Monsters of the prime

Who tare each other in their slime– Thomas C. Weston, “Untitled,”

Reminiscences among the rocks: in connection with the Geological Survey of Canada, 1889

~

Excavating fossilized dinosaur bones or permineralized leaves is something we expect from a palaeontologist; digging up poems about them, however, is new. PalaeoPoems is an online archival project with historical and modern poems about fossils, original palaeoart by guest artists, and details about the science behind each poem, and it’s shaping up to become a unique scicomm resource for palaeontology.

PalaeoPoems began when palaeontologist and palaeo-historian Brigid Christison was working on the early history of Canadian dinosaur hunters and found a “really terrible poem” in an 1800s memoir. (For more on the sometimes challenging relationship between poetry and science, check out this post by Lené Gary.) Over time, Brigid kept finding similar poems and wanted to share them. With a small team comprising Katrin Emery (logo, portrait illustration, graphic design), Mike Thompson (natural history writing), and Christina Muxlow (website design), Brigid created a monthly blog called PalaeoPoems.

Every post includes a palaeontology-themed poem (or two), followed by an audio recording of the poem, a related work of palaeoart, a discourse on the natural history of the poem’s subject, biographical information about the author (along with a portrait), and a list of further reading material. A poem could be about an extinct animal, tracing botanical evolution, or how a fossil came to be. Written by people with affiliations to palaeontology, the poems don’t shy away from using scientific jargon or emotionally expressive language and often employ humour.

