Rana Semaan, Science in Society editor

On June 7, 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug Aduhelm™ (aducanumab-avwa) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease under its accelerated approval pathway. I felt overjoyed and excited reading this news. I’d seen the disease up close and lost my grandmother to Alzheimer’s. I immediately thought about the more than 402,000 Canadian seniors living with dementia (including Alzheimer’s) and their families: finally, they have hope.

In a brain with Alzheimer’s, neurons stop working, lose connections with other neurons, and die. Up until now, there were only five medications for Alzheimer’s disease approved by the FDA and four medications approved by Health Canada, all of which target the symptoms of the condition to temporarily slow memory loss and cognitive decline. The causes of Alzheimer’s still have not been identified.

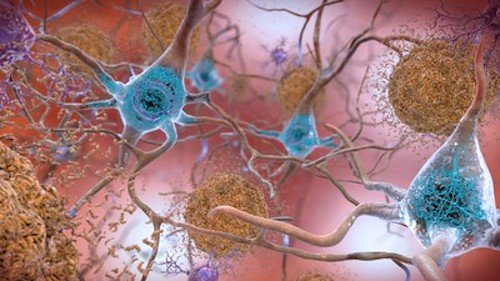

One popular hypothesis for the cause of Alzheimer’s is the amyloid hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that amyloid beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (called tau) are behind the loss of neurons and their connections, and thus the loss of memory and cognitive abilities.

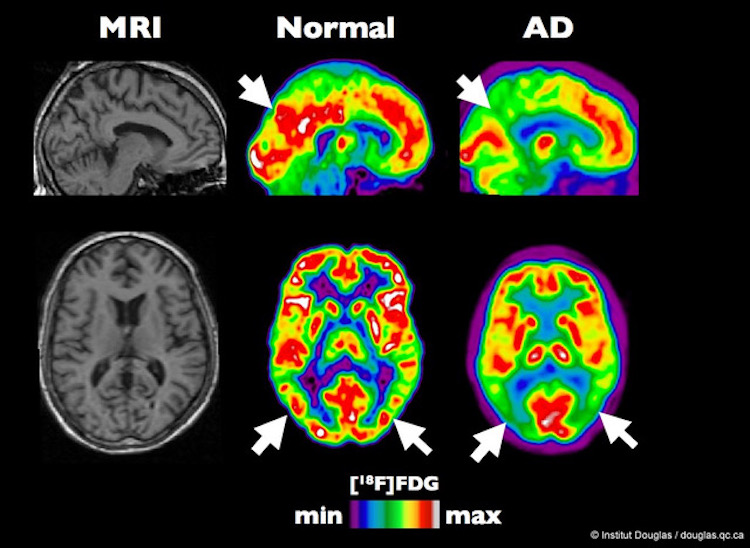

PET scan of a typical brain compared to a brain affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Image by Institut Douglas, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Amyloid beta plaques are formed when the enzyme secretase breaks down the amyloid precursor protein, a large protein found in the fatty membranes surrounding neurons. The proteins produced can be made up of 38, 40 or 42 amino acids. The beta-amyloid, composed of 42 amino acids, is “stickier” than the others and clumps together to form plaques that collect between neurons. Neurofibrillary tangles are the accumulation of the protein tau in nerve cells. Tau that should normally be attached to microtubules inside cells detaches and sticks to other tau proteins forming tangles and disturbing the cells’ function.

The amyloid hypothesis is supported by the significant presence of amyloid beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

Amyloid plaques and tau are biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease. Image by the National Institute on Aging (NIH), CC0 1.0

Aduhelm™, manufactured by Biogen and Eisai, is the first therapy to be approved for Alzheimer’s in 18 years and the first therapy that, according to the manufacturer, addresses the fundamental pathophysiology of the disease: the amyloid beta plaques. The treatment, a human monoclonal antibody given intravenously every month, has been shown to reduce amyloid beta plaques in the brain by 59 to 71 per cent after 18 months of treatment.

Reading more about the drug, I found out that not all of the scientific and medical community shared my excitement, and three FDA advisors had resigned after its approval. The treatment had been under two phase III clinical trials in which Canada participated. Both of these studies were discontinued prematurely by the manufacturer, citing in their statement the “results of a futility analysis conducted by an independent data monitoring committee, which indicated the trials were unlikely to meet their primary endpoint upon completion.”

