteful as meat glue in food might seem, it is designated GRAS as a processingtechniqueto improve the quality, safety or aesthetics of the food. So, if it’s okay to chow down on a deli slice held together with the culinary equivalent of Elmer’s glue, is there a problem?

Well, maybe – and this is where regulation comes in. Using TG improperly could compromise health and safety, and can also allow unscrupulous operators to get away with fraud.

Meat glue acts on the surface of meat cuts. It can be used to glue irregular cuts together to form a more aesthetic version that’s easy to slice at a caterer’s carving station. However, the surface of a cut of meat can also be its most contaminated area. Gluing slabs together could bond harmful bacteria deep into the centre of the ‘constructed’ steak. Care must be taken to cook the whole ‘joint’ thoroughly. If a ‘constructed’ steak is served rare – seared only around its outer edges – what ends up on your plate might be more like a lab culture dish than fine cuisine. Even though this is only a potential risk, Health Canada proposed removing solid cut meats from the list of products approved to contain TG. It’s reassuring to note that Food Safety News reported in 2012 that no outbreaks of foodborne disease had been attributed to meat glue.

TG also helps turn one ‘species’ into another: for example, imitation crab meat or lobster tail is often finely minced Alaskan pollock or other white fish paste held together with meat glue. But it’s also (supposed to be) labelled so you know what you’re getting. However, unscrupulous operators can use these same techniques to defraud diners. It’s possible to glue cuts together to disguise low quality meats – is that really a prime beef fillet on the plate, or just the scrappy end of cow? Food fraud, where low-cost or low-quality products dilute, or substitute for, the genuine article is surprisingly common.

So how to avoid meat glue if you don’t like the idea of glued-together meat products? Since you can’t tell if meat glue is thereby looking at a cut of meat or a sausage, labelling is key. It’s very difficult to tell if it’s present, either deliberately or unintentionally, and restaurants are just as reliant as consumers on correct labelling.

While initially queasy about the whole concept, researching meat glue and food science writing in general has helped me understand how food is produced and kept safe to eat. It has certainly not put me off barbecues this summer.

Bon Appetit!

~30~

Banner image: Chicken-thigh terrine bound with transglutaminase. Image by H. Alexander Talbot (Flickr) CC BY 2.0Wikipedia Commons