The detectives

The Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative is a national network of wildlife researchers, educators and policy advisors who are on the lookout for threats to wildlife. At the British Columbia node in Abbotsford, B.C., McGregor works as a veterinary pathologist, investigating animal deaths. Since completing her master’s degree on white nose syndrome, a deadly bat disease that has devastated bat populations across North America, she’s developed a special eye for the only mammals capable of flight: bats.

The investigation

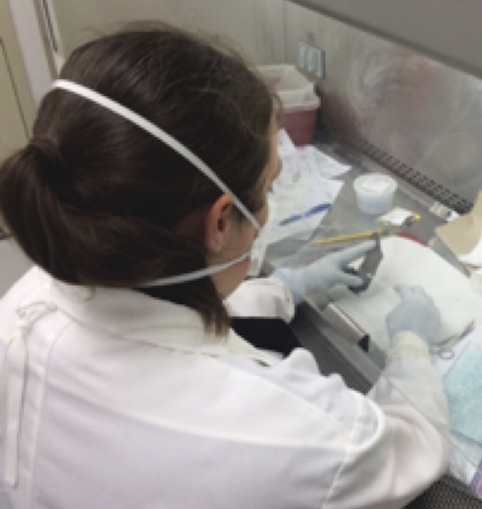

Dr. Glenna McGregor swabs a bat’s wing during a necropsy. Photo by Glenna McGregor, used with permission

Investigating bat deaths is no easy task. Since 2015, McGregor has necropsied hundreds of bats, some of them weighing as little as one gram.

“They’re very small,” says McGregor, “and they tend to rot really quickly, so desiccated – we call them crouton – bats aren’t uncommon. But it’s neat. Their wings are really neat, and then when you look inside, their organs are arranged just like they would be in a primate, really, just in miniature form.”

Bats are swabbed for diseases like rabies, and their tiny carcasses are carefully examined for evidence of what caused their death. Some bats have external puncture wounds; others are diagnosed by examining their tissues under the microscope.

The culprits

The most dangerous culprits McGregor has identified so far are domestic cats.

“There are some cats that are real bat serial killers, so you’ll get 10 bats from one location that have all been killed the same way, likely by the same cat,” she says.

However, because cats will often bring killed bats to their owners who then submit them to the bat mortality study, McGregor emphasizes that their sample likely overrepresents cat predation.

Free-roaming cats are the biggest threat to bats in B.C. Photo by Jordan Gatto-Bradshaw, used with permission

Other bats die of emaciation, which is harder to diagnose in a necropsy. Bats hibernate over winter, and even healthy bats will be on the brink of emaciation come springtime. Bats also don’t show the same types of changes to their fat stores that other mammals do when they’re emaciated. In other mammals that are nutrient-deprived, the fat stored in their bone marrow turns to a melted butter–like yellow jelly as the body uses the fat up for energy. Bats don’t store fat in their bones, so they don’t show this telltale sign.

Still, McGregor has found that many bats are emaciated, and she doesn’t know why. “It could be a reflection of decreased insect abundance,” she suggests. “It could be a reflection of pesticide exposure. We’re not sure why there are such high rates.”

Bats in B.C. eat insects, and if insect populations are reduced by pesticides, bats can struggle to find food to eat. Bats also consume the pesticides themselves through contaminated food and water. These compounds can then accumulate in their tissues and compromise their health.

One suspect that seems to be proven innocent for now is infectious disease.

“We see very little, remarkably little infectious disease as a cause of death, compared to other domestic animals that I look at. Or even compared to other wildlife species, it really seems quite infrequent,” says McGregor. Bats are known for coexisting with diseases that cause severe illness or death in other animals, with white nose syndrome being a notable exception.

Justice for bats?

White nose syndrome was detected in Washington state in 2016. As it approaches B.C., interest in maintaining the province’s bat populations has increased. Image by PublicDomainImages, Pixabay, CC0

Despite the threats bats face, there is reason to be hopeful about the future of bats in the province.

“B.C. has a bigger network of bat enthusiasts than I’ve ever seen before,” McGregor says. “It is phenomenal. There’s a really great group of really dedicated, predominantly biologists and conservationists and volunteers who are just really keen on bats. Like, at first it was kind of hard getting carcasses because everyone wanted them. I’ve never had to compete for a bat carcass anywhere else.”

Community Bat Programs of B.C. plays a large role in educating the public on how to coexist with bats, including providing guidelines on how to safely exclude bats from a building. The organization also coordinates reporting of bat carcasses and bat roosts. By reporting bats, members of the public can help researchers keep tabs on bat populations.

As white nose syndrome looms ever closer – it was detected in Washington state in 2016 – the interest in maintaining our bat populations has increased. Three North American bat species have already suffered losses of 90 per cent of their population. Two of these species are found in B.C., and our populations are still safe from white nose syndrome… for now.

One way that people can help is by keeping their cats indoors or supervising their outdoor access.

McGregor explains the losses that can occur with even one killed bat.

“Bats live for upwards of 40 years and tend to have one pup a year, so saving one individual has quite an impact on a population,” she says. “Everyone thinks of them as mice of the sky, but they’re more like elephants really for reproductive strategy.”

~

Banner image: Half of the 16 bat species in British Columbia are either vulnerable or threatened. Bat photo by Cory Olson, used with permission

Western College of Veterinary Medicine student Imara Beattie wrote this article as part of Science Borealis’s Summer 2021 Pitch & Polish, a mentorship program that pairs students with one of our experienced editors to produce a polished piece of science writing.

Read more about Pitch and Polish>

it was great. I love the text about strange secrets.