Christian Phillips, New Science Communicator

One hundred kilometres north of Whistler, BC, up the Lillooet River, lies Mount Meager, a sleeping giant. Mount Meager is just one of 13 volcanoes that punctuates the west coast, from California to Alaska.

Alex Wilson and Glyn William-Jones measure the composition of the gas being emitted by a fumarole at Mount Meager. Photo by Gioachino Roberti (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu) CC BY NC ND

However, it is starting to look like this sleeping giant may not be asleep much longer. Three large holes on the mountain’s Job Glacier have started emitting toxic gas and steam. Even before these developments, the mountain was attracting geologists’ attention as much of its ice cover has melted during the last 30 years.

Mount Meager last erupted 2,400 years ago.

Researchers at Simon Fraser University, including Glynn Williams Jones of the SFU Physical Volcanology Group, are studying it, seeking to identify the potential for and dangers of another eruption.

“The issue with Mount Meager, in terms of its activity, is that right now we don’t have a good feeling for exactly what its behaviour is.” Williams Jones says. “If it were to erupt, and that’s a big “if,” we can’t say when or even what scale the eruption would be.”

Welcome to the Ring of Fire

If you live in British Columbia – or anywhere near the west coast of North America – you live in the Ring of Fire. This zone, which outlines the entire Pacific region, is home to almost 90 per cent of the world’s earthquakes and 75 per cent of its volcanoes.

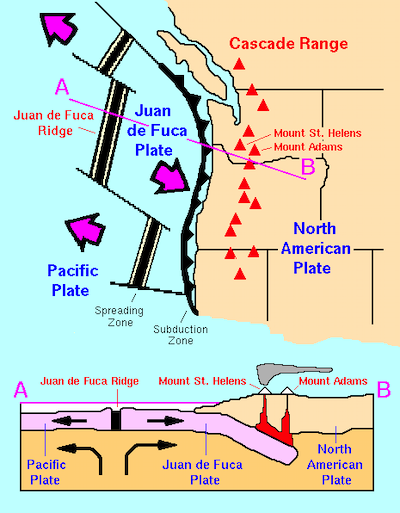

The Juan de Fuca oceanic plate is subducting beneath the North American continental plate, giving rise to earthquake activity and volcanoes throughout the Cascadia region. Red triangles represent the Cascade Range volcanoes. Image by USGS

The geologic activity is due to plate tectonics. The Earth’s surface is made up of continental and oceanic plates. Think of these plates as big slabs of rock that make up each continent (continental plates) and lie beneath every ocean (oceanic plates). These plates interact with each other by sliding beneath, above, or alongside neighbouring plates.

Oceanic plates absorb tremendous amounts of water, so when an oceanic plate slides under the edge of a continental plate, the weight of the overlying continental plate forces the oceanic plate deep into the Earth. There, high pressures and temperatures force water out of the subducting oceanic plate. This free water travels upwards to the overlying continental crust, where it becomes absorbed through a process called hydration. When rock becomes hydrated, its melting temperature is lowered. This generates magma – lava found beneath the Earth’s surface.

A volcano forms when this magma from within the Earth’s upper mantle works its way to the surface. The pressure from magma and its lesser density pushes it up through the crust. As magma reaches the surface, it cools and hardens into rock. Over millions of years, it forms the large volcanic mountains that we see today.

Here on British Columbia’s coast, we sit above an active tectonic boundary. Thirty kilometres beneath our feet, the Juan de Fuca oceanic plate is grinding its way under the western edge of North American continental plate.

Sleeping giants

Vancouver has Mount Baker, Seattle has Mount Rainier, Portland has Mount Hood, Crescent City has Mount Shasta. North America’s west coast is lined with 13 volcanoes that form the Cascade Range.

Most of these volcanoes are quiet, but for how long?

In 1980, the top half of Mount St. Helens blew off in a cataclysmic explosion of mud, gases and ash, causing the largest landslide in US history. Ash from the eruption travelled 2,000 kilometres. Fifty-seven people died, and damage totalled $1.1 billion USD.

If another Cascade Range volcano were to erupt, it could have similarly devastating consequences.