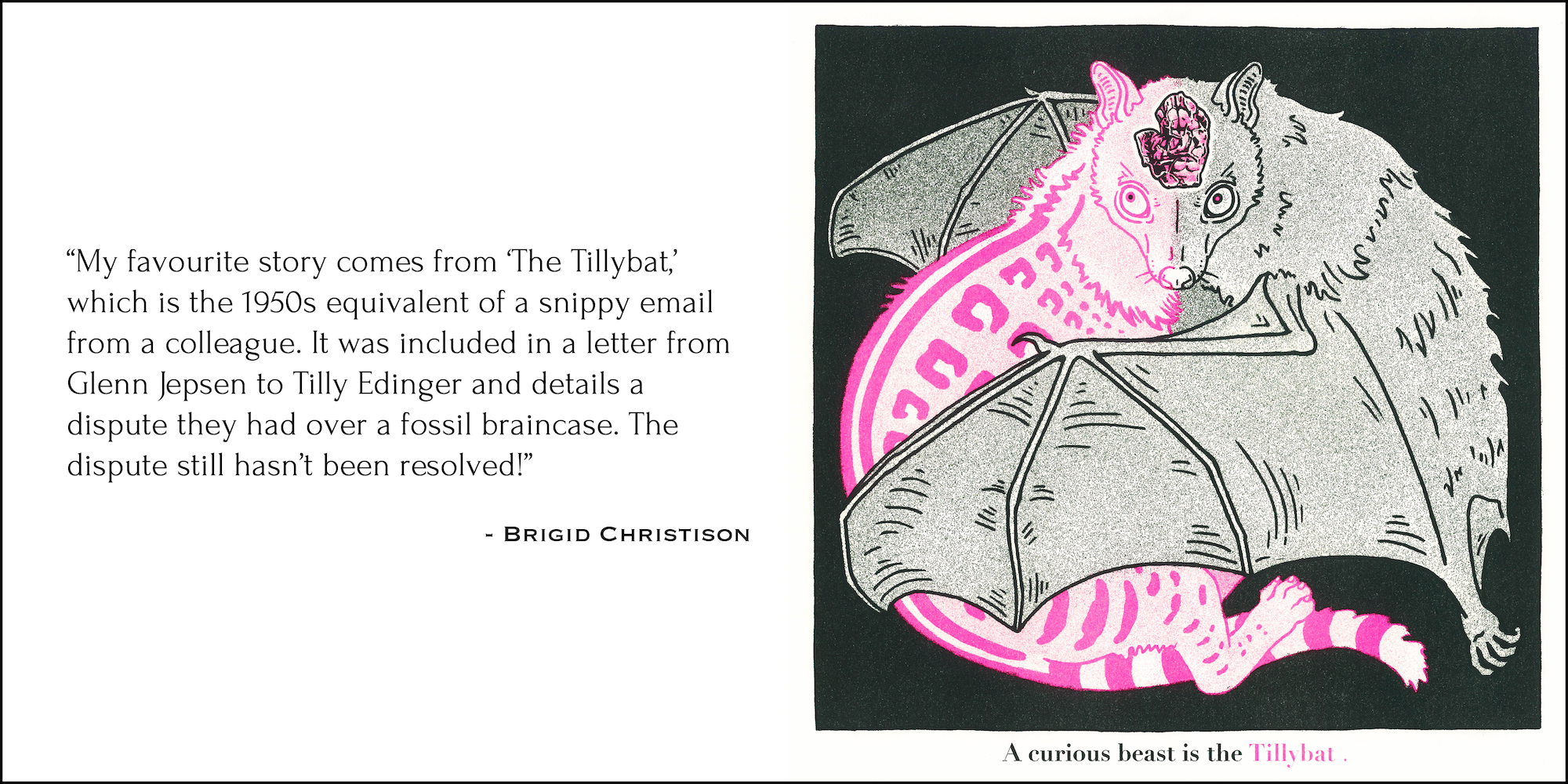

Artwork by Greer Stothers (Twitter: @GreerStothers; Website: greerstothers.com/) for “The Tilly-bat” by Glenn Jepsen. Image courtesy of PalaeoPoems.com.

Once Christison finds a poem, a guest artist produces a visual accompaniment. “We choose to include guest art because it can help folks imagine the creatures each poem was written about,” Emery explains, “and highlighting a variety of artists brings our community closer together.”

The range of artistic styles and media also demonstrates the flexibility of palaeoart, which tends to be seen as a rigorous practice due to the scientific demands of accurate visualizations of the past.

Palaeopoems and palaeoart also show similar historical tendencies.

