By Katie Compton, Policy & Politics editor

Research has confirmed something that parents and teens have known for a long time: teenagers stay up later and sleep in longer than other age groups. This sleeping pattern isn’t an act of rebellion or a sign of laziness – it’s rooted in teens’ natural circadian rhythm. Forcing teens to operate on the sleep schedules of adults may have negative consequences for their health.

What is a circadian rhythm?

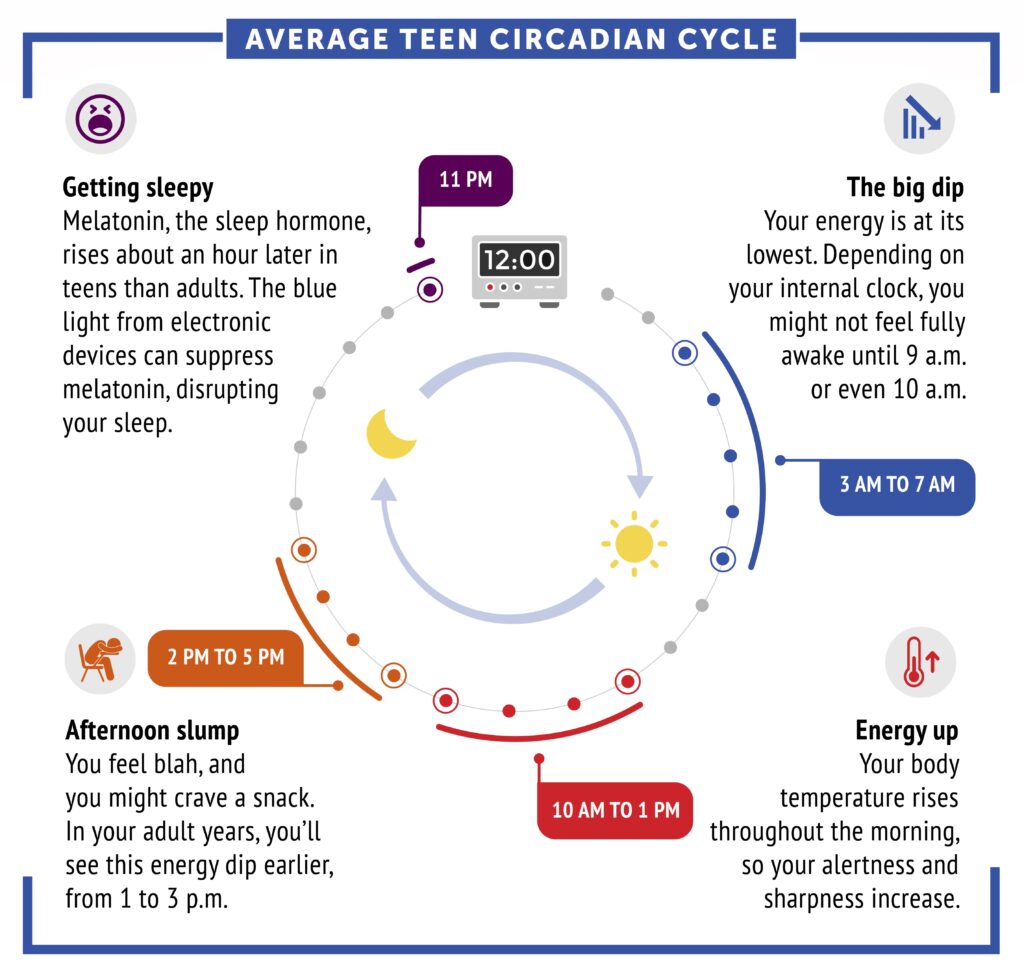

Our bodies have their own internal clocks that let us know when it’s time to go to sleep and wake up. This internal clock regulates our circadian rhythm – the physical, mental, and behavioural changes that we experience each day as we go through our sleep/wake cycle. Our internal clocks are set by many different factors. These include external cues, such as sunlight, and internal factors, such as genes that regulate the fluctuation in hormone levels in our bodies throughout the day. Research has shown that internal clocks vary between people of all ages, but they also shift as we age. When we’re teens, our minds and bodies get tired later in the day and want to sleep later into the morning. On average, teens start to enter sleep mode around 11 pm and aren’t fully alert until about 10 am. Adults, on the other hand, start to get sleepy about an hour earlier and do not require as much sleep per night as teens.

