Jenna Finley, Biology & Life Sciences editor

On January 5, 2021, researchers at the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative and the universities of British Columbia, Carleton, and McGill released a ground-breaking study that expands our understanding of ecosystem services.

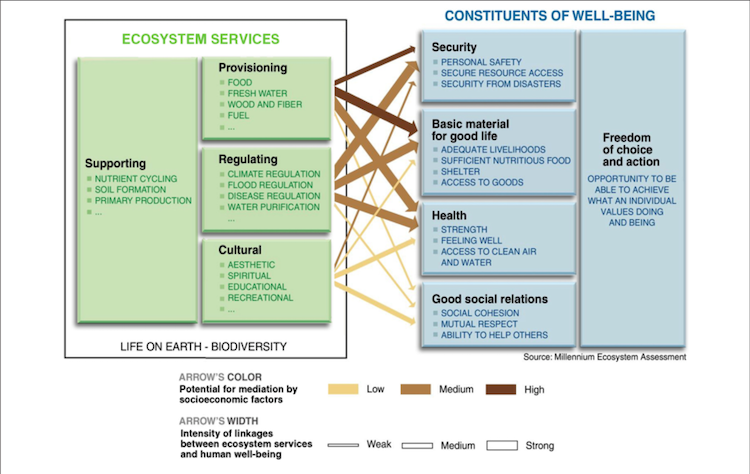

Ecosystem services are important but overlooked aspects of conservation and protection research. Ecosystem services are the benefits that humans gain from nature and the environment, both directly and indirectly. Examples of ecosystem services include carbon storage, recreation, and freshwater availability.

Initially, conservation and protection focused primarily on plants and animals. The shift to exploring and documenting the benefits that humans derive from an ecosystem began about 10 years ago. It is often erroneously assumed that ecosystem services research is about putting a dollar value on nature. What the field actually does is try to understand the benefits people get from nature and use this information to make better long-term decisions about conservation, protection, and development of the environment.

A diagram illustrating some of the connections between human well-being and ecosystem services, from Baveye et al. 2016. Image, CC BY

Typically, when a government is trying to identify a site for protection, it takes an area-based approach. This means that it weighs the ability of the ecosystem to provide a resource; this is referred to as the ecosystem’s capacity. Most parks and protected spaces that we enjoy today were designated through this method. However, there is evidence that this might not be the best approach to take.

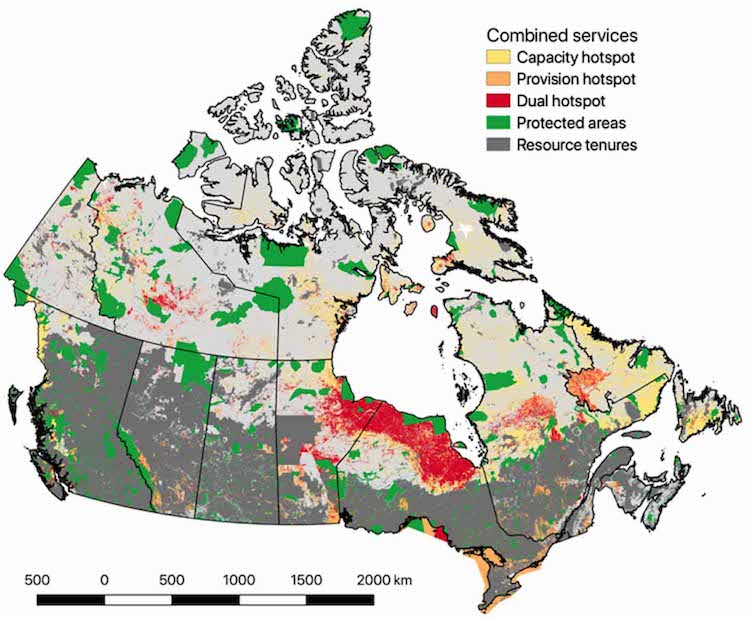

The evidence comes from the aforementioned study, which looks beyond the capacity approach. Dr. Aerin Jacob, one of the study’s authors, likens capacity to finding out “where the rain falls.” This new study focuses on provisions, or where capacity meets demand, and asks questions like “Who is actually benefiting? Where are those thirsty people?” By asking those types of questions and using primarily publicly available data, the researchers created a map of hotspots for certain ecosystem services including fresh water, carbon storage, and recreation.

Jacob hopes that a provisions-focused model will be used in future land use planning, so we make better long- and short-term decisions about using the land we live on and benefit from. Due to the limited availability of data, this model is not perfect. It could be improved by including more variables.

But according to Jacob, a comprehensive model wasn’t the goal. Instead, the model results are meant to give officials at every level of government something to work with.

In Canada, we don’t typically do a good job of collecting provisions information or making it publicly available, he says, but that doesn’t mean we aren’t able to make broad decisions now. The tendency for governments to drag their feet due to ‘not having enough data’ is a major concern for Jacob, who has a simple solution: “Use the information you have now to make the decisions that you can and get better information at the same time.”

Higher-resolution model output based on more comprehensive data would be great, but we can’t sit around and wait for it to appear. Scientists will never have every piece of data they want.

This research also found a disparity between currently protected areas and hotspots, with less than 15 per cent of provisions hotspots being protected. What’s even more concerning is that 50–66 per cent of the hotspots overlap with planned or current resource-extraction sites. Jacob says this “doesn’t mean the parks are in the wrong places. What it does mean is that we are going to be expanding protected areas in Canada and we need to be looking closely at how we are going to do that. We can’t only go after the low-hanging fruit.”

Ecosystem services capacity and provisions hotspots in Canada, and how those hotspots overlap with protected areas and resource tenures, from Mitchell et al. 2021. Map, CC BY 4.0

Canada has made many commitments over the last few decades to conserve and protect our ecosystem services and biodiversity. In the Kunming Agreement, we committed to protecting 30 per cent of our land and sea by 2030.

This is a lofty goal, especially following our commitment to the Aichi Targets 10 years ago to conserve and protect 17 per cent of our land and freshwater and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas.

I spoke to Jacob on New Year’s Eve. She told me the deadline for reaching Canada’s Aichi Target One was that night.

“We’re not going to make it,” she said.

This doesn’t mean that we can’t meet the Kunming goal, but it does require the government to change its current views on land protection and conservation. Jacob points out that “it’s difficult, but not impossible …. Now that we have the methods, let’s use them!” We need to make smarter decisions about which land we protect and redouble our resolve to protect it.

This idea is important as the federal and provincial governments slowly strip away protections from these areas. Some protected areas that are being exploited include vital provisions hotspots such as Alberta’s Eastern Slopes (open-pit coal mining), the Northeast Newfoundland Slope Closure Marine Refuge (BP Oil exploration), provincial parks in Alberta and Manitoba (large cuts and closures), and Ontario’s Duffin’s Creek Wetland (development of a distribution centre and production facility).

The good news is that we know public outcry can make a difference in these decisions. British Columbia removed 276 hectares of caribou protected land and old growth forest from development after severe public outcry.

“It shows that people care about these places,” Jacob says. “Advocacy works.”

Our natural ecosystems provide untold direct and indirect benefits to us every day, and they deserve more comprehensive protection than we are giving them now.

If you live in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, or Newfoundland, reach out to your local conservation authority and see what you can do to help. We have the resources to better identify and protect our ecosystem services. The last thing we should do is sell them to the highest bidder.

~