Harrison Brooks, New Science Communicator

Dr. Arinjay Banerjee stands outside of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan, where he took part in the ITraP program designed to re-define how students think about solving real-world problems using a collaborative approach. Photo by Harrison Brooks.

Newly minted doctor of virology Arinjay Banerjee has always been a gifted student. However, as happens with many graduate students, the way Banerjee thought about his research was flawed at its core. It wasn’t until 2014, when he came to the University of Saskatchewan that he realized it and changed.

That was the year Banerjee arrived in Canada and started his coronavirus research. It was also the year he joined the university’s Integrated Training Program in Infectious Disease, Food Safety and Public Policy (ITraP).

Funded by NSERC-CREATE, the program was initiated in 2013 by two USask researchers, Dr. Vikram Misra and former associate dean Baljit Singh of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine. Over the years, they had identified a major weakness in the way graduate students of every discipline were being taught, and sought to change it.

“They are very good at what they are being trained to do, which is research in their area of specialty,” says Misra. “The big deficiency is their ability to find synergies with other fields and collaborate with people from other disciplines.”

The two scientists considered many ideas on how a new program would look before deciding to bring together graduate students from any discipline to allow them to collaborate, using their own specific skillsets, to solve complex, real-world problems. The program they developed brought together all the aspects of One Health, a form of multidisciplinary, collaborative problem solving that brings together experts from every field to solve problems facing human, animal, and environmental health.

“Problems that involve the environment – ecological, cultural, economic, historical, et cetera – and those that live in it, including animals and humans, are complex,” says Misra. “To solve these problems, we need all of us with our differing expertise and experiences.”

This idea is the foundation of ITraP.

Running from 2013 to 2018 – the length of its funding – ITraP accepted 35 graduate students a year from any discipline, and consisted of two three-credit courses and an externship where the students could get real-world experience using their new skills.

For Banerjee, who joined the program’s second cohort, ITraP turned his thinking upside down.

Banerjee’s journey to ITraP

Banerjee always knew that he was going to be a virologist. Born in Calcutta, India, he chose this career path because of the close bond he shared with his grandfather, a pathologist who trained at the U.K.’s Royal College of Pathologists.

“Growing up, when I was visiting my grand[father], I would always be around his microscope because that’s what he had in his house,” says Banerjee. “He kept telling me, ‘You know, if you do microbiology, I’ll give you the microscope.’ Soas a kid, I always thought, ‘It’s got to be microbiology for me.’”

While enrolled at the National Institute of Virology in Pune, for his master’s, Banerjee met Dr. Misra at a virology conference at the Interdisciplinary Centre for Infection Biology and Immunity (ZIBI) summer symposium in Berlin. Inspired by the work Misra was presenting at the conference, Banerjee decided to continue his master’s research under Misra at USask, where he also joined the ITraP program.

“Arinjay struck me as a very intelligent and motivated person,” says Misra. “He completed his Master’s in my lab, which confirmed my impressions, and I suggested that he stay on for a PhD.”

Applying ITraP principles to research

Participating in the ITraP program challenged Banerjee to think outside of the box and beyond the walls of his lab. It brought concepts of community culture and social structure into the equation and forced Banerjee and his fellow students to account for messy social and human factors in their public health–related research and solutions.

“Classic example – 2014 Ebola outbreak. In my mind, I’m thinking I should go [to the outbreak], diagnose the problem, isolate the virus and make a vaccine – Boom, you’re done!” he says. “But now I know that it’s a lot more complicated.”

He says, “If you are going to understand the social structure [of a community] you need to have anthropologists and social scientists on your team, because all of your strategies will fail if the community refuses to vaccinate. For example, when a person dies in West Africa, the families touch the body and clean the body. You can’t go in there and tell them not to do that.” During earlier outbreaks of Ebola, some people ignored such advice.

“That is why you need sociologists that understand the social network and the culture.”