Teens’ circadian rhythms – the factors that control the sleep/wake cycle – are shifted compared to other age groups, causing them to get sleepy later at night and become alert later in the morning. Image: NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences, CC-NC-SA 3.0.

Does school start too early for teens?

As most teens will tell you, the world does not operate on their schedule. The average school start time in Canada is 8:30 am, and in the US it’s 7:45 am. This means that adolescents and teens aren’t getting enough sleep each night. And the solution is not as simple as making teens go to bed earlier. According to Dr. Jean-Phillipe Chaput, professor in the School of Epidemiology and Public Health at the University of Ottawa, and researcher at the CHEO Research Institute’s Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group, “If you don’t feel tired, you’re not going to sleep. So even if teens go to bed at 9:30, that’s not going to translate into getting more sleep.”

Why does this matter? According to Dr. Chaput and other sleep researchers, a chronic lack of sleep is associated with many negative outcomes, including increased risk of obesity, type two diabetes, depression, and lower grades. The evidence has persuaded organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics to formally recommend that schools delay start times for teens.

While it’s difficult to demonstrate that a lack of sleep directly causes any of these complex problems in teens, Dr. Chaput’s research has shown that the amount of rest teens get at night impacts a key risk factor for type 2 diabetes.

For example, Dr. Chaput co-authored a study that showed that sleep deprivation is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity in adolescent boys. Reduced insulin sensitivity, also known as insulin resistance, is often a precursor to type 2 diabetes. More recently, Dr. Chaput has looked at the impact of “prescribing” 1.5 hours of additional sleep for teens with increased risk for type 2 diabetes. The study used smartwatches to measure the amount of sleep the teens got each night.

“With the 1.5-hour prescription, they slept 1 hour more. And then we saw a huge improvement in insulin sensitivity,” says Dr. Chaput.

Why can’t we just let teens sleep in?

There are numerous barriers to delaying school start times, including the cost and logistics of bussing students to school. Image: Kelly, CC0.

While some school districts are experimenting with later school start times for teens, Dr. Chaput says he’s not seeing a widespread change. “As a scientist, I’m looking at health. When we talk about high school start times, now you’re mixing health with politics, and that’s the main challenge.”

There are multiple barriers to delaying school start times, including the cost and logistics of bussing kids to school, and the impact on parents and teachers, who are operating on adult sleep schedules.

“It’s always easier not to change things in life, because every change has some side effects,” says Dr. Chaput.

What else can we do to help teens get more rest?

If we can’t shift school start times to better fit teens’ circadian rhythms, how can we help teens get more, or at least better-quality, sleep? Dr. Chaput argues that fostering a healthier approach to sleep is about more than just what time teens need to wake up. Promoting other good behaviours, such as reducing screen time before bed and increasing physical activity during the day can help everyone improve their sleep patterns.

“We need to think more as a whole, as opposed to just fixing one thing, thinking that is going to solve the rest,” says Dr. Chaput.

In addition to taking a multifaceted approach to improving sleep, Dr. Chaput would like to see sleep researchers focus more on the impact of behaviour on sleep and how we can shift people’s perceptions of the value of sleep.

“I think we need to find a good way to better value the importance of a good night’s sleep for health as opposed to seeing it as a waste of time,” says Dr. Chaput.

We’ve all had the experience of trying to power through a day without enough sleep. We don’t need researchers to tell us that sleep deprivation is hard on our minds and bodies. But research like Dr. Chaput’s could help us understand exactly how it harms us, and how we can change our sleep behaviours to improve our health, particularly during important developmental stages like adolescence.

Feature image: Teens’ internal clocks are on a different schedule than adults’, and there are negative health consequences to making them live according to adult schedules. Image: Black Ice, CC0.