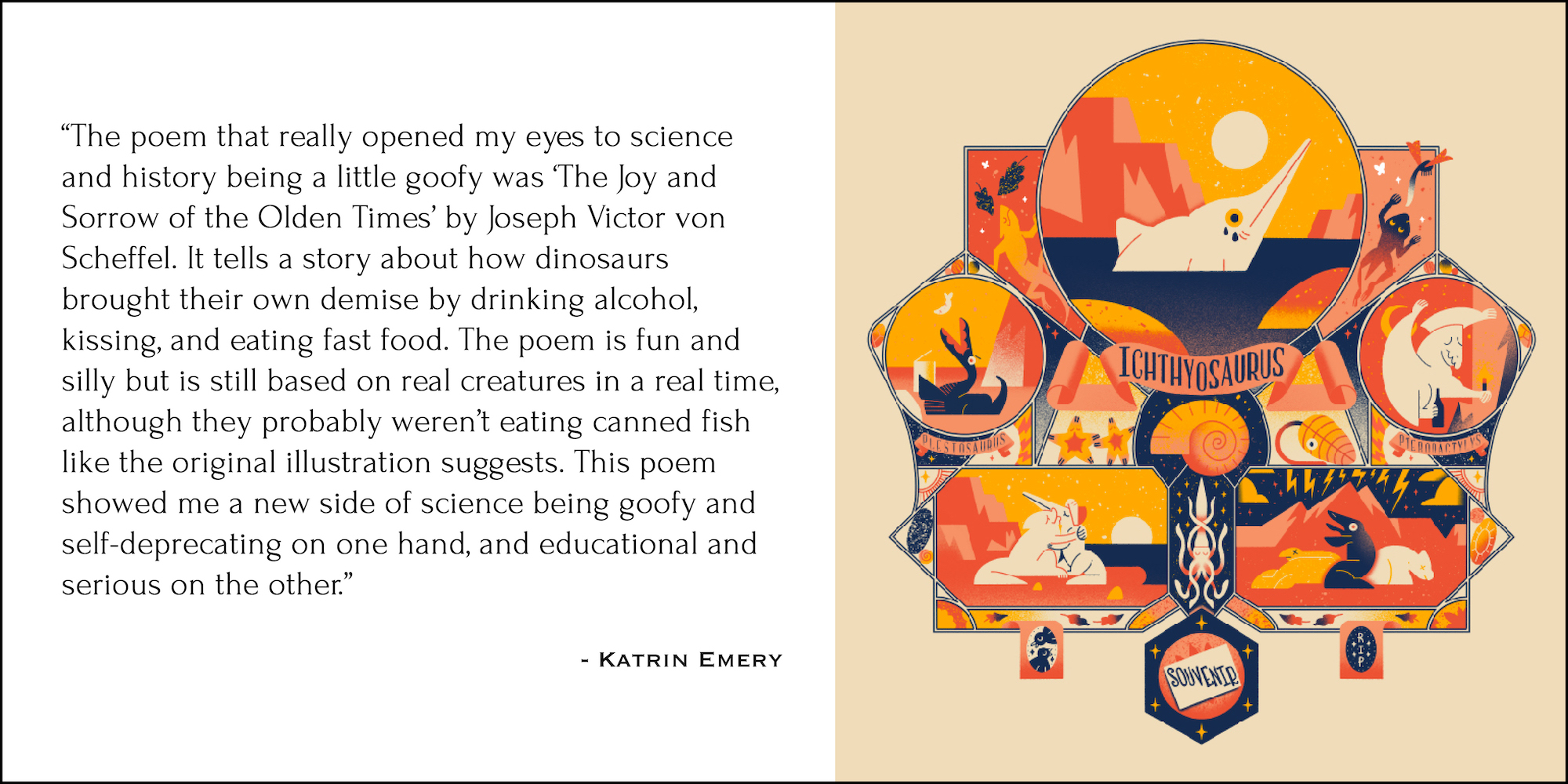

“The way the language in these poems has changed and the way palaeoart has changed mirror one another,” Thompson says. “Historical poems portrayed fossil organisms most often as monstrous, primitive and separated from modern organisms because they were ‘evolutionary failures’… Palaeoart of the time those poems were written also seems to reflect such things, where prehistoric life is made to look monstrous and often not like an actual living creature would have.”

Nowadays, the approach tends to be a little less dogmatic. “Modern poems are plenty dramatic and exciting,” he says, “but like with modern palaeoart, the excitement and drama comes from how modern science shows us just how weird and outlandish organisms already are in reality.”

Each palaeopoem undergoes a round of fact-checking. Launching off Wikipedia, Thompson goes through academic research and articles by science journalists to cover the natural history of a poem’s subject for a general readership.

“[I]t allows me to strike a good balance between academic and popular science writing and produces references for further reading that will cater to as many people as possible,” says Thompson.

Artwork by Dr. Hillary Maddin (Website: maddinlab.com; Twitter: @Evo_Deva) for “In Aid of Jamoytius” by Nancy P. Morris. Image courtesy of PalaeoPoems.com.

Sometimes Christison comes across poems with racist or otherwise inappropriate content or written by people with outdated points of view. Rather than erasing them, PalaeoPoems issues content warnings and tries to explain the content.

“In palaeontology,” Christison notes, “there’s the added element of evolution being used to ‘prove’ racial differences and, thus, white supremacy. Even today, papers will still pop up claiming to track the evolutionary history of race, and these are invariably extremely racist.”

Diverse ethnic representation in this field can be challenging, given the history of the field. “Though there have always been BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) and AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) palaeontologists,” Christison says, “finding work by them, let alone obscure work like poetry, is almost impossible. Their writings simply haven’t been preserved or made available to the same degree as white scholars.” She adds, “Palaeontology remains one of the whitest scientific fields today.”

Besides producing the main blog, the team also takes to Twitter with a #PalaeoPoemsPrompt every Friday to cultivate more modern fossil poetry. They have received unexpected responses. Thompson reveals: “You’d think it would be the more dinosaur-centric prompts, but honestly they don’t get more traction than any other topic. This has been a fun surprise, as we get to see a pretty big diversity of topics from our prompts.”

Artwork by Katrin Emery (Website: kemery.ca Instagram: @earth.sister Twitter: @KatrinEmery) for “The Joy and Sorrow of the Olden Times” by J. V. von Scheffel. Image courtesy of PalaeoPoems.com.

This two-pronged approach of sharing and inspiring the writing of palaeopoetry gives weight to PalaeoPoems’ mission to be a valuable participant in the field of palaeontology. At last year’s ComSciConCAN, a series of workshops by and for graduate students focused on the communication of complex and technical concepts, they presented the topic “Why study PalaeoPoems?”, where they championed poetry’s accessible language and ability to deliver insights that are both informative and palpable. Christison says, “Right now, we’re focussing on building our audience and especially on getting academics to consider PalaeoPoems as a legitimate form of science communication.”

Poetry offers a freedom in structure and style not found in journal articles. A lot can be understood from a short, carefully worded stanza. Whether or not PalaeoPoems succeeds partly depends on palaeontology-minded folx putting pen to paper.

If one of their Twitter prompts speaks to you, give it a try! The study of fossils will be richer for them.

~

Featured image: Artwork by Katrin Emery (Website: kemery.ca Instagram: @earth.sister Twitter: @KatrinEmery) for “Untitled” by Thomas C. Weston. Image courtesy of PalaeoPoems.com.

Poem links:

“The Tilly-bat” by Glenn Jepsen

“In Aid of Jamoytius” by Nancy P. Morris

“The Joy and Sorrow of the Olden Times” by J. V. von Scheffel