By Ann Yang, guest editor

We have been raised to see rage as something negative. We were punished for our tantrums, forced to endure “time outs” in our rooms until we were calm and collected. But is rage truly a bad thing? Can we tap into the untold power of rage to create positive change?

A wealth of research provides surprising answers to these questions. A “no” to the first one, and a hard “yes” for the second. In this blog post, I dive into the overlooked benefits of rage for science communicators and their audiences.

People are motivated by emotions and values

Many researchers believe cold, logical, evidence is what motivates people. That is very rarely the case. In fact, most people are mainly driven by emotions and instinct. You did not decide to buy a cookie because you carefully weighed all possible pros and cons. You decided to buy a cookie because you wanted to and were craving it (despite your New Year’s resolution to eat healthier!).

People are primarily driven by their intuition (the elephant) first and reasoning (the rider) second. Catering to a person’s values and feelings will be more effective than providing cold evidence. Photo: Sasin Tipchai on Pixabay.

Jonathan Haidt uses the analogy of an elephant and rider to describe the decision-making process. The elephant is your instinct: large, strong, and charging head-first into situations. It rarely listens to anything other than feelings and values. The rider is your logical reasoning: he guides the elephant’s actions. Only when someone considers logical arguments with sufficient time and attention, can the rider nudge the elephant towards a desirable destination. For you, as a science communicator, this means that changing the opinion of the elephant is going to take more than facts and information. It also requires considering what emotions and values your message might spark. This is why things may change very little even when evidence is clear and abundant. When people are not outraged enough—not enough people, not enough rage—the elephant isn’t motivated to move toward change.

Climate change is a case in point. The actual risk of climate change to our health is high—high enough that we should be alarmed. But on an emotional level, it can’t compete with events that are, on a practical level, far less important. Remember the riot in downtown Vancouver in 2011 when the Canucks were defeated in the Stanley Cup finals? People are simply not engaged with climate change on the same level as they are with their sports team. Climate change has little to do with Canadian pride (unlike hockey). It has even less to do with the motivating feeling of belonging in a group and opposing an external group (again, unlike hockey). No matter how much experts talk about the risks on TV, many people do not perceive climate change as an urgent and important risk that challenges their moral values.

So, to motivate action, we must provoke these emotions.

Converting rage into real action

Rage is an emotional response to unfairness and this response can be healthy and useful. It is an indicator that “something went wrong” and “it should not have happened like this.” In civil movements, rage is a motivation and a catalyst to push for change. It fuels people’s desire to rebel against injustice and the system that allowed the injustice to happen. To spark the flame of rage is to stoke the burning of passion.

For science communicators, that means we can use rage to create impactful change. By seizing relevant opportunities and strategically planning communication, we can spark a (useful) emotional “flame” within audience members.

Capitalizing on current events is one way to highlight the relevance and urgency of overlooked risks. Timely messages are more likely to capture public attention. However, the information presented must still be accurate and based on existing evidence. Otherwise, you risk spreading misinformation that could undermine your credibility and damage audience trust. Inaccurate information can also cause unintended harm.

To tailor your message, recall that emotions and values (the elephant) drive people. Consider what values matter most to your audience: harm, fairness, freedom, or something else? Plan your message to align with these values, making the issue morally relevant.

Showcasing real-life stories is another strategy. Stories of injustice can personalize the problem and add fuel to the flame that will ultimately drive action.

