Tanya Samman and Alina C. Fisher, Environmental and Earth Sciences editors

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we discussed findings that have given us fascinating new insights into the inner workings of dinosaurs and snapshots of dinosaur appearance, but dinosaur “mummies” are even more exciting and revealing.

“Mummies”

What exactly is a dinosaur “mummy”? When most people think of dinosaur fossils, they usually think of bones. “Mummies”, however, are dinosaur remains that preserve the exterior of the animal (e.g., skin, scales, armour) over large areas of the body, covering the bones, and resembling the carcass of a recently dead modern animal, only fossilized.

Let’s introduce you to three dinosaur “mummies”, including a spectacular three-dimensional specimen from Alberta.

Dakota

An extremely well-preserved hadrosaur (cf. Edmontosaurus sp.) was found in the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota (about 65 to 70 million years old). Nicknamed Dakota, this specimen contains mineralized skin, which has microscopic cell-like structures between five and 30 microns wide. Interestingly, the scales on the skin have a striped pattern, which in modern reptiles often means a change in colour.

According to Dr. Phil Manning, the presence of skin allows you to estimate the volume of muscle beneath allowing, you to calculate muscle energy, speed and strength of a dinosaur. One of the coolest things about this specimen is that it preserves what seems to be a hoof-like structure on its right front foot. Hadrosaur feet are usually reconstructed with individual toes.

Leonardo

Dakota is not the only well-preserved hadrosaur – there’s another one, a Brachylophosaurus called Leonardo from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana (around 75 to 78 million years old).

Researchers used radiography (popularly but incorrectly known as X-ray imaging) to peer into the fossil. They found evidence of a bird-like crop in the neck, and made images of its heart and liver (which are, admittedly, controversial). Physical and chemical analysis revealed the contents of its digestive system, including material from ferns, conifers, and magnolias.

Borealopelta markmitchelli

One of the most exciting dinosaur “mummies” comes from right here in Canada. This specimen of a 110-million-year-old nodosaur, a type of ankylosaur (armoured dinosaur), was found by chance in the Lower Cretaceous Clearwater Formation at Suncor Millennium Mine, Fort McMurray, Alberta, by excavator Shawn Funk.

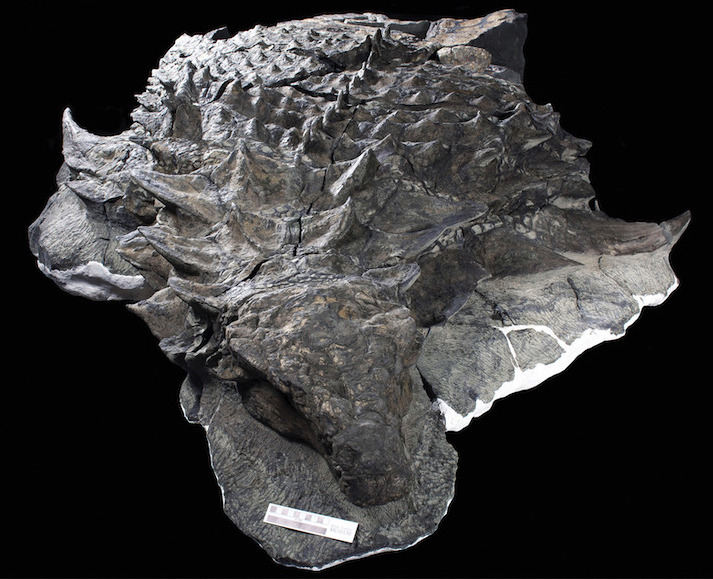

Sideview photograph of the holotype of Borealopelta markmitchelli, Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology (TMP) 2011.033.0001. Part of Figure 1, Brown et al. 2017 CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

“The specimen was a huge surprise,” says Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology Curator of Dinosaurs Dr. Don Henderson. “We knew from the first day we saw some isolated pieces on the floor of the Suncor firehall, that we had something exceptional. There had been a gentle trickle of nearly complete plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs since the 1990s from the tar sands, but to find a terrestrial dinosaur in the same [marine] rocks was completely unexpected.”

Henderson says getting the specimen out of the ground took a variety of equipment and the work of a large crew over almost two weeks.

“Before we could employ any heavy equipment to get the specimen out, we spent two days combing through the rubble to collect all the pieces shattered and scattered by the initial bucket hit,” he says. “Excavation then started with big excavators and over the next two weeks the machines and tools got smaller and smaller, ending with hammers and chisels. Large numbers of Suncor staff went out of their way to help us over the 17 days we were on site. Many university students on internships with Suncor had a nice day or two away from the office by helping us making plaster jackets during the final stages of the removal.”

Borealopelta markmitchelli, which translates as “Mark Mitchell’s northern shield”, was named in honour of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Technology technician who spent about 7,000 hours – almost six years! – painstakingly removing the rock encasing the specimen.

“Preparing the nodosaur was both exciting and challenging,” Mitchell describes his experience preparing the specimen. “I knew the specimen was exceptionally well-preserved based on the cross sections and counter pieces that were brought to the museum. I initially used large airscribes and zip guns to remove excess rock. I then switched to smaller airscribes and a pin vise to expose the bone/skin surface a few millimeters at a time. The combination of the hard rock and the soft powdery nature of the fossil bone, especially the osteoderms, made the preparation quite difficult. As the first completed pieces were placed together, the nodosaur began to take shape. This bolstered my enthusiasm to get started on the next piece of the specimen.”

When asked how he felt about the dinosaur’s name, he said, “Having the nodosaur named after me is a great honor”.

Face-on view photograph of the holotype of Borealopelta markmitchelli, Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology (TMP) 2011.033.0001. Part of Figure 1, Brown et al. 2017 CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

What is unique about this specimen is that it is three-dimensional and incredibly-life-like, unlike Dakota and Leonardo, which are flattened and withered looking. It was revealed to have abundant in situ (i.e., in life position) osteoderms (bones in the skin layer) with keratinous sheaths and scales preserved. In addition, its reddish-brown color and crypsis countershading that allowed it to avoid observation or detection by other animals indicates the strong predation pressure on this herbivorous dinosaur.

~30~

Banner image: People often think of dinosaur fossils as skeletons in rock or some kind of matrix and surrounded by plaster, like this Ornithomimus edmontonicus (Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology (TMP) 95.110.01). This specimen preserves a beak at the tips of its jaws, as described in Part 1 of this series. Photo by Tanya Samman