Chantal Mustoe, Chemistry co-editor

In October 2013, in the case of Regina v. Bornyk, a man was arrested, tried and acquitted of breaking and entering in Surrey, British Columbia. The judge assessed the fingerprint evidence himself and dismissed it due to “unexplained discrepancies” and possible effects of “institutional bias” in fingerprinting and the “subjective certainty” of the expert witness. According to Della Wilkinson, a fingerprint specialist in the RCMP and recipient of the Edward Foster Award for her advancements in fingerprinting, this is the first time the validity of the role of fingerprinting in forensics had been called into question in a Canadian court of law.

The Canadian legal system is certainly not the first institution to doubt fingerprint evidence. In 2001, Simon Cole, professor of criminology at Cornell University, described fingerprinting as “so last century”. He questioned its “reliance on human observation” and our cultural faith in fingerprinting, citing two misidentified fingerprints resulting in incarcerations for murder. In response to the concerns of Cole and many others, impartial organisations have conducted external reviews of this technique. Other specialists like Wilkinson continue to make breakthroughs in the science of fingerprinting and claim we can still glean much from the oily marks we leave behind.

Is fingerprinting an archaic relic of the late 1800s or does it still have a place in the criminal justice system? Before we try to answer that, let’s delve into the science of fingerprints. What are fingerprints made of? How do we make fingerprints more visible? And what can fingerprint analysis tell us?

The fingerprints themselves are made of water, salt, and amino acids excreted by our sweat glands, and oils and fatty acids from the sebaceous glands on our foreheads. Come again? Yes, from our foreheads. These oils and fatty acids build up on our fingers through our natural tendency to touch our face and hair.

There are a few different types of fingerprints: exemplar, or known prints deliberately acquired from someone with their consent, patent or plasticprints, which are easily visible to the naked eye, and latentprints, the accidental impressions left on a surface by the ridged skin on our fingertips. For this article, I’ll focus on latent prints because they are the most interesting from a chemistry perspective.

Because of the variety of chemicals in our fingerprints, we have a multitude of methods to enhance them. We can discount water. While water comprises almost 90 per cent of a fresh fingerprint, most of it evaporates after 24 hours. The simplest component to detect is the oils from the glands on our foreheads. Fine powders such as sticky side powder or even cocoa powder will stick to these oils and make the prints visible. While dusting for fingerprints is affordable and straightforward, this physical interaction can cause unintended damage to the prints.

Non-destructive techniques for developing fingerprints include iodine fuming, exposure to silver nitrate, ninhydrin, and cyanoacrylate (superglue). Each of these techniques relies on a different chemical component of the fingerprint:

- Iodine dissolves easily in oils, and the sublimation of iodine in a gas chamber with the fingerprint results in the fingerprint turning brown.

- Treatment of a fingerprint with a silver nitrate solution results in black silver chloride depositing on the fingerprint ridges as the solution interacts with the chloride salts in the sweat.

- Ninhydrinreacts with the trace amounts of amino acids turning the fingerprints purple!

- Exposure to gaseous cyanoacrylate (heated superglue) results in polymerisation (hardening of the glue) onto the fingerprint ridges.

The variety of techniques is essential because no one technique suits the quality of every fingerprint or surface.

Wilkinson has even developed a technique to visualise latent fingerprints on a corpse. Developing fingerprints on skin is particularly difficult as skin has many, if not all, of the same molecules present in the latent fingerprint. Using substances to highlight the oils, salts and amino acids in a fingerprint is much less effective when the background contains the same chemicals. Wilkinson’s way to tackle this problem builds on the cyanoacrylate method of depositing a polymer on the fingerprint ridges. Once the polymer has coated the fingerprint, a chemical can be introduced into the polymer so that when the skin is viewed under a certain type of light the fingerprint, and only the fingerprint, will glow.

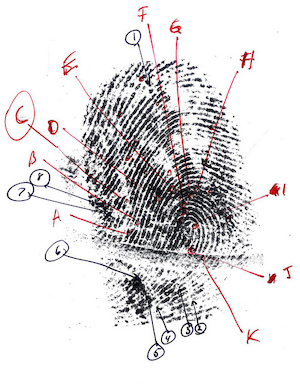

We have a plethora of ways to develop fingerprints, but how can we be sure that a fingerprint belongs to a specific individual? Our assumption that everyone has a unique fingerprint goes back to 1892 when Francis Galton showed that the probability of two individuals having identical fingerprints is less than 1 in 64 billion. Even identical twins have different fingerprints despite their identical DNA. While it is not possible to prove that every individual has a unique fingerprint, we can look at the experts’ ability to identify fingerprints.

In response to outcries from the academic community, the President’s Counsel of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) undertook an external review of the fingerprinting process. Della Wilkinson commended the study in her interview with the fingerprint-focused Double Loop Podcast. Wilkinson said this much-needed validation found that false positives, or mistaken identifications, occurred less than 0.2 per cent of the time when experts assessed fingerprints while a lay person’s analysis of the fingerprints resulted in over 55 per cent false positives.

These statistics brought into question the judge’s decision to dismiss the fingerprint evidence in Regina v. Bornyk. In January 2015, the Crown appealedBornyk’s acquittal on the grounds that the judge had acted as “advocate, witness, and judge” with respect to the fingerprint evidence. The false positive rates from the PCAST study were presented to discredit the judge’s claims of “institutional bias” and the expert’s “subjective certainty”. Multiple experts, including Della Wilkinson, addressed the “unexplained discrepancies” and verified that the crime scene fingerprints matched Bornyk’s known prints. The appeals judge declared the fingerprint evidence admissible, and the verdict was overturned.

While many other tools are being added to the arsenal of forensic science, scientific advancements and the external validation of fingerprinting mean that this centuries-old tool will be with us for years to come.

~30~F

One thought on “To fingerprint or not to fingerprint? That is the question”

Comments are closed.