According to Biogen, this decision was made before receiving all the data. After receiving and reviewing the remaining data, the company came to the new conclusion that the study did meet its clinical endpoint, and submitted it to the FDA on July 8, 2020. None of the 11 advisors composing the independent committee that advised the FDA on the treatment considered the drug to be effective. Nevertheless, the FDA granted approval on the condition that the manufacturer completes another clinical trial to verify the drug’s benefit.

The scientific criticism of aducanumab comes from the fact that, while the clinical trial results show that the drug reduces amyloid beta plaques, there is no scientific evidence that reducing amyloid can offer cognitive benefits for patients. In fact, more than 25 previous trials of other amyloid-reducing drugs have failed to show that they slow cognitive decline. The researchers who criticize the amyloid hypothesis propose that amyloid plaques may be a consequence of the disease rather than its cause. This has led to the suggestion that the amyloid hypothesis could be the reason why we still haven’t developed effective Alzheimer’s treatments, and that reliance on this hypothesis has led to the neglect of other theories, ideas and research opportunities.

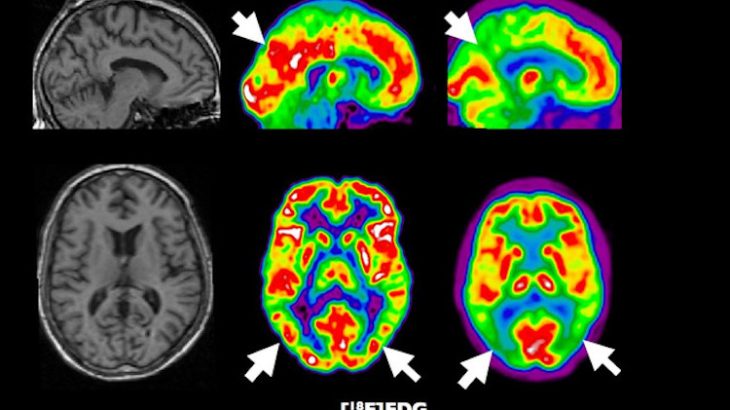

In addition to these scientific concerns, the serious side effects of aducanumab cannot be ignored. The most common include brain swelling, headache, confusion, delirium, disorientation, ataxia, dizziness, vision changes, nausea, and falls. Another major concern is the cost of the treatment: $56,000 USD (approximately $70,000 CAD) per year for patients weighing 74 kgs. Heavier patients would require bigger doses at greater expense. There are also additional costs associated with the treatment, such as the numerous MRIs and specialist visits the patient should undergo for monitoring.

Patients should undergo numerous MRIs to monitor their brains under treatment with aducanumab. Image by Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, CC0 1.0

Patients should undergo numerous MRIs to monitor their brains under treatment with aducanumab. Image by Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, CC0 1.0

Biogen has submitted aducanumab for approval to Health Canada, and the drug is now under review. There is no guarantee that Health Canada will follow the FDA’s lead. Health Canada mentions on its website that “If there is insufficient evidence to support the safety, efficacy or quality claims, HPFB [Health Products and Food Branch] will not grant a marketing authorization for the drug.” Researchers and health professionals from seven Canadian organizations focused on aging and neurodegenerative disease submitted a consensus statement to Health Canada concluding that the approval of aducanumab in Canada cannot be justified based on the information available today. The Alzheimer Society of Canada is collecting the input of people who have been treated with AduhelmTM to talk about their experience via a survey. They will submit the findings to Health Canada to ensure that the experiences of the people being treated are heard, represented, and considered during the review process.

The priority process for drug approval in Canada takes approximately 180 days (compared to 300 days for the regular process). If the drug gets approved, it will be issued a notice of compliance and a drug identification number. Afterwards, it will go through another review by each province to assess whether and how much of the cost would be covered. For now, Canadians who wish to take the treatment must travel to the U.S, and in most circumstances, the treatment would be paid out-of-pocket.

Aduhelm™ isn’t the magical treatment I thought it would be, but it is at least a step forward for research: if the ongoing clinical trial has good results, we know research is headed in the right direction, and if the results are disappointing, researchers will know they need to look elsewhere.

~30~

it was very helpful. Alzheimer is really a scary disease.