By Michael Ralph Limmena, Health, Medicine & Veterinary Science co-editor

Canadians are living longer than ever — 2015 marked the first year that the number of Canadians older than 65 surpassed the number of children younger than 15.

Unfortunately, the Alzheimer Society of Canada’s latest projections paint a grim picture for the future for many of the country’s elderly. Its newest study predicts that by 2030 more than a million Canadians will be living with dementia. This number will increase to about 1.7 million by 2050.

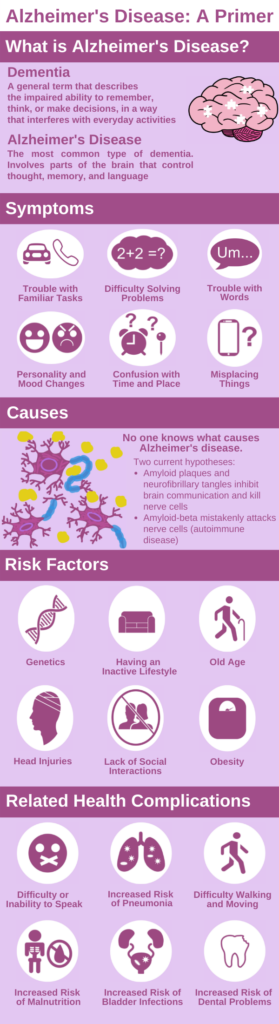

The cause of Alzheimer’s disease is unknown but researchers have a good understanding of the biological processes involved in the disease. Multiple risk factors have been identified that may lead to Alzheimer’s if left untreated. Infographic by Michael Ralph Limmena.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, accounting for approximately 60-70% of all cases. Our understanding of Alzheimer’s has significantly improved since Dr. Alois Alzheimer first documented it in 1906. But scientists and researchers haven’t found a cure for Alzheimer’s and still do not know what causes it, although they have proposed many hypotheses.

What is and isn’t Alzheimer’s disease?

As we get older, our bodies naturally change. We may find our hair graying and experience more joint pain. Our brain changes too, and the memory problems that many of us will experience are normal. Usually, this age-related memory loss causes only minor problems. We may forget where our keys are or take longer to learn new information, but we often remember what we forgot later in the day.

Age-related memory loss affects approximately 45% of people over 65 years old. Although Alzheimer’s also involves memory loss, the disease is not a normal part of aging and has far more serious consequences.

Alzheimer’s disease is a degenerative brain disorder in which a person’s memory, language, and reasoning capabilities deteriorate significantly over time. The brain consists of an extensive network of neurons or nerve cells. Neurons located all around the body send chemical signals to each other. This communication between neurons allows our bodies to move and feel, and our brains to think and remember. However, in the case of Alzheimer’s, the communication between neurons becomes interrupted. Over time, many neurons die.

Often, Alzheimer’s begins with mild memory loss, which can easily be mistaken for normal aging. Over time, this condition progresses and causes serious problems. Some typical signs of Alzheimer’s include memory loss, difficulty completing familiar tasks, and trouble with words. Sufferers may become unable to communicate, move, or recognize their family and friends. They may also develop problems eating and drinking. Because people with Alzheimer’s may have difficulties swallowing, food and drink are sometimes accidentally inhaled. This food inhalation allows the bacteria from the mouth to enter the lungs, where it can eventually cause respiratory infections.

Risk factors for Alzheimer’s

Although scientists do not know what causes Alzheimer’s, they have identified several key risk factors that increase the probability that a person will develop the disease. Age is the biggest risk—the likelihood of developing the condition doubles every five years after 65 years old. Having a family history of Alzheimer’s is another significant risk factor. The Alzheimer’s Association offers a detailed explanation of the genetic risk of developing the condition.

While we cannot change our age or genetics, research has identified several preventable lifestyle factors that increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. These include obesity, diabetes, poor diet, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption.

Conflicting hypotheses

Although Alzheimer’s was first documented over a century ago, scientists and researchers still do not know what causes the disease. Two current theories are the amyloid hypothesis and the autoimmune hypothesis.

