Alina C. Fisher, Environmental and Earth Science co-editor

When you think of a wolverine, do you think of an elusive, almost mythical creature with superpowers, or do you think of the comic book character? Most people have heard of the X-Men, either through the movies or the comic book series, but few people know about the real-life inspiration behind the mutant Wolverine.

Wolverines, Gulo gulo, like their mutant counterpart, enjoy their “alone time” and few people are lucky enough to see one in real life. Even wolverine researchers Nicole Heim and Jason Fisher admit they have never seen one off camera. The closest Jason came was tracking a snarling wolverine through the snow – but even though he heard it making terrifying noises at him, he just couldn’t get close enough for a visual ID.

So how do you research an animal that’s so elusive? It is a challenge! Because not only are wolverines elusive, their home ranges can be large – 100–600 km2 depending on their sex and location.

Nicole and Jason are part of the Alberta Wolverine Working Group, a team trying to compare wolverine population density and behaviours in the Rocky Mountain national parks (Banff, Yoho, Kootenay), where human disturbance is minimal, and Kananaskis Country, a mixed-use area where human disturbance is more common. To do this they use a series of camera traps baited with a “juicy beaver carcass.” That carcass makes an irresistible meal, attracting local wolverines (and a slew of other hungry animals like martens, fishers, red and flying squirrels, and even Clark’s nutcrackers, among many others) for a mid-meal photo op.

Nicole Heim (left) and Jason Fisher (right) caught on camera setting up one of their bait stations. Photos: N. Heim & J. Fisher

Each camera trap station allows for a visual ID of individuals with distinct coloration patterns, like Hookneck (below), as well as genetic identification material from hair snagged by barbed wire.

The wolverine known as Hookneck, whose colouration patterns make him easy to identify. His movement over the study site ranged nearly 1,000 km2. Photo: InnoTech Alberta, and Alberta Environment & Parks

Nicole and Jason’s research had some surprising results. They found that the wolverine population size in Banff, Yoho, and Kootenay was around 50 individuals, with a population of only 7 individuals in the adjacent (but less protected) Kananaskis Country.

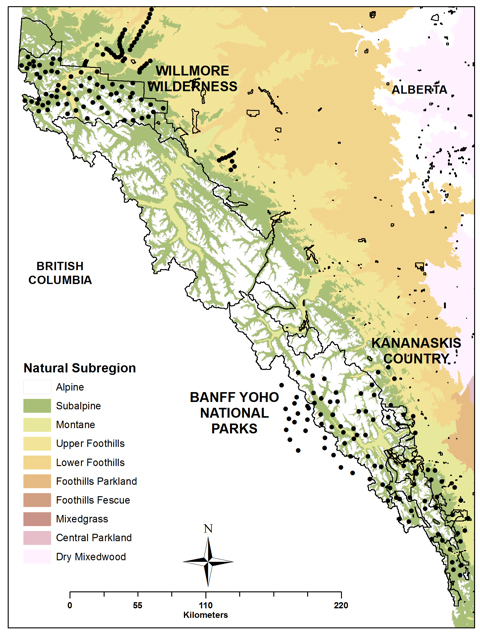

The study area in the Canadian Rocky Mountains stretches from the Willmore Wilderness in the north, to Banff and Yoho National Parks in the south. Dots indicate bait stations, each consisting of a camera trap and hair snag. Photo: InnoTech Alberta.

The prevailing thinking in the US wolverine research community is that populations are decreasing (and ranges shrinking) because of climate change. However, the Alberta Wolverine Working Group is showing that climate change is only half the problem. Landscape change due to human use is the other big culprit, and the animals are avoiding habitats that have been disturbed by resource extraction. But it’s not just human activity pushing the wolverines out – other medium-sized carnivores that do well in human-impacted landscapes may be increasing, leading to increased competition with wolverines.

It can be hard to eke out an existence as a wolverine. They have a fearsome reputation, and videos abound on YouTube of wolverines fighting off wolves or bears. However, a wolverine’s bark may be more than its bite. Even though wolverines may show their teeth and snarl, an individual wolverine’s response to a competitor depends on age, sex, and aggressive attitude – after all, it is a medium-sized carnivore that could be killed by a grizzly bear or wolf. According to Nicole, it’s a trade-off between risk and reward; trying to find kill sites to scavenge, but where other bigger and meaner carnivores may be present.

The interactions or processes making these disturbed areas in Kananaskis Country unsuitable for wolverines have yet to be definitively established. However, as Nicole notes, “The significant reduction in population numbers outside protected areas suggests that wolverines are indeed vulnerable to our ever-increasing land use demands.”

Current management decisions in Alberta are based on the assumption that the “working landscape” – where wildlife and human activities overlap – supports biodiversity. But Jason points out that their research challenges this assumption for wolverines, and that managers need to “adjust decision-making accordingly.” The long-term survival of wolverine populations in the central Rocky Mountains, and elsewhere, will rely heavily on minimizing disturbance near the boundaries of our protected areas.

