Catherine Lau, Biology & Life Sciences co-editor

It’s happening again. You are reliving that moment in your head and you can’t stop it. No, it’s not a bad dream, it’s a real memory and it stunts you and makes you unreasonably nervous. Living a normal life suddenly becomes a challenge. What can you do? Turn to an unlikely source of help: Art.

Reliving a traumatic memory that increases anxiety is a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It impacts 7 or 8 out of every 100 people at some point in their lives. PTSD is often treated with prescriptions for antidepressants and cognitive behavioural therapy , although neither the drugs nor the therapy is always effective. Clearly, there is a need to improve PTSD treatment.

So, how can art possibly help someone after trauma? Art therapy is based on a blend of psychotherapy and art-making that gives patients another way to express themselves. The focus is not the final product but the process of creating art, which can help a person communicate, resolve traumatic memories, reduce stress and reflect on the meaning of her artwork. This can provide the insight necessary to help her psychological recovery.

A piece I created during an art therapy workshop at an independent art school (Metafora) in Barcelona to represent how I felt during my solo backpacking journey through Europe. Artwork + photo: Cat Lau

Drawing, painting or sculpting are commonly used in art therapy sessions to help patients communicate non-verbally. This is especially relevant for PTSD sufferers because the trauma is seen as a non-verbal problem. When someone faces an overwhelming threat, their higher cognitive functions, such as speaking, are halted and their fight or flight stress response is triggered. Their thoughts are still stored, but they take the form of non-verbal fragments with no specific timeline. So, when the trauma is over and verbal thinking kicks back in, these disjointed memories can intrude into the consciousness through triggers, which are related to the trauma. For instance, if a soldier has a near-death experience involving an explosion, the sight of a campfire in his backyard might set off a traumatic memory.

Currently, art therapy is trying to gain credibility through scientific evidence. Thanks to the advent of brain scanning technology, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEGs) we can look at brain activation and electrical activity to learn more about how PTSD manifests in the brain and how art therapy can help.

Evidence from fMRI studies pinpoints the anterior cingulate cortex as the area of the brain involved in controlling our emotions. This brain region is relatively inactive in PTSD patients who are triggered by script-driven imagery – an audio script that clinical psychology researchers use to evoke a traumatic experience. This lines up with clinical observations of patients who have difficulty handling negative emotions brought on by cues associated with their trauma. On the other hand, non-verbal information activates the right orbitofrontal cortex, an area of the brain that also houses traumatic memories. So, researchers hope to use the non-verbal expression of art therapy as a way to help PTSD patients control their negative emotions when their traumatic memories are triggered.

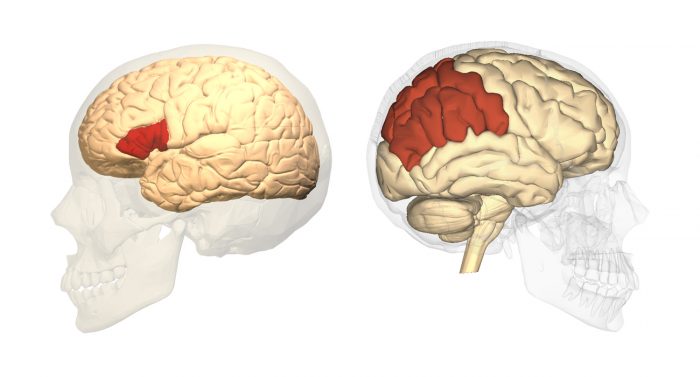

Alpha brain wave activity was reduced in a part of the left hemisphere called the Broca’s area (left image) which is related to verbal production of speech, while brain wave activity was much better in the right hemisphere of the parietal region (right image), which is believed to be involved in visual art creation. Left: Database Center for Life Science, Wikimedia Commons; Right: Anatomography, Wikimedia Commons

EEGs are also being used to shed light on the benefits of art therapy. When neurons fire, they are recorded by the EEG and sorted into waveform bands, which include delta, theta, alpha and beta. Alpha rhythms, in particular, have been shown to play a role in art making as well as exercise and meditation. While alpha waves are associated with a relaxed state of mind, which is certainly important to combat increased anxiety in PTSD, they also reveal another reason to implement non-verbal therapies. In a recent case study of a military veteran with PTSD, alpha wave activity was reduced in the part the brain responsible for verbal production whereas the brain wave activity seen in the area of the brain involved in visual art creation was much higher. After two years of art therapy sessions, he showed improved health and was optimistic about achieving full recovery. In situations where verbal communications may be compromised, non-verbal therapies such as art therapy can be more effective than talking.

Visual art can help us communicate and express our thoughts in a non-verbal way. Photo: Save the Children, BY CC

While evidence increasingly supports art therapy, we are already seeing Canadian programs open up to this unconventional treatment. As of 2015, the Department of Veterans Affairs Canada has expanded mental health services to include psychotherapies such as art therapy for veterans. There are also programs available to young refugees who have come to Canada to escape their war-torn countries, as well as those who have experienced sexual assault or domestic violence.

It will be interesting to see what the future has in store for art therapy as we learn more about our brain. Perhaps by taking a holistic approach, involving both art and science, we can provide better treatment options for the people who need them most.

–30–

Banner image by Stefan Schweihofer, Pixabay