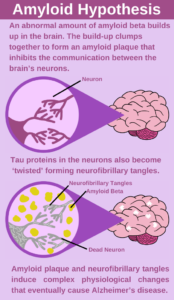

The amyloid hypothesis

For the past 30 years, the most prominent hypothesis was that Alzheimer’s disease results from an abnormal build-up of amyloid beta and amyloid plaques have been the focus of research; however, this hypothesis has recently fallen out of favour. Infographic by Michael Ralph Limmena.

The autopsied brains of Alzheimer’s patients have two distinct abnormal features: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. When proteins called amyloid beta (amyloid-β) clump together, they form dense masses known as amyloid plaques. These plaques usually occur in the spaces between neurons. Some researchers suggest that these plaques may cause a complex immune reaction that eventually causes neurons to die. Neurofibrillary tangles are ‘twisted threads’ of a protein called tau. The tau protein helps distribute nutrients throughout a neuron. In Alzheimer’s disease, the tau proteins become ‘twisted’ and clump together. Together with amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles are hypothesized to damage neurons and eventually cause impaired memory and judgment.

The amyloid hypothesis gained significant support after studies identified several gene mutations that increase amyloid plaque formation among people with a family history of Alzheimer’s. Animal studies further supported this hypothesis when genetically modified mice with mutations that increased amyloid plaque production eventually developed Alzheimer’s-like symptoms.

Recently, the amyloid plaque hypothesis has fallen of favour. If amyloid-β is the primary cause of Alzheimer’s disease, drugs that prevent amyloid-β production and aggregation should prevent declines in cognitive abilities. But no therapies have successfully prevented cognitive decline despite targeting amyloid-β. Studies also document several cases of seniors with amyloid plaques that show no cognitive impairment, and there are inconsistent relationships between declines in cognition and the severity of amyloid plaques. These inconclusive results have prompted scientists to develop other hypotheses that may explain the causes of Alzheimer’s disease.

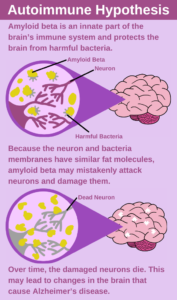

The autoimmune hypothesis

Recent research supports the hypothesis that Alzheimer’s disease is an autoimmune disease, caused by amyloid-β mistakenly attacking neurons instead of harmful bacteria. Infographic by Michael Ralph Limmena.

One alternative hypothesis suggests that Alzheimer’s disease is not a brain disorder but an autoimmune disease—in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the body instead of protecting it. This hypothesis proposes that amyloid-β is a natural part of the brain’s immune system that protects neurons from bacteria. In his September 2022 Conversation article, Dr. Donald Weaver based at the Krembil Brain Institute in Toronto, explains that “because of striking similarities between the fat molecules that make up both the membranes of bacteria and the membranes of brain cells, beta-amyloid cannot tell the difference between invading bacteria and host brain cells, and mistakenly attacks the very brain cells it is supposed to be protecting.” Dr. Weaver suggests that instead of targeting amyloid-β itself, researchers should target other molecules involved in the brain’s immune response. This course of action may lead to new and effective Alzheimer’s treatments.

Although there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, our understanding of the disease has improved immensely in the past decade. The hypothesis that amyloid alone causes Alzheimer’s is no longer supported, but researchers still believe that amyloid-β is one of many contributing factors to Alzheimer’s disease. As Alzheimer’s research continues and new theories and hypotheses are developed and tested, many researchers envision a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. This is good news for the ever-increasing number of elderly Canadians.

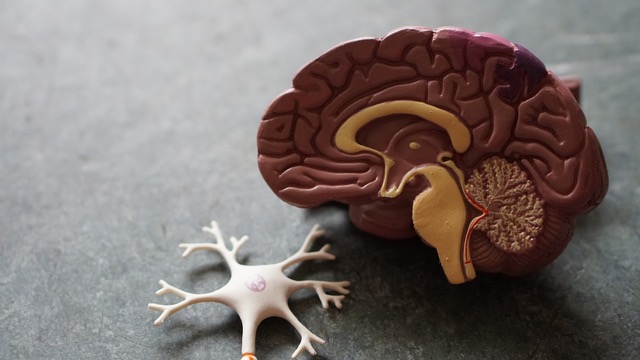

Feature image: These models show the anatomy of the brain (in cross-section) and a neuron (not-to-scale). Photo: Robina Weermeijer, Unsplash License.