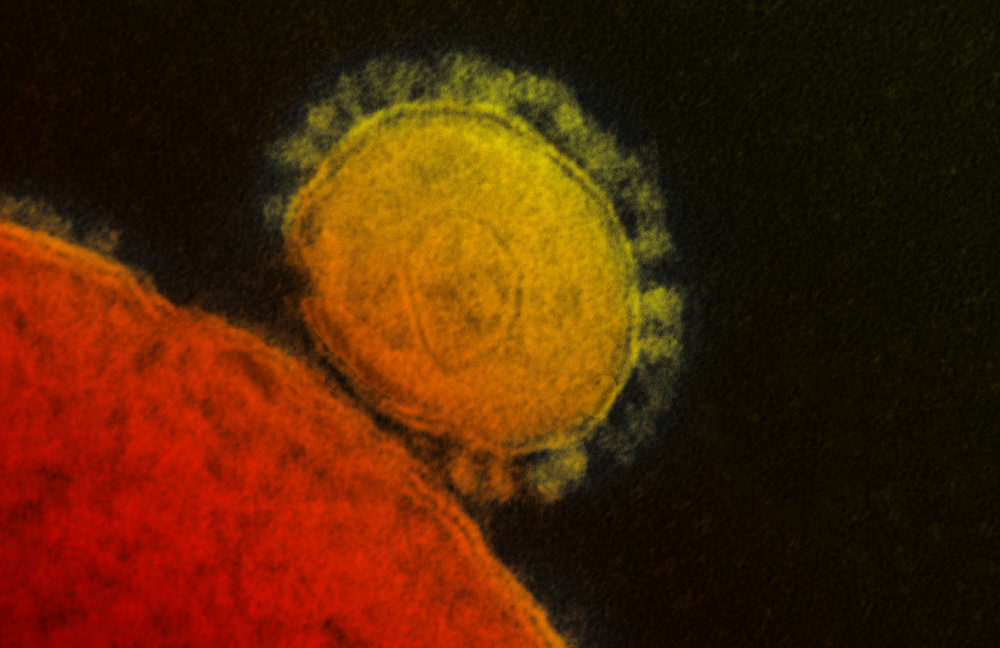

For his ITraP externship, Banerjee spent four months in Australia, sharing his knowledge of the bat coronavirus, which causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), with people who might come into contact with the disease during Hajj – an annual Muslim pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca.

The work led Banerjee to another important change in the way he thought. He realized that “you can publish all the high-impact research articles you want, but if you don’t make it accessible to the taxpayers then what’s really the point.”

Banerjee says, “I thought this was my way to make the information more accessible for people, and I think that’s what scientists should really work on.”

Next steps

When Banerjee finished the ITraP program, he continued to work as a course facilitator for the program’s next waves of students. Although the program’s funding finished last spring, Banerjee isn’t ready to let an idea this good disappear.

He moved to McMaster University in September to start post-doctorate research, and he is looking at bringing an ITraP-like, One Health program to his new school and eventually across Canada. He cites the U.S. One Health program, in which universities collaborate, as his model for what he’d like to see happen in Canada.

Ultimately, Banerjee wants more people to have the chance to learn the same valuable skills he was fortunate enough to learn through ITraP.

ITraP and the One Health process “opened my eyes to a whole lot of things that I would have otherwise never given a thought,” says Banerjee. “I think it is the only way to go in the future.”

~30~

Harrison Brooks is a journalism intern at the University of Saskatchewan. He wrote this post as part of Science Borealis’s Summer 2018 Pitch & Polish, a mentorship program that pairs students with one of our experienced editors to produce a polished piece of science writing.

Read more about Pitch and Polish and other New Science Communicators programs>

This month, we’ve been featuring works by our other Pitch and Polish graduates. Check out their posts:

January 7, 2019: Veterinary researchers seek clues to more effective treatment for deadly dog disease, by Nolan Chalifoux

January 14, 2019: Llama drama: Research into the mechanics of llama ovulation reveals a rare tumour, by Kylie Hutt

January 21, 2019: Small, deadly parasite emerging in Canada’s North, by Mila Bassil

January 28, 2019: Ramp walking helps diagnose lameness in dogs, by Emma Thomson