by Alex Bond & Kasra Hassani

Biology & Life Sciences subject editors

At the age of 22, Charles Darwin embarked on what was to be a life-changing expedition from England on the HMS Beagle, as a companion to Captain FitzRoy. This voyage would lay the foundations for his theory of evolution, which was first published in 1859.

Darwin’s legacy lives on today, not only in the study of evolution – and of biology in general – but also in culture and art. Many celebrate Darwin Day on February 12 with special lectures or even Phylum Feasts!

This year, entomologists celebrated Darwin Day by naming a new rove beetle after both Darwin and humourist David Sedaris: Darwinilus sedarisi (here and here). Though Darwin originally collected the specimen on his Beagle voyage, only one other specimen of this species has ever been collected, and no new specimens have been collected since 1935. Much of the species’ natural habitat has been converted into agricultural land, and it is likely gone forever.

Over at Expiscor, Chris Buddle writes about the evolution of the Ichneumonidae, or parasitoid Hymenoptera. Parasitoids are parasites that end up actually consuming their host – a behaviour that’s been quite successful, evolutionarily speaking!

Darwin’s own take on the Ichneumonidae revealed much about how he reconciled evolution with the prevailing religious dogma of divine creation:

“But I own that I cannot see, as plainly as others do, & as I shd wish to do, evidence of design & beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent & omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidæ with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice. Not believing this, I see no necessity in the belief that the eye was expressly designed. On the other hand I cannot anyhow be contented to view this wonderful universe & especially the nature of man, & to conclude that everything is the result of brute force. I am inclined to look at everything as resulting from designed laws, with the details, whether good or bad, left to the working out of what we may call chance. Not that this notion at all satisfies me. I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect.”

Throughout his life, Darwin looked at the world as a giant network of relationships. In his ode to the Father of Modern Biology, Malcolm Campbell sums it up nicely:

“He saw the delight in everyday simplicity as well as the exotic.

In dog breeds found hearthside.

In pigeons bred for their feathered finery.

In the climbing vine.

In the movements of parasitic plants.

In earthworms.

In the wearing of rocks.

In the whorls of seashells.”

At the same time that Darwin was developing his theory of evolution by natural selection, though, another giant in 19th century science, Alfred Russell Wallace, was coming to the same conclusions. Unlike Darwin, who was the son of a doctor and grandson to famous pottery magnate Josiah Wedgewood, Wallace was decidedly working class, and often resorted to selling specimens to make ends meet. Wallace and Darwin corresponded, and even wrote a paper together the year before Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was first published.

Wallace wrote to Darwin about his ideas on evolution, asking him to pass them on to geologist Charles Lyell. However, many have claimed that Darwin held onto Wallace’s letter for two weeks so that he could revise his own work on the topic, and thus establish that he was the first to come up with the idea of evolution by natural selection.

Researchers used shipping records to trace Wallace’s letter to Darwin from its arrival in London back to its source on the island of Ternate, Indonesia, and found that Wallace had mailed his letter later than expected (here and here); thus both men are now recognized as coming up with the idea of evolution independently.

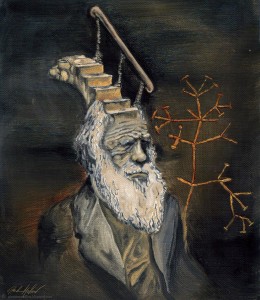

Darwin’s legacy transcends science: he’s also been the inspiration for works of art. The piece “Darwin Took Steps” by Glendon Mellow, appeared in The Eloquent Atheist on Darwin Day 2008. Mellow also wrote about the “evolution” of his work, calling the stairs leading from Darwin’s head “the path leading unexpectedly to DNA, beyond Darwin’s scope”.

“Darwin Took Steps”, oil on canvas, by Glendon Mellow, CC-BY-NC 3.0

Mellow also turned to Darwin when announcing the birth of his second son, Lochlan, in January of this year:

“The evolutionary legacy of an upright posture,

a clever mind

opposable thumbs,

acute visual sense,

a talent for pattern-finding

and a love of metaphor

Has been passed down through

an exploded star,

a planet,

life,

to chordates,

to mammals,

to apes,

to humans,

to Michelle and Glendon,

and finally, on January 20th 2014 at 9:20pm to Lochlan Charles Follett Mellow.”

*

Darwin’s birthday celebrations also coincided with a debate on evolution and creationism between noted science educator Bill Nye (The Science Guy) and Ken Ham, founder of the Creation Museum. You can watch the complete debate here. The general consensus around the internet is that Bill Nye won the debate (here and here). However, among the congratulatory posts praising Bill Nye’s dominance, Atif Kukaswadia at PLoS Blogs Sci-Ed expressed his fear that this debate – and others of its kind – might actually push moderate opinions and viewpoints to extremes rather than recruiting more people to the science side (provided that scientists always win). This could be dangerous for the future of science communication, but what else can be done?

Despite its universal acceptance in the scientific community, evolution remains a controversial topic. From the Scopes Trial in 1925, to current efforts by American lawmakers to make teaching evolution optional, Darwin’s idea of evolution by natural selection continues to induce cultural debate.

The Black Hole blog featured a guest post by Dr. Mark Larson on teaching evolution in the US. In response to a South Dakota bill that would prohibit reprimanding public school teachers who teach creationism, he writes:

“If one believes that a higher power is responsible and necessary for life as we know it, the fact that evolution provides a model where no intelligent agent is necessary can be extremely disconcerting. This is not the intent of science. Science’s only intent is to explain the unknown, and to follow the evidence wherever it may lead – separate from questions of meaning or purpose”

Thankfully, science is on stronger ground amongst the Canadian public, and teaching evolution is seen as less of a controversy. So as February draws to a close, let’s celebrate the founders of evolutionary biology, the amazing diversity of life, and our shared history with it.

2 thoughts on “Wrapping up February with Darwin”

Comments are closed.