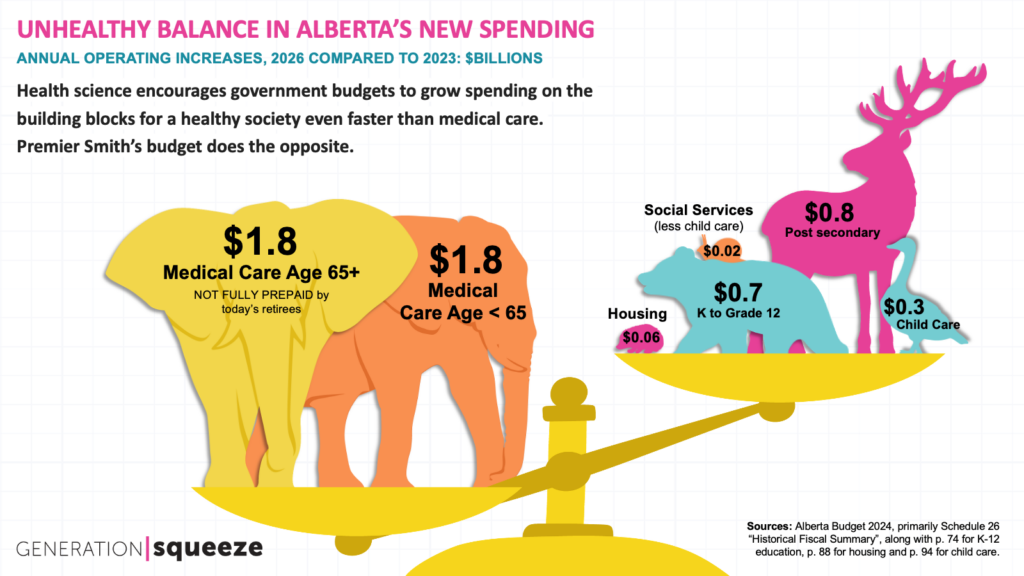

Visuals matter, too. A good picture (or video) speaks a thousand words. Pair your message with powerful visuals to make a long-lasting impression. Consider the Generation Squeeze case. The organization wanted to show that Alberta’s new governmental budget focused too much on medical care. To do so, it aligned its key message with a powerful graphic (see below). The elephants in the graphic represent budget increase in medical care. The smaller animals represent other types of spending growth (education, childcare, housing, and social services). Looking at the image, readers can immediately understand that the attention on medical care heavily outweighs all other spending. But it is also important to make sure that the image is understood in its context, otherwise it can be open to misinterpretation and abuse.

Visuals are powerful. Utilize images or videos to spark emotions and values. They can also be used to translate evidence into easily digestible, memorable, and shareable pieces. Image: Generation Squeeze.

Lastly, help people turn all that stirred-up emotion into real action. Provide clear and actionable steps. For example, encourage your audience to sign a petition, attend an event, or support a specific initiative. Rage without a channel for action can lead to frustration. Empowering people to take concrete steps helps them transmit their energy into meaningful change.

Match the outrage to the risk

Engaging people’s emotions and values is an effective way to harness rage, but it isn’t always the best path forward. Generating outrage when there is little risk creates unnecessary anxiety and fear. It is paralyzing and draws attention away from the things that really matter. For example, in 2023, WHO announced that aspartame may “possibly” cause cancer. However, the actual risk to health is low. Still, anxiety and fear ensued. News outlets like CBC, Scientific American, and the New York Times eventually stepped up to calm the public.

In other words, as communicators, we don’t want to cause unnecessary panic about small risks. At the same time, for high-risk issues the public doesn’t already care about, like oil spills or climate change, we need to find ways to drum up more outrage.

The goal is to align the audiences’ level of outrage with the level of risk they face.

Anger as an advocacy tool

Just as fire, if controlled, can be a valuable tool, anger, when used with care, can create positive change. As science communicators, we can strategically fan the flickering flames of rage and turn burning passion into meaningful action.

Author bio: Ann Yang (she/her) is a Master of Public Health student at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Pursuing the Inclusion and Accessibility in Health Systems pathway of study, her academic and professional journey highlights her passion for public well-being and EDIA. Outside of academia, she is the Communication Lead of Kids Brain Health Network’s Policy Advocacy Research Training Committee and a member of the Professional Development Sub-Council within UBC Faculty of Land and Food Systems’ Young Alumni Council. Through these roles, she empowers student learners and fosters the growth of emerging leaders.

Feature Image: Rage is like a fire. Leaning how to generate and control rage will allow you to successfully spark real, positive action. Photo: Ronald Plett on Pixabay.