Dorottya Harangi, Health, Medicine and Veterinary Sciences editor

For my whole life, I’ve had it drilled into me to check for ticks after coming back from a hike or a long day outside. I never really understood why this was a big deal until I got older and learned about Lyme disease. So, what exactly is it? Lyme disease is a bacterial infection that is most often transmitted to people by ticks.

Ticks and Borrelia burgdorferi

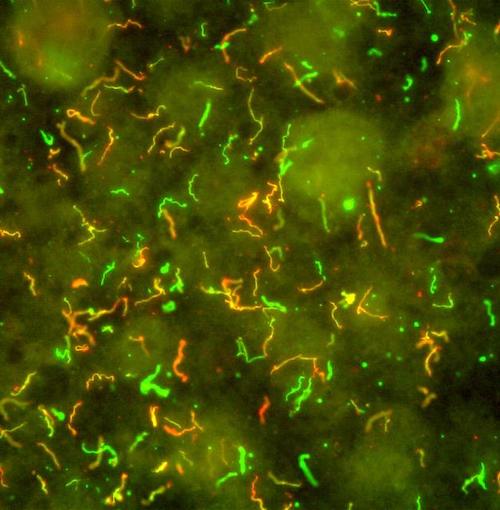

This scanning microscope image shows the Lyme disease bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi. The different colours indicate different surface proteins on the bacteria. Image by the National Institutes of Health, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

Lyme disease is typically associated with ticks, although a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi is really responsible for the disease. Ticks pick up the bacteria in their infant stage when they feed on an infected animal, typically small rodents such as mice. Once the infected tick bites you, this bacterium can get into different parts of your body. Depending on where it goes, Borrelia burgdorferi can affect many systems and organs, including your nervous system, brain, heart and muscles.

Not all ticks are capable of picking up and transmitting Lyme disease. The most common type of tick found in southeastern and central Canada is the blacklegged tick and in western Canada, it’s the western blacklegged tick. There are Lyme disease risk maps available for Canada that show where you are most likely to encounter ticks in each province.

The general guideline people use is the 24-hour rule – it takes about 24 hours for the bacterium to get into your system after you are bitten. However, it is important to note that this is not a hard and fast rule, and you can still get Lyme disease if the tick has been on you for a shorter time.

Signs and symptoms

The bulls-eye rash is associated with Lyme disease. Image by Hannah Garrison, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5

The symptoms of Lyme disease are often generic and can be associated with many different illnesses. Consequently, some people call Lyme disease the “Great Imitator”, which can make it difficult to diagnose. This ambiguity delays treatment and leaves patients confused and suffering.

Some of the most common Lyme disease symptoms include fever, chills, headache, fatigue and muscle and joint aches. Although many people get the characteristic bulls-eye rash, it is not universal and can vary in appearance from person to person. Some of the more severe, long-term symptoms of Lyme disease include facial palsy, arthritis and nerve pain.

If diagnosed in its early stage, doctors can treat the disease with antibiotics. Most of these patients make a full recovery.

Lyme disease in Canada

This increase is attributable to a variety of factors, with climate change being a primary driver. As air temperatures have increased, more ticks survive the winter, leading to a higher carry-over population in the spring. The most impacted areas in Canada include the southern regions of Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba, along with Nova Scotia. Other contributing factors to the increased prevalence of Lyme disease in Canada are the higher numbers and density of deer and small mammals, especially mice – the animals whose blood infects the ticks.

In response to the growing prevalence of Lyme disease in Canada, some researchers formed the Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network. The network aims to improve the research done on Lyme disease through a collaborative, team-based approach. They have established training programs for research trainees, and set up a seed grant program and patient biobank, among other initiatives. The Moriarty Lab at the University of Toronto is an example of a research lab focused on Lyme disease. The head of the lab, Dr. Tara Moriarty, is a member of the Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network.

Vaccine

You might ask why there is a vaccine against Lyme disease for dogs, but not for people? The answer is that there used to be one. Back in the 1990s and 2000s, there was a human vaccine, LYMErix, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline. Even though it was up to 90 per cent effective, the vaccine’s popularity waned due to a series of unfortunate events.

The uptake of the vaccine suffered from lawsuits and vaccine hesitancy, causing the number of people getting it to plummet. Even though there were no long-term adverse side effects, the manufacturer pulled the vaccine from the market for a variety of reasons. There are new vaccines in the early phases of clinical trials. Unfortunately, it will be a long time before there is a Lyme disease vaccine on the market.

~

Tips and tricks to avoid Lyme disease

Lyme disease may seem scary and overwhelming, but there are actions you can take to decrease your risk of contracting it. First and foremost, awareness of the disease is crucial. Educating yourself about what to watch out for is also important. Since it takes roughly 24 hours for a tick to embed itself in a person’s skin and transmit the bacteria, you should always check for ticks after spending time outside, especially if you have been in a high-risk area. Other tips include:

- Wearing light coloured clothing to spot ticks more easily

- Wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants so that ticks cannot easily make contact with your skin

- Spraying tick repellant on exposed areas of your body before going outside

- Walking on cleared paths instead of through underbrush or grass where there may be ticks

- Making sure to check your pets for ticks, since ticks in their fur can be passed to you

When it is undiagnosed, Lyme disease can have devastating effects on your quality of life. Fortunately, by taking a few simple precautions, you can avoid infection and enjoy the outdoors.

~

Banner image: A roadside sign design indicating ticks in the area. Image by 13smok, Pixabay, CC0