Abbas Mehrabian, guest contributor

There have been many discussions about the difficulties facing science journalism. “Crisis in science journalism #scicom21” by keatl, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

On November 9, 2020, when Pfizer and BioNTech announced their COVID-19 vaccine had a 90 per cent efficacy rate without publishing a peer-reviewed study to support their claim, many media outlets covered it as glorious news. Fox News’s headline “Pfizer vaccine proves 90% effective in latest trials” took the companies’ word for granted. Other news outlets such as Vox were more cautious and pointed out some caveats: that the results were from a press release, not a study, that they were based on just 94 cases of infection, and that the clinical trial wasn’t complete.

The role of science journalism is not only to explain the results of scientific studies to a general audience but also to help distinguish between well-supported and weak conclusions and examine possible conflicts of interest on the part of the scientists. When reporting on a study, a good science journalist provides context and explains how it fits within previous work in the field. “In an ideal world, science journalism will make science stronger by shining a light upon it,” says Maclean’s former science editor Kate Lunau.

Canadians are eager to learn more about science. More than 90 per cent of Canadians surveyed in 2013 said that they were interested in new scientific discoveries and technological developments.

However, bad science journalism risks undermining trust in science, says Chris Chambers, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Cardiff University.

There is no scientific consensus about the relationship between coffee and cancer. Photo by sfllaw, CC BY-SA 2.0

For example, scientific studies on the relationship between drinking coffee and cancer have produced inconsistent results, according to a 2020 article in BMC Cancer. Because of this inconsistency, science journalists must be careful when writing about the relationship between coffee and cancer. If they are not careful, Chambers says, “what you end up with is with 50 articles … saying that caffeine causes cancer and 50 saying that it cures cancer.”

Bad science journalism may be one reason that many people, including now-former U.S. President Donald Trump, don’t believe in climate change, or that only about half of 34,269 Americans surveyed in August 2020 said they would get vaccinated for COVID-19. In the U.S., distrust of science is so pronounced that health reporters Jamie Ducharme and Alice Park say one of President Joe Biden’s main challenges will be “restoring a nation’s trust in science.”

What are the roots of bad science journalism?

First, there is an inherent conflict between science and journalism. Media outlets compete for readers, and readers are attracted to short and exciting captions such as “A cure for cancer is found”, rather than lengthy, detailed sentences like “Scientists say a potential cure for certain types of cancer may have been found.” The media loves breaking news and revolutionary scientific discoveries which land stories on the cover page.

However, new discoveries often come with caveats, and it takes time to understand the whole picture. Take DDT, for example: for its discovery as a highly effective contact poison to kill pest insects, Swiss chemist Paul Müller was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1948. But then people noticed it had negative impacts on the environment, and in 1972 it was banned in the U.S. and in Canada.

DDT, once used extensively for pest control, was later found to be a threat to wildlife. 1955. Fort tri-motor spraying DDT. Western spruce budworm control project. Powder River control unit, Oregon. Photo by USDA Forest Service, CC BY 2.0; PDM (U.S.only) 1.0

In addition, reporters covering science stories don’t always have the training needed to understand the science deeply. As newsrooms have become smaller over the past few decades, they’ve laid off specialists – most reporters today are generalists. In 1989, over 90 newspapers in the U.S. had weekly science sections; by 2013, the number had dropped to 19. Moreover, a deep understanding of scientific studies requires time, which is hard to find in today’s busy newsrooms.

Finally, some scientists may struggle to clearly summarize their work for a general audience. They might find it difficult to avoid jargon, fail to illustrate their research with relatable examples, or simply not be particularly good storytellers.

So how can we produce good science journalism?

Well, there is no single formula for making good science journalists. They can be scientists who learn journalism, journalists who learn science, or scientists who pair up with journalists. All paths can lead to great science journalism. The most important tip for becoming a good journalist in any field is to be open to learning all the time, says Ivan Oransky, president of the Association of Health Care Journalists.

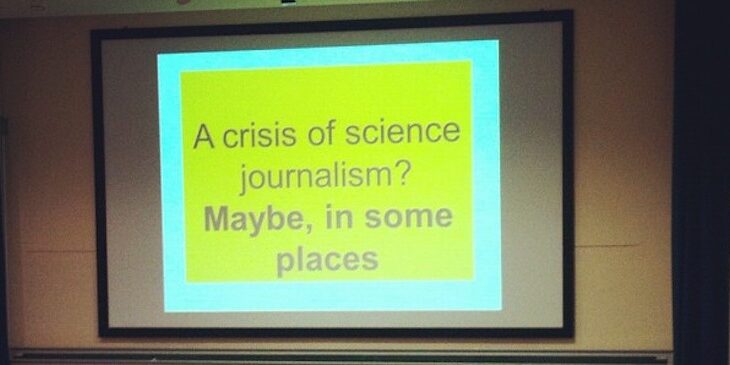

Some science journalists are scientists who learn storytelling as a technique to explain their research to the public. Take David Suzuki, who received a PhD in zoology and then started broadcasting on radio and television about science and the environment. In 2010, the Globe and Mail selected him as one of 25 transformational Canadians for his four-decade-old television series The Nature of Things.

David Suzuki, 84, has spent much of his life communicating science to audiences across Canada and the world. Here, he speaks on The Blue Dot Tour, in Vancouver, B.C., Canada. Photo by Kris Krug, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Not all science journalists have science degrees, but they all must spend time understanding science deeply. A prominent example is Bill McKibben, who started out as a business journalist and then became interested in the environment and wrote one of the first books about climate change for a general audience.

“Bill McKibben is the godfather of all the popular works of climate literature,” says Ross Gelbspan, former senior editor of The Boston Globe.

The third approach to science journalism involves partnerships between scientists and journalists. One successful example of this approach is Freakonomics, a 2005 book co-written by journalist Stephen Dubner and economist Steven Levitt, which sold over four million copies in four years and has been translated into 40 languages. The pair then started a podcast with the same name, which analyzes social problems through an economic lens. In 2012, it was named as one of the top 10 podcasts to “feed your brain” by Business Insider.

To produce better science journalism, we need more Suzukis, McKibbens, Dubners, and Levitts: creative people who can connect science and journalism by moving outside their educational framework and seeing the world through fresh lenses. According to Jo Marchant, a former editor for Nature and New Scientist, “[To write well about science,] you need a burning curiosity – about how the world works, what people are doing, why they are doing it, and why it matters.”

~

The role of science journalism help distinguish between well-supported and weak conclusions

I think journalism is growing up all around the world, especially in our country Iran

I think journalism is growing up all around the world, especially in our country Iran