Wolverines’ shyness also works against them. Grizzly bears are often spotted in the wild, and if we stopped seeing them, there would be a public outcry and resource managers would act quickly to save the population. The sad fact is that as long as we think of Hugh Jackman rather than Gulo gulo, the conservation needs of wolverines will be overlooked.

So how do you gain the necessary public attention to support wolverine conservation efforts? You recruit Hugh Jackman to do public service announcements!! Just kidding… It is a tough question, and one that researchers and wildlife managers alike struggle with. What do you think? What would you do? Wolverines need your help!

–30–

Feature image: The elusive wolverine. This individual was caught on camera making off from the bait station with a large piece of beaver carcass. Photo: InnoTech Alberta, and Alberta Environment & Parks

Wolverine researchers in the US don’t believe that climate change is the only culprit in wolverine range reductions. We believe that climate change makes other issues exponentially worse for the species. And the effects of both climate change and human development will depend strongly on where in the wolverine’s range one is looking at the population.

The initial range reductions observed in the lower 48 states of the US were probably the result of predator extermination campaigns in the early 20th century. Canada probably saw some of this as well, as reports exist of 100+ wolverines killed over several years as a by-product of wolf and coyote killing campaigns in places like, for example, the Yukon. Currently we don’t have any evidence that wolverine populations in the US are retracting further; in fact, they appear to be recolonizing vacant habitat. But our overall data are not good enough to understand whether there are current ongoing range reductions or population declines across the entire meta-population of the lower 48. So we are not claiming that any observed decline or reduction is the result of climate change. We are claiming that climate change will be the major driver of future declines and reductions, as it will amplify the effects of human development, trapping, etc.

– Rebecca Watters, Executive Director, the Wolverine Foundation.

Thank you for your response. I have forwarded your comments to the researchers whose work is profiled in this piece.

-Alina Fisher

Hi Rebecca, the statement in the blog “The prevailing thinking in the US wolverine research community is that populations are decreasing (and ranges shrinking) because of climate change”, which draws from our discussion in the scientific article, stems from an honest and empirical appraisal of the published literature rather than an inference about researchers’ beliefs.

The pivotal Copeland et al. (2010) paper (http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/z09-136#.WeeAU9KnHmE) claims that spring snow is a wolverine niche requirement, and that snow is needed for wolverines to successfully den and rear young. This was followed up by the refrigeration-zone hypothesis which states wolverines need snow to cache ephemeral food (http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1644/11-MAMM-A-319.1). Brodie and Post (2010) extended this argument to suggest wolverines’ historical declines were due to declining snowpack (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10144-009-0189-6), although their analysis was contested by Copeland et al. (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10144-010-0242-5).

Finally, it is important to note that McKelvey, Copeland et al. 2011 (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1890/10-2206.1/full) discuss “historical and future” climate change multiple times. The authors state explicitly “IF … the extent of persistent spring snow cover has constrained *current and historical* distributions, then it is reasonable to assume that it will also constrain the wolverine’s future distribution.”

Thus, there is indeed a prevailing view that snow has constrained both historical and current distributions, not just future distributions, as you suggest. In comparison, there is very little research on the impacts of US land-use change on wolverines’ distributions, with a few exceptions (https://trid.trb.org/view.aspx?id=786596; https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/84/1/92/2373719/Evaluation-of-Landscape-Models-for-Wolverines-in).

The strong focus on climate change in the US, notably excluding landscape change, is summed up in the legal brief from Defenders of Wildlife vs. Sally Jewell (http://conbio.org/images/content_policy/16-04-04_Doc._108_ORDERb.pdf). The latter states “Based upon Copeland (2010) and McKelvey (2011 ), the latter of which the Service referred to as both the most sophisticated and “best available science for projecting the future impacts of climate change on wolverine habitat” (PR-00744), the Service came to the following conclusions in the Proposed Rule: *The primary threat to the [wolverine] is from habitat and range loss **due to climate warming** . . . . Wolverines require habitats with near-arctic conditions wherever they occur… Other threats are **minor in comparison** to the driving primary threat of climate change; however, cumulatively, they could become significant when working in concert with climate change if they further suppress an already stressed population. These secondary threats include harvest (including incidental harvest) … and demographic stochasticity and loss of genetic diversity due to small effective population sizes …* â€.

No mention is made of landscape change; very few studies explicitly examine ongoing or future effects of landscape change, and this stressor is not on the radar for the listing of wolverines. Ours is one the first studies that explicitly weighs evidence for landscape change against evidence for climate change hypotheses. So, while the statement in the paper and the blog was indeed a necessary generalization, it does reflect an honest assessment of the weight of existing scientific literature, and the views expressed in the proposed listing for wolverines.