Monitoring the volcanoes

Eruptions like the one at Mount St. Helens are costly in terms of money and lives. Although they cannot be prevented, the risk can be minimized.

Scientists have been watching many of the Cascade volcanoes, seeking to be better prepared in the event of another eruption. Before an eruption, earthquake-like shocks can provide warning. In the months before Mount St. Helens erupted, over 2,400 shocks shook the region. With adequate sensors and emergency procedures in place, researchers could detect these earthquakes and reduce overall risk.

Currently, no volcano in Canada is monitored.

Simon Fraser University’s Glynn Williams Jones believes that more needs to be done to monitor volcanoes such as BC’s Mount Meager, and that the installation of sensors to detect these pre-eruption shocks, would be in our best interest.

“If you’re not monitoring, then you don’t know when it’s going to go, and even some of the best studied volcanoes can catch you by surprise.” Williams Jones says. “If we don’t have anything, then we have absolutely no chance of knowing. That’s why [monitoring volcanoes] is important.”

Starting in 2019, Williams Jones and the Centre for Natural Hazard Research are beginning work on a centralized system where scientists and the public can get information on natural hazards in their area. The “one stop shop,” as Williams Jones call it, will draw information from the centre’s database and external sources. It will provide information about not only what occurred in the past, but what people can do if a natural disaster were to occur.

Mount Meager hazards

Mount Meager looms over the north end of Pemberton Meadows, about 100 kilometres from Whistler, BC. The sleeping volcano has been showing signs of stirring in recent years. Photo by Dave Steers CC BY 2.0

Mount Meager’s smoking vents and increased ice melt are cause for concern. As the ice melts and gas escapes through these holes, the cap holding back the magma beneath the volcano loosens. We can compare this to opening a shaken bottle of soda. When you remove the cap – or glacier – the pressure inside the bottle – or volcano – can push the contents out suddenly and explosively.

However, landslides may be the bigger danger. One of Canada’s largest landslides took place on the mountain in 2010. If Mount Meager erupted, the resulting landslide could be even bigger.

In addition, an eruption would instantly melt the mountain’s remaining ice. The resulting mud and water would rush downhill into the Lillooet River, flooding the valley and putting the entire area at risk.

~

Living on North America’s west coast means spectacular scenery, access to the ocean, mountains, forests and beaches, as well as to urban, rural and wilderness environments. Though it also comes with geological hazards, many of which cannot be prevented.

Although the region’s volcano hazards are great, the risk of these volcanoes erupting anytime soon remains small. Most of the region’s volcanoes have been quiet for thousands – even millions – of years.

However, this doesn’t mean we should be complacent. By monitoring the seismic and volcanic activity of Mount Meager and other Cascade volcanoes, we can increase our ability to prepare for eruptions, save lives, and decrease the potential for damage.

~30~

Simon Fraser University student Christian Phillips wrote this post as part of Science Borealis’s Spring 2019 Pitch & Polish, a mentorship program that pairs students with one of Science Borealis’s experienced editors to produce a polished piece of science writing.

Read more about Pitch and Polish>

Mount Lassen, in Northern California, erupted in 1917. That makes it the most recent North American volcano to erupt prior to MSH.

so amazing. i’m scared of this mountain

Mount Meager is not the second most recent North American volcano to erupt. Far from it actually. Several North American volcanoes have erupted in the last 2,400 years, including Tseax Cone, The Volcano, Kostal Cone and Mount Edziza in Canada, Mount St. Helens, Lassen Peak, Mount Shasta, Mount Baker, Mount Rainier, Mount Hood and Glacier Peak in contiguous US, as well as many others in Alaska and Mexico.

Don’t neglect the Alaskan volcanos

Did someone say it was?

Mount Rainier about 7 years around the time Wisconsin was having al those booming cracking sounds( ….Fissures?!)people watched “MT Rainer” blow black smoke(cinders) on the right side of its upper top flank, just below the top like it puffed for a moment and you could see the hole with cinders on internet satellite( Not map picture!) along the outer edge of the smoking opening and the university people say it is two three inches wider along bottom then a few year ago not taller! also now the circle hole formation on top is almost double maybe filling on that side? facing eastward from the park service parking area!! seems ok now just made people think more about your own family and their safety!! Just something to note!